Jews’ Role Murky As Rebel Banner Drops in Georgia

ATLANTA — Thanks to a last-second compromise reached by lawmakers last week, the state flag of Georgia is about to drop the notorious Confederate battle emblem for the first time in nearly 50 years..

The deal — widely seen as a rebuke of Republican Governor Sonny Perdue — came quickly, catching most observers by surprise. But for Tyrone Brooks and other black state legislators, it has been a long fight to remove the Confederate emblem — the Rebel Cross — from the flag.

Some black leaders have questioned why the Jewish community has not taken a more public stand in that fight, but Jewish leaders said they were working “behind the scenes” on the issue.

More than two decades ago, Brooks helped lead the initial charge against the Confederate emblem, which has dominated the state flag since 1956. The flag was adopted by the state legislature

that year as a defiant response to the Supreme Court’s landmark decision outlawing segregated public schools, and went largely unchallenged for the next three decades.

In 1981, then-Alabama governor George Wallace ordered the Confederate flag raised in the state capital. When black legislators made a symbolic attempt to tear it down, police arrested them. The episode inspired a drive by black leaders in other Southern states to remove the Confederate battle emblem from their states’ symbols.

From South Carolina to Mississippi to Georgia, a new Civil War of sorts was beginning. And, in the eyes of some, Brooks was the enemy.

Soon after the flag controversy began two decades ago, an Atlanta television reporter showed Brooks a tape of Ku Klux Klan members burning a black doll with an afro and his name written on it.

“You could hear them on the tape,” Brooks recalled in an interview with the Forward. “They said, ‘We cannot get our hands on that nigger. But if we ever do get our hands on him this is what we are going to do to him. We will burn him in effigy tonight but one day we will get him in person.’ Then I saw some of the faces on tape. Some of those Klansman pulled their hoods up. I see those same faces walking around the Georgia capital all the time.”

Brooks and his fellow black legislators made little headway in their battle against the Confederate battle emblem until 2001, when then-governor Roy Barnes pushed through legislation giving the offensive symbol a smaller place on the flag. The new version included a band of miniature versions of all the previous state flags, including the controversial 1956 flag with the Rebel Cross.

Some residents who favored the 1956 flag were angry that the issue had not been put to a referendum or at least given greater public airing. At the same time, polls showed only 13% of Georgians still endorsed the flag featuring the battle emblem.

Speaking of the minority dedicated to keeping the old flag, Brooks said: “Some of these people are true lovers of history. Others are racist demagogues, Klansmen, Neo-Nazis and skinheads who call themselves Sons of the Confederacy in the daytime but at night, I promise you, they are out somewhere burning crosses and talking about people of color.”

In the 2002 gubernatorial election, Republican nominee Sonny Perdue made the Confederate flag a lynchpin during his surprisingly successful campaign. Perdue promised voters a referendum on whether the 1956 flag should be brought back. The promise helped win him the backing of supporters of the Confederate battle flag, who worked to deliver his upset victory.

But legislators from both sides of the aisle fought hard in recent weeks to head off any effort to bring back the 1956 flag. In a last-second deal that caught Perdue off guard, lawmakers agreed to a new state flag based on the first national flag of the Confederacy, which had three broad bars and a circle of stars in the corner. The new flag, which is almost identical to one Brooks had pushed for at the start of his campaign, will include the words “In God We Trust.” The motto has never appeared on any of state’s previous flags.

Brooks said that blacks could accept the national flag of the Confederacy, because it simply reflects a historical time period, while the better-known battle flag symbolizes the armed struggle to preserve slavery. Many critics of the 1956 flag, which is based on the battle flag, say it bears the additional burden of recalling efforts to resist desegregation.

Assuming Perdue signs the bill — aides say he will do so next week — the new flag is expected to go up in about a month.

Under the compromise bill, first floated by one of the legislature’s most conservative Republicans, Marietta Representative Bobby Franklin, voters will choose in March 2004 between the new flag and the multi-symbol flag raised by Barnes. To help win support from Perdue, the assembly is meeting his request for new tobacco taxes, though less than half of what he wanted.

In the end, observers said, Perdue came out the political loser: He failed to satisfy constituents who wanted a referendum on the 1956 flag, in exchange for a half measure that is unlikely to win him any additional support.

What’s not as clear, it seems, is the role played by the Jewish community in the debate. During recent months, some black leaders have observed that the Jewish community generally stayed on the sidelines.

But Judy Marx, associate director of the American Jewish Committee’s Atlanta chapter, said her group was working against any efforts to bring back the 1956 flag.

“We fought hard behind the scenes,” Marx said. “We wrote every state legislator making our opinion known, but we were not out in front in the media.”

AJCommittee helped create the local Black-Jewish Coalition in 1982 and underwrites Project Understanding, a retreat for black and Jewish leaders.

Neil Falis, an attorney with the powerhouse Atlanta law firm Kilpatrick Stockton, said that during a Project Understanding retreat last year, he realized how upset many black leaders were about the apparent silence in the Jewish community.

“The first question asked of me at the retreat,” Falis recalled, “was ‘Why are Jewish leaders not helping us out and speaking out on the flag issue?’”

Falis responded by saying that he felt the flag was just as offensive as the Nazi swastika.

That comparison was rejected by Rabbi Ilan Feldman, religious leader of Congregation Beth Jacob, an Orthodox synagogue.

“I understand the emotional comparison, but historically the Confederate flag is not to slavery what the swastika is to the murder of Jews,” Feldman said.

“The Confederate symbol was not developed specifically to express a philosophy,” Feldman said. “It happened to be the symbol of the States of Confederacy. It is not an expression specifically of slave heritage. The swastika was developed specifically for the Nazi philosophy and was designed specifically to express that point of view. I think reasonable people can disagree on the meaning of the flag, but I am certainly sympathetic to those who feel it is offensive. However, we are not morally obligated to agree this flag stands for racism.”

But Rabbi Mark Kunis, religious leader of Traditional Congregation Shaarei Shamayim, rejected this view of the flag.

“The Confederate flag is a racist flag,” said Kunis, whose synagogue is just a few minutes away from Feldman’s. “It is a valid comparison. It stirs up racial memories that are difficult, painful and offensive. Every single Jew I speak to feels strongly about this issue — having a flag that is offensive to its constituents is abusive and intolerable. It is crazy to contemplate bringing back the Confederate battle flag.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

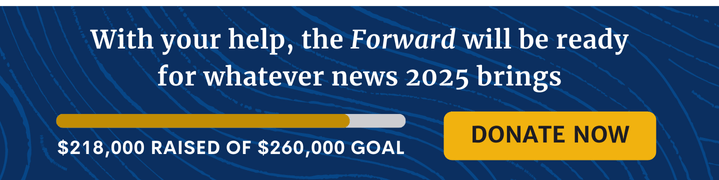

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO