Secrets of the City

In Chapter 56, Leonid stumbled upon a possible path to legitimacy over a clandestine burger with Brooke.

* * *|

The papers were dripping with Schadenfreude. The fall of Neil Maguire was the lead editorial in all of the papers, even the local Arabic-language paper, which a translator had kindly placed in the pile that spread across the Mayor’s conference table.

There was a picture from the funeral of the widow holding her daughters’ hands. There was the car photographed again and again with Neil’s arm hanging oddly at his side. There was Daquinne’s statement that she had been sexually harassed by Maguire and forced into acts she found abhorrent. Her lawyer was threatening to sue the city.

There was a protest in front of the Parking Department by scofflaws who wanted a general amnesty. There was a cartoon of Mel, his sad eyes sadder than ever, saying, “Good night, Sweet Prince” over Neil Maguire’s yacht, which was pictured sinking in the water.

“I could,” Mel told his assembled aides, “issue a statement: ‘I am not a crook.’” His aides stared at him stony-faced. “That’s a joke,” he said. His press officer moaned. “One rotten apple turned up. So what? We stay cool.”

“Right now what we need is a political move, a popular political move to divert attention,” said Mel’s former campaign manager, Moe Alter, now consultant No 1. Moe raised his coffee to his lips. It went down the wrong pipe, and he choked and spit coffee across the table. “Nice,” said Mel. “Sorry,” said Moe. “What would you suggest?” Mel asked.

Harold, who had entered bearing paper towels, began to wipe the table. “How about you hold a gay ball in City Hall, a municipal costume ball, come as you dream you are? That would be daring and diverting.”

“I’ll think about it,” said Mel. The Mayor wondered whether, if he came as Napoleon, the press would catch the irony or think he was delusional. In a flash of a synapse’s wink he nixed the Napoleon costume, and before the next neuron could spark, he made sure that there would not be a gay ball.

“You could,” the Mayor’s young assistant said to the head of the Department of Finance, “declare a tax amnesty for a year.” “Sure,” said Mel, “and the entire administration could take to riding the subways with paper cups in hand and signs about our necks that say, ‘City needs help, has HIV, homeless, hungry, and in debt.’”

“Maybe not,” the young assistant said as he blushed. “Let’s have a massive firing,” said the press officer, “a clean sweep of the ranks, a sign to the public that we won’t put up with any wrongdoing.”

“But who’s done wrong?” asked Mel. “Only tyrants fire people for no reason.” “It would look good,” said the press officer. “But it wouldn’t be good,” said Mel, thinking that perhaps he should fire the press officer. He held that thought for another time.

Mel stood up. He had had enough advice. “Moe, stay. Everyone else, leave. I am going talk to the people of the city on the radio this afternoon. Arrange it,” he said. “Now!”

The crowd left. Moe, who was a heavy man with a fondness for ties with animals on them, a man who had been around the block and had enjoyed the walk, said, “Let’s sit down and do it.”

“This better be good,” Ruth said when she found out about the radio address. “Break a leg,” Jacob said over the phone. “I’m not an actor,” his father grumbled. “You’d better be,” said Jacob.

“Don’t worry, Daddy,” Ina said when she called. “I know you’re a great mayor.” “Thank you sweetheart,” said Mel. Of course Hitler’s daughter, if he had had one, would have cooed at her Daddy, too. A daughter’s love is hardly proof of more than paternity.

He walked into the studio, Moe at his side, Harold holding his coat, four police at the door.

He put on the headphones, heard Daisy Bartlett, who ordinarily led the popular 4 o’clock call-in show about gripes and grievances, announce that her program would be interrupted by words from the Mayor, words of importance to all the citizens of the city.

He began: “I want to tell you about Neil Maguire. He was my friend, my good friend. He knew how to make me laugh. He knew how to stand at my side. He was a caring man who loved his family, and I remember how he brought me a pot of his mother’s meatballs when I was studying to pass the bar. I know that whatever he did and whatever happened in recent years, to his sense of honor and decency, it was once the envy of everyone who knew him.”

“He was a good man,” Mel continued, “who let himself down and let me down. I’m angry at him about that. But I will miss him, and so will his family, and so will this city in which his presence was an addition, his unique human soul a source of light like all our souls.”

The Mayor took a sip of water. “Let the ghouls who are dancing on his grave slink back into the shadows. In this world there is so much to tempt a man — that is not meant to excuse, but to explain why I grieve for Neil Maguire. He was my friend, and I will never take my friendship back.”

The Mayor paused briefly. “And now let me talk about this city, our city. These are tight times when money is scarce. We cannot build new parks or public theaters or even furnish our hospitals with the newest machines or hire enough nurses. I can barely afford to fix the potholes that’ll appear as the snow melts. I can barely get the rust off the steel cables on our bridges. We could raise taxes on the rich, but the rich bring us income. If they leave, they leave us deeper in debt. I am not Robin Hood — he was a sweet fellow but no economist.”

“My friends,” he continued, “what I can do is look for opportunities in the cracks. What I can do is hold high our spirits and remind everyone that this city, made up of so many refugees, immigrants — our taxi drivers wear turbans or pray at mosques; our grocers speak Korean, and our Chinatown has the best dumplings in America — this city remains the hope of the future, a metaphor for the world as it could be. We don’t kill each other, not in large numbers. We work together, side by side; we ride the subways and buses, side by side. In the end, we will care for our sick, our elderly and our poor, and maybe we will have more jobs and have more resources in the coming years. We will believe in ourselves, our imperfect but inventive selves. We rush to catch the train. We rush to work. We rush to the movies, to the theater. We go to museums, picnic in the park, ride the carrousel. We bear children, bury our dead, are brave in the face of our own frailty. Some of us are too sad, sadder than anyone should have to be, and some of us are too greedy and selfish and cruel. So we have always been. What a wonderful noise we make each day. We live in a great city that is great because we live in it.”

With that, Mel Rosenberg said thank-you to his listeners and went home.

Next week: Leonid locates his lucky star.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

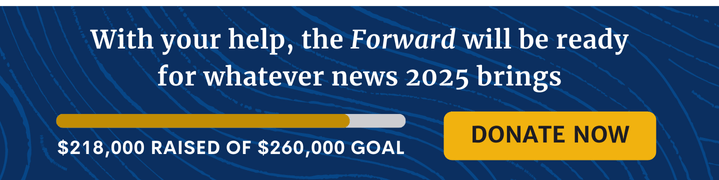

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO