Discrimination in the Genes

The Senate took a historic step forward this week toward protecting patients’ rights and advancing medical research, with its 95 to 0 vote to ban genetic discrimination in employment and insurance coverage. The measure, which still requires House approval, had been stalled for eight years, deadlocked between patients’ rights activists and scientists on one side and insurance industry lobbyists on the other.

The deadlock has deterred countless Americans — tens of thousands by some estimates — from obtaining potentially life-saving genetic tests for fear of losing jobs or insurance should their records become public. It has also slowed research in one of the most promising fields of medical science by scaring away volunteer subjects.

Credit for ending the deadlock belongs to a bipartisan group of lawmakers, led by Republican Olympia Snowe of Maine and Democratic leader Tom Daschle of South Dakota. Credit is due, too, to the majority leader, Tennessee Republican Bill Frist, a physician who saw the bill’s importance and helped clear the way.

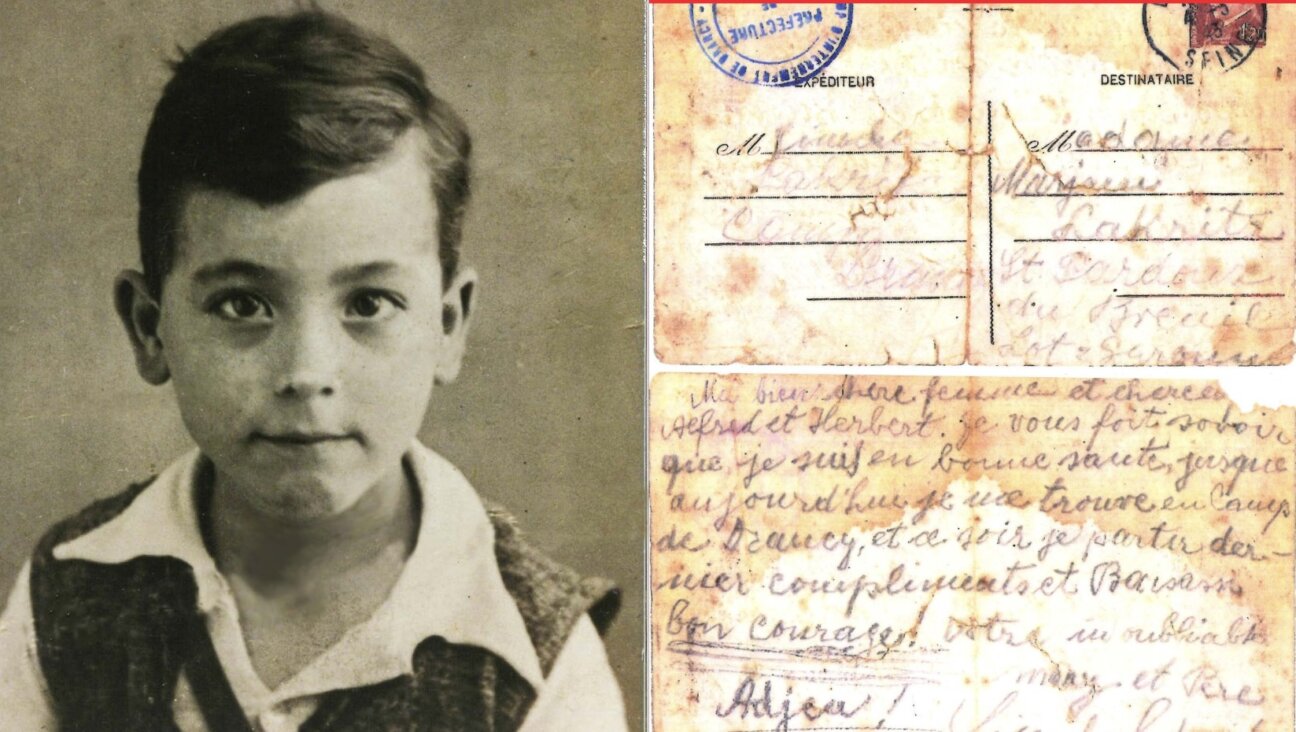

No one, however, has more right to celebrate this week than Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization, which first identified the issue in 1996 and has been pressing for action ever since. The group’s interest has been twofold, both as a medical organization and as a Jewish women’s advocacy group.

It was scientists at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem, working with the National Institutes of Health, who made the breakthrough discovery in 1995 that a genetic mutation linked to breast cancer, BRCA1, was disproportionately present among Ashkenazic Jewish women. Following up among its constituents — urging women to be tested and to volunteer for research — brought home to Hadassah the fact that women didn’t want their genetic histories known. Since then Hadassah has been one of the main advocates of the reform passed by the Senate last week.

The issue is critical to women’s health, but its implications go further. Ashkenazi Jews are of keen interest to genetic scientists as a readily identifiable group with a relatively closed gene pool. Many advances in gene research have been made possible by the availability of an educated, easy-to-recruit population with distinct genes, the result of centuries of in-marriage. Some researchers suggest that the recent rise in interfaith marriage could dilute Ashkenazic genes to the point where research is inhibited. Tellingly, that tipping point isn’t yet in sight. Research continues.

The latest breakthrough was published just this week in The Journal of the American Medical Association, pointing to a genetic variation that may boost longevity by producing oversized cholesterol particles. The oversized cholesterol, it seems, is less likely to stick to arteries and clog them up. There’s some indication that the life-extending gene is more common among Ashkenazi Jews, but everyone seems likely to benefit.

There is, of course, a downside to the closed Ashkenazic genetic history. Inbreeding has left this community vulnerable to a list of specialized diseases, as readers of the Forward’s annual Genetics supplement know all too well. The heartbreak of these deadly diseases only adds to the urgency, both of testing families for the gene markers and of pushing ahead to find the cures.

All those factors only underline the necessity of the life-saving legislation approved by the Senate this week. But the measure isn’t law yet; it still has to get through the House, where lobbyists may yet derail it. What’s needed now is firm leadership from the White House, to make clear that delays won’t be tolerated.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO