Judging Friedman

Milton Friedman, the economist who died last week at age 94, was an intellectual giant of the 20th century, one of a tiny group of social theorists whose ideas could be said to define an era. Champion of free-market economics, fierce opponent of government intervention, he was responsible, more than any other individual, for the ideological underpinnings of today’s world economy. So vast was his influence, so piercing his intellect, that even those who disagreed bitterly with his ideas acknowledged him as a giant.

Born in Brooklyn, educated at Rutgers and at the University of Chicago, Friedman worked as a government economist during Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal before returning to academia after World War II. He taught at the University of Chicago for three decades, researching economic models and mentoring the group of conservative economists who came to be known as the Chicago School. Rejecting the interventionist government-spending ideas of John Maynard Keynes, whose theories dominated economics at mid-century, Friedman taught a purist capitalism in which economies thrived best when left alone; indeed, he taught, political freedom itself could thrive only amid free markets. The only proper role of government in the economy, he taught, was control of the money supply.

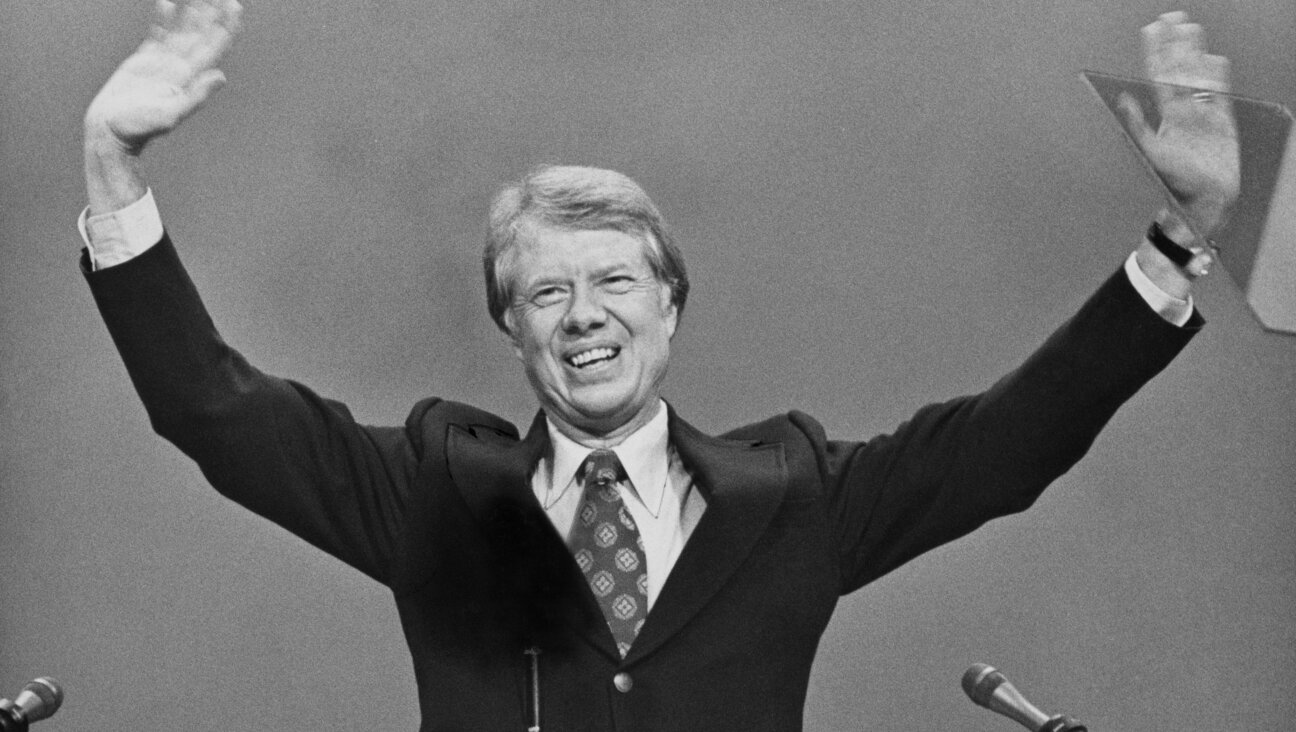

His monetarist theories won him the Nobel Prize in economics in 1976, but his influence was just beginning. His ideas dominated the late 1970s, 1980s and beyond, adopted with ferocious enthusiasm by Margaret Thatcher in England, Ronald Reagan in America, Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel and General Augusto Pinochet in Chile, for whom Friedman served, notoriously, as an adviser.

It’s no coincidence that the names of Friedman’s most zealous practitioners have become synonymous with a heartless capitalist fundamentalism. Friedman himself was, in his scholarly way, a zealot. He took his notions of unregulated capitalism as seriously as his theories of monetarism and consumption, and by the force of his eloquence and personality he spawned a movement of followers as ideologically driven as he was.

Friedman’s legacy includes some of the basic understandings that drive economic growth around the globe today, from free-market America to social-democratic Europe to Communist China. But that same legacy also includes a deregulated atmosphere that has spawned a weakened welfare state, a wave of corporate greed and skyrocketing social inequality within and between nations. The final balance sheet has yet to be tallied. Friedman may hear the tally soon; the rest of us must await the verdict of history.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO