Ravensbruck’s Famous Survivor

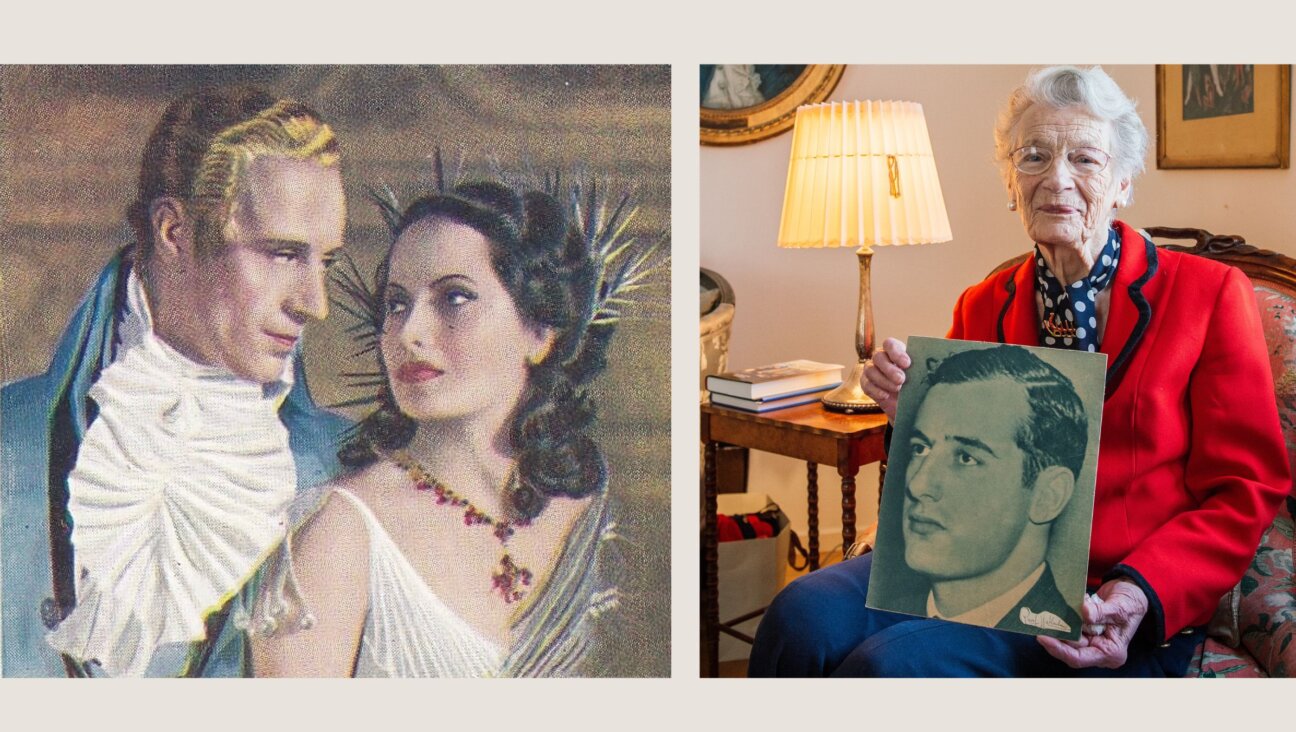

Fiorello’s Sister: Gemma La Guardia Gluck’s Story

Edited by Rochelle G. Saidel

By Gemma La Guardia Gluck

Syracuse University Press, 184 pages, $16.95.

Back in the 1980s, a number of Holocaust scholars and “people who should know better” told historian Rochelle Saidel that Ravensbrück, a women’s concentration camp located about 60 miles north of Berlin, was used for political prisoners and that “there wasn’t a Jewish story there.” Saidel proved them wrong by writing what many consider to be the definitive book on the estimated 20,000 Jewish prisoners that passed through the camp.

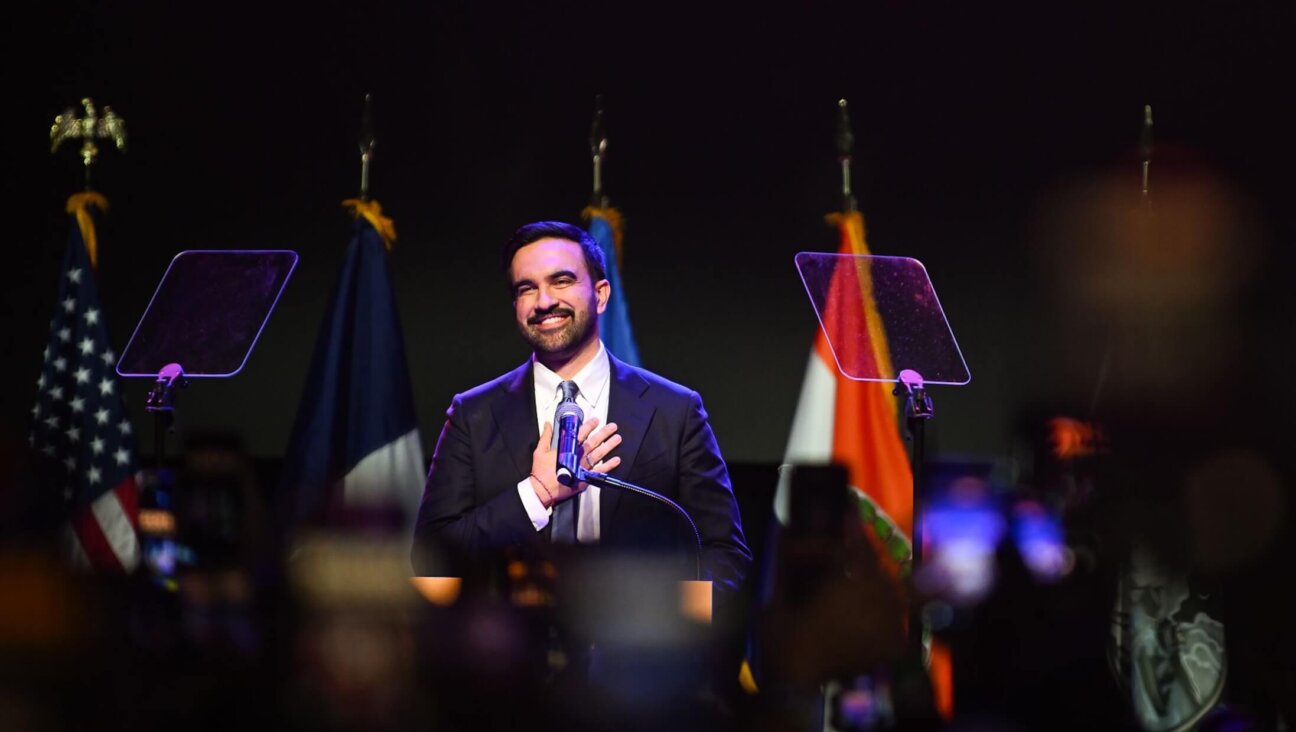

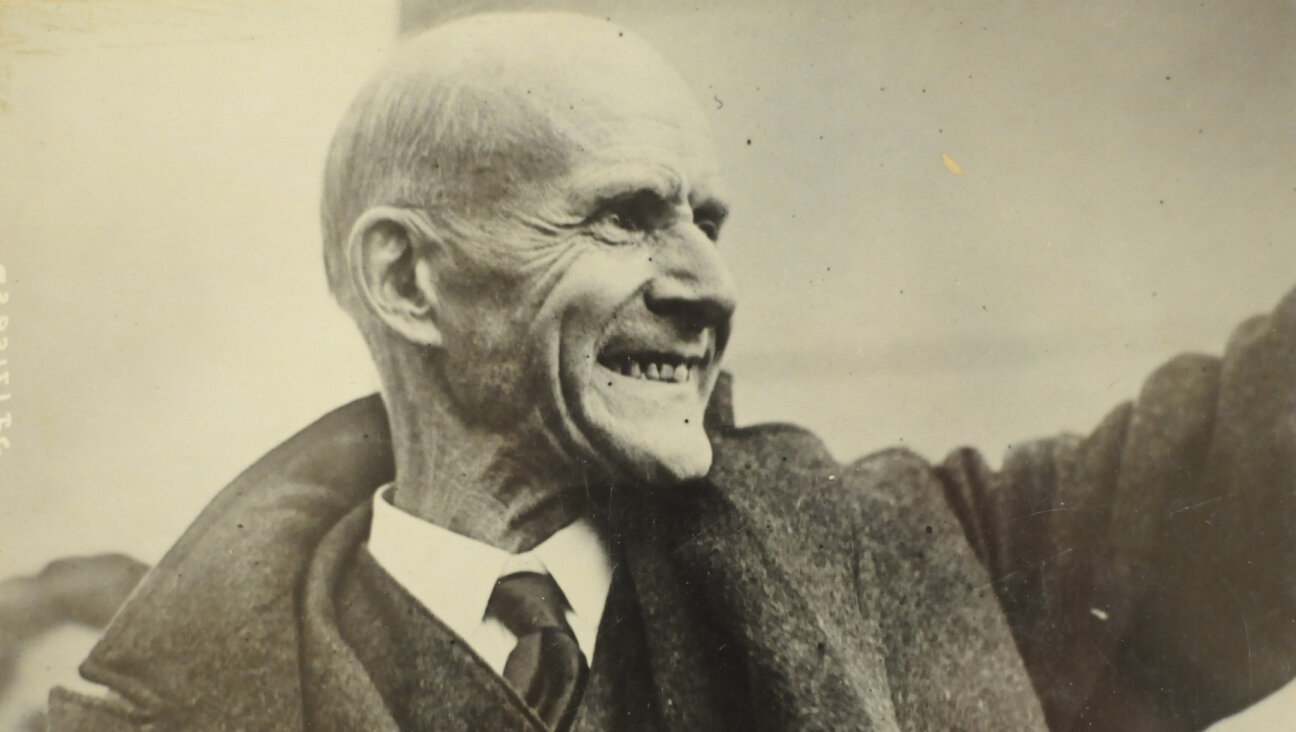

Among them was one prisoner, the camp’s most famous survivor, whose story struck a particular chord with Saidel: Gemma La Guardia Gluck, sister of legendary New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Now, with Saidel’s help, Gluck’s memoir — first published in 1961 — is being re-released by Syracuse University Press under the title “Fiorello’s Sister: Gemma La Guardia Gluck’s Story.”

Born in New York to an Italian Jewish mother and a “lapsed Catholic” father, Gluck and her famous brother grew up in the United States. During their childhood, though, they joined their parents on trips back to Trieste, Italy, where their mother’s family had deep Jewish roots. In 1900, with the children grown into young adults, the family moved back to Italy. Fiorello returned to New York to attend law school, after which he ran for a number of elected offices. Gemma stayed in Europe with her mother and taught English in Trieste, where she ended up marrying one of her students and, eventually, getting caught in the maw of World War II.

Gluck was 64 when she was released from Ravensbrück in the spring of 1945. Saidel is 65.

“I think that is part of why I feel a great affinity for her now,” said Saidel in an interview with the Forward. “At my age, I can’t stand for a very long time in a museum and look at a painting without my leg hurting. And then you read that they’re standing there for five hours in an appel,” she said, referring to the concentration camp roll call.

During her eight months in Ravensbrück, Gluck endured a diet of turnips cooked in potato peelings. She promised herself that if she survived, she would tell the world about the camp. So Gluck resolved to observe life in Ravensbrück as best she could. She remembered the stench of the crematory, and prisoners who looked like “walking skeletons.” She remembered the babies who suffocated because they were crammed five or six to a crib, and she remembered the Polish woman housed on the “Rabbit Block” who had limbs amputated by Nazi doctors in “experiments.”

Although the Nazis considered Gluck to be Jewish, she did not think of herself as a Jew — despite the fact that her maternal grandmother was a member of the Luzzattos, a prominent Italian Jewish family active in the Italian unification effort and the rabbinical college in Padua. In her memoir, Gluck mentions a woman in Ravensbrück who begged to take off the yellow patch labeling her as a Jew, arguing that she may have been married to a Jew but she herself was not Jewish. Gluck was angered by the inmate’s plea, declaring in her memoir, “I have been married for thirty-six years to such a good Jewish husband, I am proud to wear their sign.”

In April 1945, Gluck was reunited with her daughter and grandson, who were also imprisoned at Ravensbrück. There, she had lost 44 pounds in less than a year. Her toddler grandson looked so weak, she thought, “Where am I going to bury this baby?”

The three were released in Berlin, just prior to its liberation by the Russians. Gluck writes in her memoir that the Soviets were “violating girls and women of all ages.” A year later, she read a newspaper article that revealed the fate of her husband, Herman, a Hungarian Jew who had perished in the Mauthausen concentration camp.

Despite the fact that she was the sister of a powerful American politician, it would be another year before Gluck, her daughter and grandson made it to New York. They arrived in May 1947, four months before her beloved Fiorello died of cancer. She spent the rest of her life in a low-income public housing project in Queens, built by the LaGuardia Administration. Gluck died in 1962, about a year after her memoir was first published.

Jon Kalish is a freelance radio and newspaper journalist based in Manhattan.