Double Trauma for ‘Hidden Children’

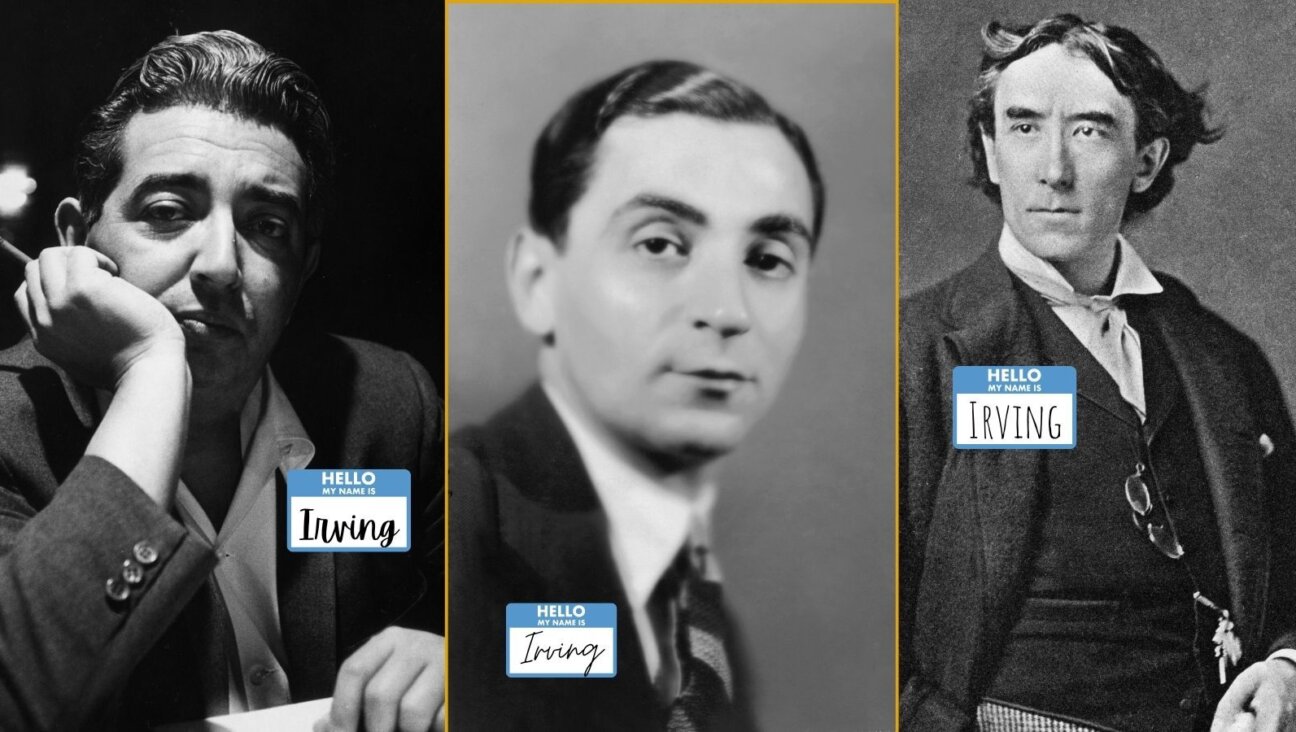

Image by forward archive

Hidden Trauma: Many Jewish children who escaped the Holocaust by being hidden as Christians discovered their true heritage later. Image by forward archive

Among adoptees for whom the discovery of a Jewish past is most wrenching are the “hidden children” — those who survived the Holocaust by posing as Christians.

In 1939, approximately 1.6 million Jewish children lived in areas that would be occupied by Nazi Germany and its allies. Although scholars differ on the numbers, it seems safe to say that between 100,000 and 500,000 of these children survived.

Read the Forward’s story ‘Raised Christian, But Jewish by Birth’

Many of these survivors were hidden children; some secreted in attics or cellars, others living in the open, with Christian families.

Joanna Michlic is director of the Families and Holocaust Project at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. She said that children who survived the Holocaust living as Christians with adopted families experienced “two massive ruptures” that affected their sense of self.

The first occurred following the separation from their biological families. Jewish parents hid their children in Christian homes or convents, where the children had to learn to conceal their identities.

The second rupture was “when the children were confronted with the news of being Jewish,” as Michlic put it, and had to leave their Christian lives behind.

Many Jewish children had been hidden as infants and, thus, had no memory of their heritage. After the war, surviving parents or relatives were eager to reclaim the children, but in many cases the children had become comfortable in Christian homes or institutions. Some were reluctant to reassume an identity that had dangerous implications for them.

Michlic’s research into the wartime biographies of Jewish children highlights stories of vulnerable young people suffering repeated traumas and dislocations — including custody battles between Jewish relatives and Christian rescuers. Even without a custody battle, many children felt significant disruption when they left the sense of security associated with their adopted parents and were sent to Jewish relatives in the United States or Palestine.

Sometimes, however, a hidden child’s reconnection to the past came as a relief.

Miriam Magall was born in 1941 and adopted soon after birth by a non-Jewish, single woman. Raised in what became West Germany, Magall was discouraged in her desire for an education and suffered sexual abuse at the hands of her mother’s male companion, a cobbler.

At 18, Magall decided to strike out on her own. She found a job in Switzerland. The night before she left, the woman who raised her revealed the truth about Magall’s past.

Magall was born in a hunting lodge in the Polish countryside to Jews hiding from the Nazis. Her mother died shortly after childbirth. Her maternal aunt convinced her father to give the infant to the woman who had been their housemaid in Warsaw. They paid the housemaid to keep the baby safe until after the war.

According to Magall, a few days after the exchange, the housemaid overheard “SS soldiers bragging that they had found a Jewish man and a Jewish woman in a hunting lodge, and they raped the woman and burned them both alive.”

Between 1963 and 1969, Magall worked in Switzerland and London and then earned a degree in languages at the University of Sarrebrucken. Magall said that it was in London, while working for a kindly Jewish family, that she “learned how to be a Jew.”

In 1969, she emigrated to Israel, where she became a successful translator and businesswoman. She married and gave birth to a son, Ya’ir, now 30. In 1988, after a divorce, she returned to Germany, where she felt the custody laws were more favorable to single mothers.

Magall now lives in Berlin, where she keeps kosher and observes the Sabbath. She published a book in German about her family, “The Bread of Affliction: The Story of a Hidden Jewish Child.” She also gives talks about Jewish life and her own story.

“Every time I talk about my murdered family,” she said, “I put another stone onto the monument of their grave.”

Gordon Haber is a frequent contributor to the Forward.