Pat Singer Is the Mother of Brighton Beach

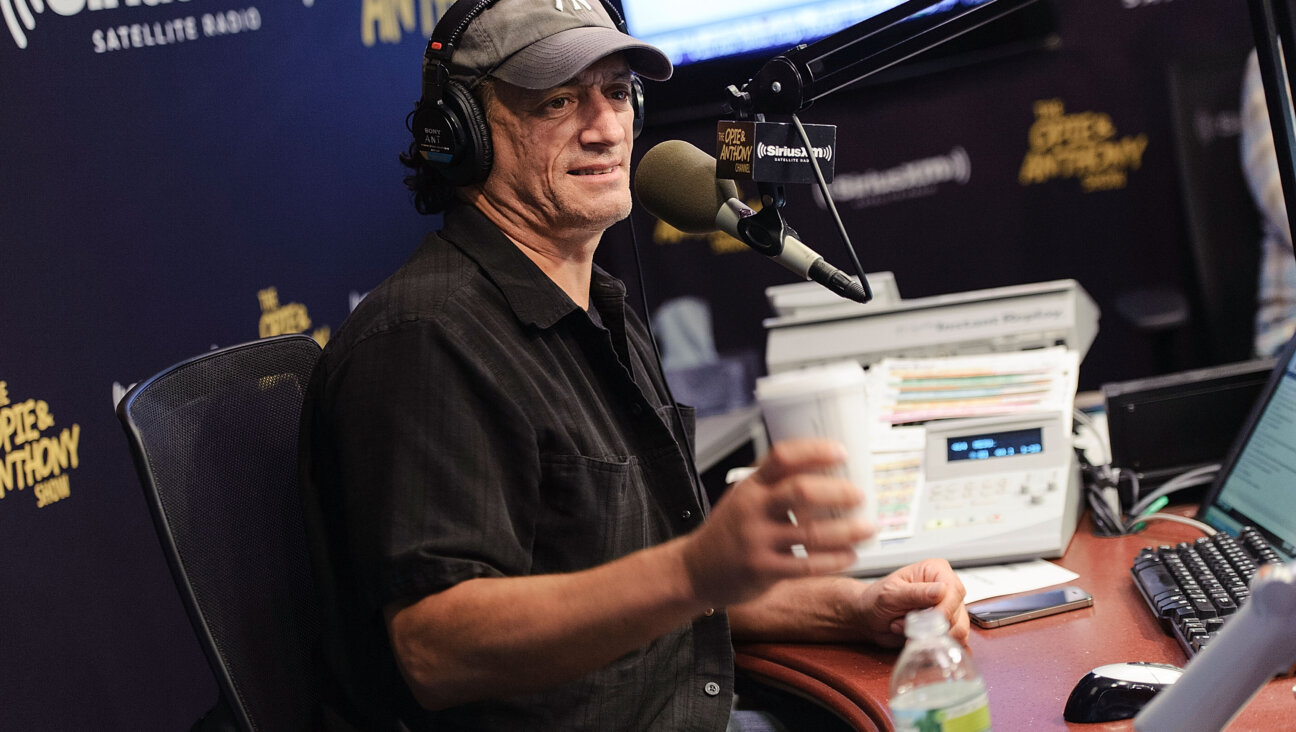

Mother Knows Best: Pat Singer, of the Brighton Neighborhood Association, has a desk filled with tchotchkes and a Rolodex filled with the names of public officials. Image by Ari Jankelowitz

Located on the main stretch of Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach Avenue, among numerous Russian delis, Russian-language bookstores and a shuttered Russian travel agency, the Brighton Neighborhood Association stands out. Its window is one of the few on the block with signs predominantly in English, and it’s one of the few storefronts near the elevated tracks of the B and Q trains that doesn’t actually sell anything.

This doesn’t stop people — and definitely not elderly Russians — from strolling through the glass front door, unannounced, on a regular basis. Some mistake the office for a thrift store and start lifting up, one by one, the porcelain and enamel elephants, gifts from friends and other tchotchkes on the desk of Pat Singer, founder and executive director of BNA, a not-for-profit social service agency in Brighton Beach, a neighborhood that stretches for one mile along the Atlantic coast.

Singer has to break into her limited knowledge of Russian to shoo them away: “Not magazin, this office! Not for sale, nooo! Get your hands off my desk!”

All photos by Ari Jankelowitz

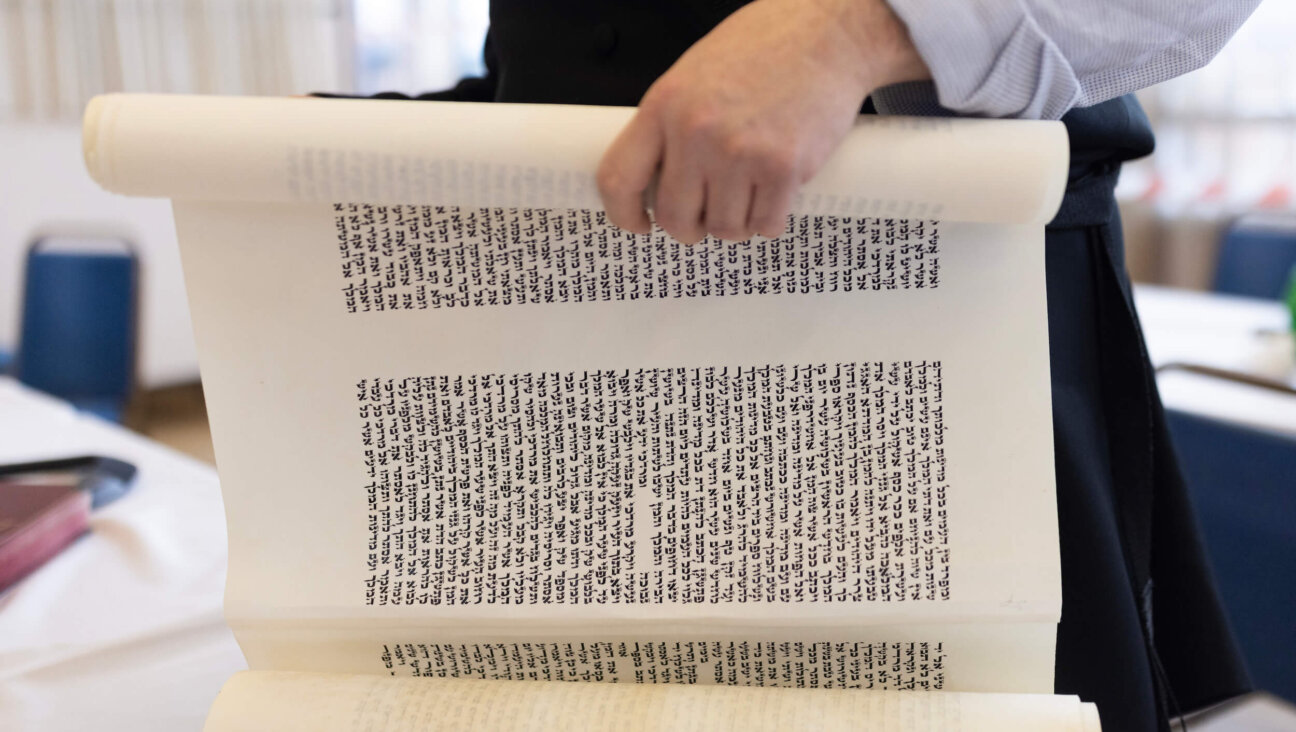

Singer, the granddaughter of Jewish immigrants from Odessa, is a community leader in this predominantly Russian-speaking neighborhood: “I’m called ‘the Mother of Brighton Beach,’ but I’m a bad mother, because I can’t communicate with my children.”

Born and raised in New York City, Singer, 73, used to take weekend trips to Brighton Beach as a teenager in the 1950s. She loved the area’s warm and sunny beaches, and began spending weeks at a time there over the summers. “People were friendly here! I liked the smells, the soft air, the bagels, the whitefish, the whole nine yards,” she said. This enclave of Jewish culture — Brighton was home to many Yiddish-speaking European Jewish immigrants and Holocaust survivors at the time — felt like a novelty and was markedly different from her experiences in Queens Village, a largely German Protestant area where Singer spent most of her childhood. There, Jews were explicitly excluded from community activities.

One year when Singer was in elementary school, she watched as all her peers prepared for an annual parade held by the local church. She was told she couldn’t participate as a Jew, but she wouldn’t let that get in her way: “I took my little sister and marched across Queens Village…. I got behind a float, and I stood there with my sister. Then this woman grabs me by the dress and my sister, and takes me into the Sunday school and says — she was my neighbor — ‘These girls aren’t Christian, they’re Jewish.’ So the reverend of the church called up my mother and said, ‘I have your daughters here.’ My mother said, ‘You know the Old Testament is the same in all religions, so let ’em march!’ And so we marched.”

This trademark stubbornness did not diminish over time. A protest organized by Singer a few decades later would firmly establish her as an outspoken leader. In 1977, Brighton Beach — the area to where she had since relocated — was succumbing to New York City’s fiscal crisis of the 1970s. Crumbling infrastructure and job losses forced middle-class families to move away, leaving abandoned buildings that were sometimes set on fire. Singer recalls one month when there were 13 muggings on her block alone.

Things reached a low point when her apartment building, where she still lives today, emptied out: “It’s a 96-unit building, so to wake up and find out that all your friends have moved to Long Island or New Jersey, it’s kind of sad!” Singer no longer recognized the idyllic community of her childhood, where she used to sleep on the beach, “cooled by the ocean breeze and unconcerned about crime.” Enough was enough.

She put up signs around the neighborhood to advertise a community meeting. Sixty people ended up attending. That weekend, Singer helped mobilize 500 or so residents for a protest against skyrocketing crime and a lack of police protection. Senior citizens — many carrying canes and walkers, others in wheelchairs — blocked traffic at the neighborhood’s main intersection for four hours. “We had the funniest little circle…. We were out there like crazy people.”

Singer, at that point divorced with two teenage children, was decades younger than many of her fellow concerned citizens. But with her bright-red cropped hair and her round, energetic face, she was the movement’s figurehead. (Nearly 36 years later, she looks the same.)

After she successfully convinced local police commissioners to patrol the area more frequently, a group of community members started meeting regularly at her apartment. Two years later, State Assembly member Chuck Schumer (now a senior New York State Senator) gave her a grant of $25,000 to open an office. And so the BNA was born.

In the association’s early years, Singer pursued negligent landlords, encouraged voter registration and lobbied for the city to repair broken streetlights and potholes. As she became more established she sometimes advocated for commercial development to renew her neighborhood and took positions that appeared to favor developers, which ruffled some feathers. State Assembly member Alec Brook-Krasny, the first Soviet-born elected official in the United States, who represents Coney Island and Brighton Beach, says that not only did some people take odds with her positions, but they also didn’t like her style: “When she agrees with something, she is very loud, and you can hear her voice and her opinion everywhere. Some people might not like that, but I respect it.”

The neighborhood changed drastically when some 25,000 Soviet exiles moved there between 1977 and 1980 because of temporarily relaxed immigration policies in the USSR. Singer recalls walking through the neighborhood and hearing a new language: “What the hell is this? They were rude and pushy in the grocery stores, grabbing for toilet paper, not realizing it would still be there tomorrow.” It was hard to reach out to the growing Russian-speaking community; life in the Soviet Union made the people paranoid and suspicious. But when Singer successfully fought for the local precinct to hire Russian-speaking police for a more culturally competent force, her work started to achieve recognition.

This influx of Russians actually helped BNA turn the neighborhood around. New immigrants bought up empty apartments and cheap housing and started to populate vacant storefronts with Russian-speaking businesses; however, it wasn’t a smooth transition. Shootings in mafia-operated nightclubs led some fearful residents to move to nearby Sheepshead Bay.

The 1990s brought renewed prosperity. Singer fondly recalls the period, even though many older residents clashed with the newly arrived: “They weren’t used to young kids screaming and carrying on, fighting, slamming doors, throwing vodka bottles in the incinerator and all that. But it’s called life! Life was returning to Brighton Beach.”

And now, some of Singer’s fans are the Russians who came to trust her. They are not necessarily involved in local politics, but they rely on social programs like welfare, Section 8 housing and senior community centers. Singer helps them understand, access and maintain these benefits.

This is how Singer came to represent Brighton Beach even though she does not share the language or background of the majority of her constituents. Walking around in winter, one encounters women in their best furs and mink caps with wide flaps covering each ear; street vendors, in black shawls, hunched over, selling freshly baked piroshki; old men playing chess on the boardwalk, or local Chabad members offering their pamphlets to Jewish-looking passersby. Despite recent influxes of Central Asians, Middle Easterners and Latinos, almost 80% of Singer’s neighbors are Russian-speaking immigrants, and nearly 40% are not proficient in English. Singer says she sometimes feels like the “token American” — ironic, considering she moved to the area because of a sense of finally fitting in.

Singer, though, is cheery, raw, honest and often self-effacing. She’s also quirky: Her office is decorated with plaques that read “51% Sweetheart, 49% Bitch, All Woman,” “Stop Kvetching,” “Wonder Woman Works Here,” and “Redheads Are Sexier.” If people stop by anytime during business hours, they are guaranteed to see her sitting at her dark wood wrap-around desk, surrounded by her overstuffed Rolodex, a phone, a typewriter, a computer and stacks of paper. (She’s only taken one vacation in the past 30 years. Even when Singer was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2001, which she has since beaten, she never took a sick day.)

Today, Singer is addressing the issues that plague an aging community. One time, a man came into her office and collapsed. Singer called a car service to take him to the hospital, and it turned out that he needed a pacemaker. He had no remaining family, so she’s since helped him relocate to a nursing home and she even dragged his furniture out of his apartment herself.

Singer is aging along with the very population she serves: “Tomorrow I could be the ‘I’ve fallen and I can’t get up’ person!” She laughs a self-deprecating chuckle, which belies the stresses and traumas she’s experienced. In 2001, a flood devastated the BNA office and much of its equipment. Then there was Hurricane Sandy in 2012. I was lucky to get a tour before Sandy struck, when she showed me the years of BNA’s life charted haphazardly on her cluttered walls. Singer breezed over articles called “This and That With Pat,” “Special Honorees Make Brighton Neighborhood Life Grand” and “Singing the Praises of BNA Founder.”

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Sandy — when homes and businesses in Brighton Beach were flooded and badly damaged; when the smell of leaking gas crept through the streets, and pounds of sand from the beach lay on sidewalks — Singer worked in the dark without heat, using her cell phone to help those stranded in buildings without working elevators. Recently, she temporarily lost government funding and had to lay off her part-time staff, the bilingual outreach workers who connect her to the newer immigrant groups. Still, she persists.

Some elevators in buildings with high elderly populations are still not working, even months after the storm as landlords wait for help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency or insurance money. Singer has been posting daily updates written in capital letters on Facebook about the status of these repairs, shaming delinquent landlords. It’s actions like these that make her friends and colleagues note her tireless dedication. State Assembly member Steven Cymbrowitz remembers her walking through vacant and dilapidated buildings in the 1970s with the same fiery determination that she has now: “She shows no fear,” he says.

And she shows no sign of letting up or retiring. Each day brings something new. Maybe she’ll explain Section 8 housing waiting lists to a crying Russian who can’t afford to live in the area anymore. Maybe she’ll stuff goodie bags for the annual senior Christmas party. Maybe she’ll gossip over the phone and watch TV.

What she originally saw as a duty to fight drugs and crime has now shifted. “Now I deal with leaky faucets.” I asked her once if she felt like she’d made a difference, and she said: “My only regret is not taking out a pension plan 30 years ago. I love what I do and that’s the end of it.”

Tanya Paperny is a writer, editor and translator. Her work has appeared in The Millions, The Literary Review and Campus Progress. Visit her at tpaperny.com.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO