When a Jewish Day School Closes Days Before Start of Classes

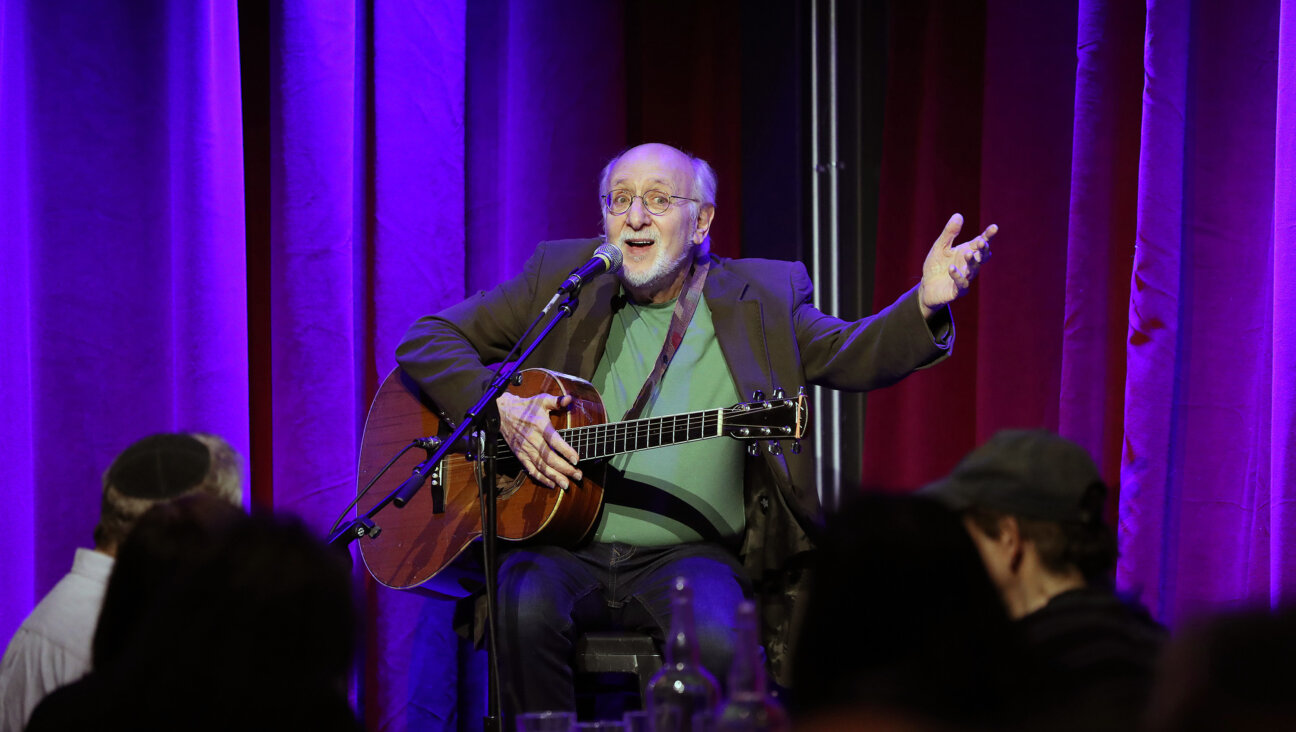

Open and Shut: Seven-year-old Lucas Ludvig, left, and his friend Elan Ronen were forced to find new schools after the Solomon Schechter School of the Raritan Valley abruptly announced it would not reopen this fall. Image by courtesy of karen e.h. skinazi

Three years ago I was living in Western Canada, and my oldest boy was a kindergartener at a Jewish day school there. The school was fine — neither spectacular nor terrible. I sent my son there because, frankly, it was the only Jewish game in town. But in my mind, I was going to send my kids to a great Jewish day school one day, and, anticipating a move to the American Northeast, where Jews are far more numerous than in Canada’s oil country, I looked for an institution that matched all my needs — a Jewish day school that prioritized mench-iness, offered excellent academics and would provide peers from the Jewish gamut. Turns out, there was just such a place, in a prime location in Manhattan. I called it up.

“How old are your children?” I was asked. I told the head of school that my oldest son was 5 and a half; my middle son was 3 and a half; my youngest was irrelevant for the moment.

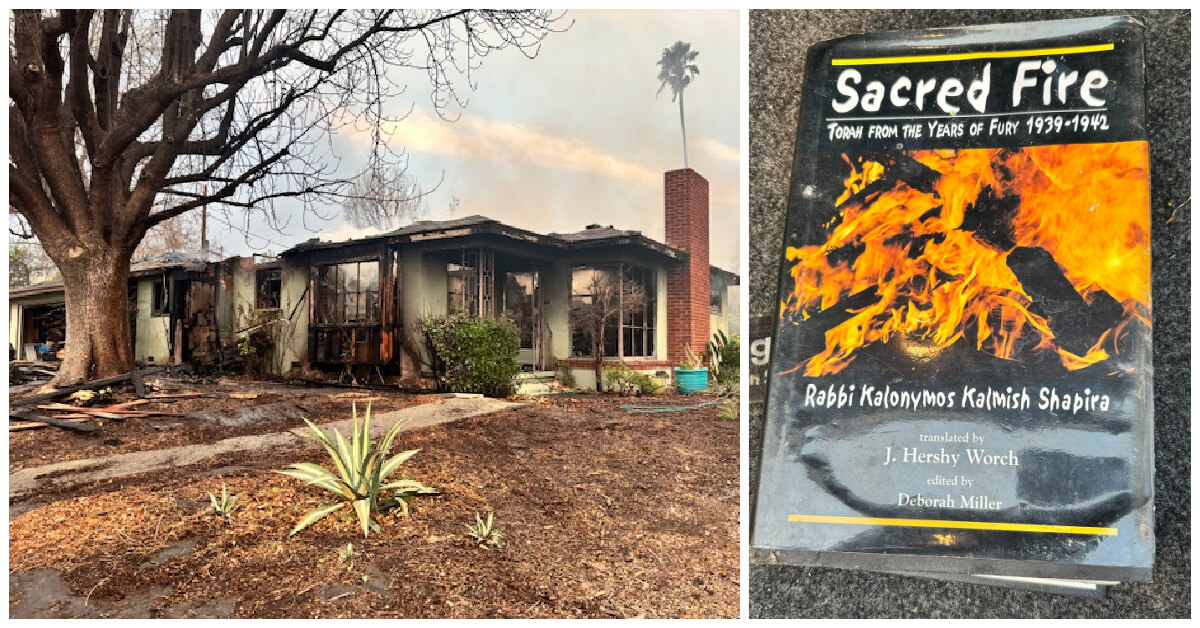

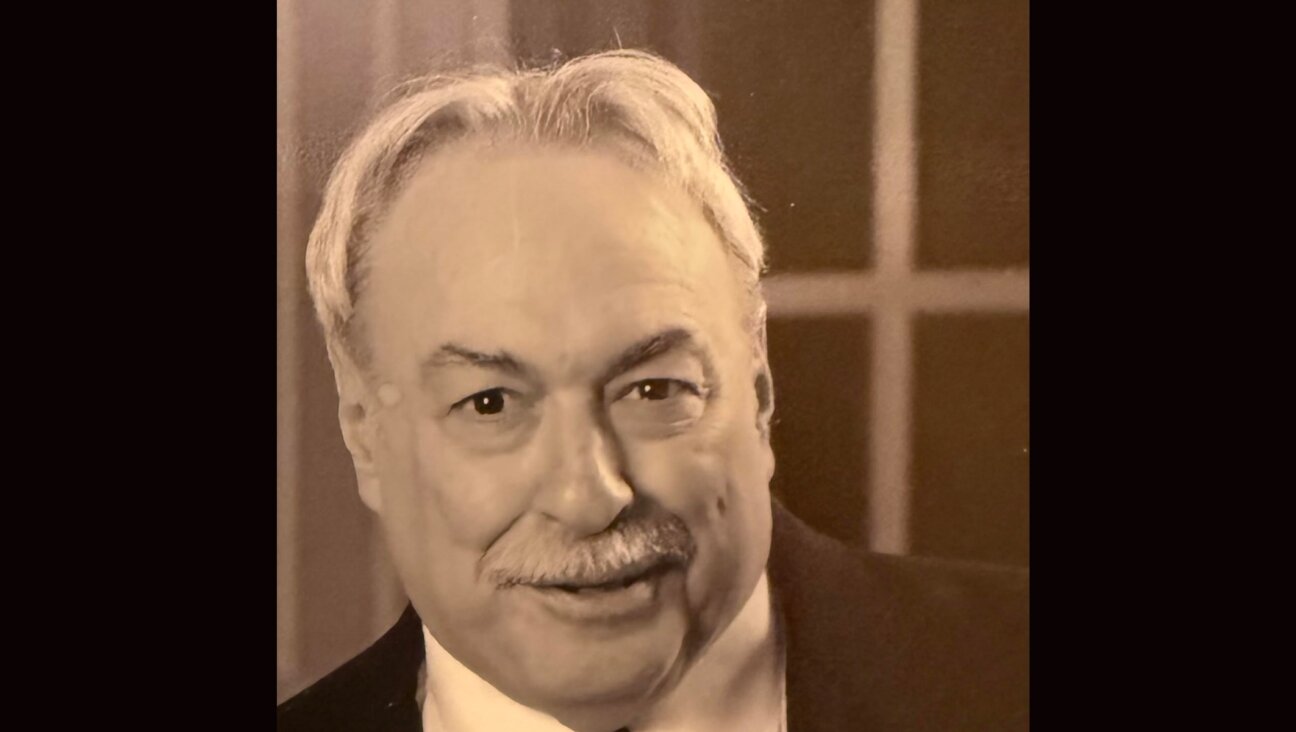

School?s Out Forever: Karen E.H. Skinazi stands outside her children?s shuttered day school. Image by shulamit seidler-feller

“I assume the oldest has taken his ERBs?”

“His huhs?” At that time I hadn’t heard of the Educational Records Bureau assessment test for independent school admission. It was like the moment at the interview when they ask you why you want to work at Apple, and you realize you are not sure if they make hardware or software or pie.

“It’s too late,” she said, “if he’s already 5 and a half. And we’re full.” A flat dismissal — before I even told her we were going to be a family of five living, at the time, on a pitiful academic salary and needed something in the ballpark of 100% tuition remission!

When we realized New York was not the panacea for our Jewish needs, we opted, ironically, for the WASPiest part of New Jersey: Princeton (as luck would have it, we both eventually got jobs at the university there). We found a lovely haimishe day school that was kind of far but wasn’t full and didn’t require academic testing. Instead, the school happily took us in — midyear at that — and gave us tuition assistance and sent a bus right to our door and made us a part of its little family. It was Solomon Schechter Day School of Raritan Valley.

Our school called itself Conservative, but we were pleased to see that it had a range of kids, from the tzitzit crowd to the heretic types (that was us). It’s where my oldest learned to read and write Hebrew fluently in the first month of first grade (before English!); where the kids in his class so loved the “Ariot” Hebrew curriculum that one hosted an “Ariot” birthday party (take that, Chuck E. Cheese!), and where everyone knew everyone’s name, from kindergarten through eighth grade. All was good.

Only all was not good.

The school was not competitive — could not demand ERBs or declare itself full — because, like many suburban Jewish day schools, it was low on students and high on debt. Behind closed doors, those same people who approved our tuition assistance were realizing that it was impossible to run a school on the revenue they had. At its peak, the school, which opened its doors in 1981, had more than 300 students. And perhaps most of them had paid in full. This was not the case in 2013. An email was sent out to the parents Tuesday, August 6, three weeks and two days before the first day of the 2013–14 school year announcing an emergency meeting.

It’s not that I didn’t see the email — not that I didn’t remark on its odd urgency — but I can’t say I did anything other than remark on it when I saw it. I was preoccupied with getting my own start-of-semester prepared. I had to order books, revise my syllabus, arrange for a film screening — the usual.

Other parents, apparently recognizing that this was not your typical Here’s-the-updated-calendar or School-supply-lists-can-be-found-here email, thought to ask what the hell was going on.

The next morning — Wednesday, August 7 — a second email arrived in my inbox.

“Dear Parents,” it read, “I would like to apologize for the cryptic nature of the email that I sent about tomorrow’s parents’ meeting. I should have realized how unsettling it would be to receive such a message without any details…. Unfortunately, I have to confirm what is, for all of us, the worst possible news for our school. Based on our current financial situation, the Board has voted to begin the process of closing down the school, effective immediately.”

I read the email three times, thinking I must be misreading it. I tried to call my husband, but I have no cell reception in my office, so I ran down the hallway frantically, yelling: “The school is closing! The school is closing!” When I got outside, I tried again, but somehow he still couldn’t hear me. I switched to texting, which was even less effective. “What school? Princeton?” he asked. Now that would be lousy, seeing as it employs both of us. Also, just a wee bit unrealistic, what with its $17 billion endowment, almost 300-year history and 7% acceptance rate. “Boys!” I typed. I have a phone from the 20th century, the kind that requires I click the mno button three times to get the “o” in boys. It’s laborious. He texted back, “But the boys are in camp.”

The back-and-forth between my husband and me was the very beginning of what seemed to be an endless series of communications and miscommunications to take place over the next week. First, the school was closed “effective immediately.” Emails began pouring in about other Solomon Schechter options. One Schechter, 20 minutes farther away from us (our school was already 35 minutes from our house — without traffic), was inviting our students to come; it would honor all financial aid packages and also offer free busing. Then, a second Schechter piped up with a near-identical offer. That school is more than an hour from our house. There was something vulturelike about the way the schools were quickly moving in on the displaced students, but we all understood: Here, in suburbia, we weren’t competing to get into the Jewish schools — the Jewish schools were competing for us.

Personally, I gave myself a day of mourning, and then I began to make my phone calls.

That Friday, I found a Jewish school across state lines. “Hi there,” I said. “I’m in the market for a new school. Do you do gifted and talented?”

“Of course,” the head of school replied. “This is a Jewish school. I’m told all our kids are gifted and talented.”

This sounded promising. “Can I come see the school?” I asked. We arranged a time. An hour later, an email pinged into my inbox. Emergency meeting at Schechter. This would be the third of its kind. But for what? Weren’t we closed? To wrap up loose ends? To berate the board for mismanagement? To sit shiva? Why go?

I went. There was a big crowd of parents, rabbis, community leaders, former board members and former parents. New plan: If we can pull together, we are not going to close. Come August 29 (or maybe September 9), if we’re all here, we are going to open our doors. If we all work together, we are going to find a way to be financially solvent, and we are going to get back the students who have been eyeing other schools appreciatively. Almost everyone is supportive. People pledge to raise money. People pledge to give money on the spot. Teachers agree to take wage cuts. By the end of the night, close to midnight, I have hope: The school might really be saved. The doors of the school might open, after all.

Hurray! We almost ended the night happily in “Kumbaya” or “Hatikva” or “God Bless America.” We felt proud that we had banded together and saved a day school, an establishment that not only educates Jewish children in secular America in the almost-forgotten culture and rituals of our people, but also acts as the glue for the community.

Admittedly, the next day, I went to see the other school — just in case. And it’s beautiful: purple walls in the girls’ Sephardic-inspired beit midrash; an Israel room featuring a “Superjew” shirt and computers representing Haifa’s Silicon Valley, along with the more traditional Jerusalemite fare, and a Holocaust library with the kids’ own family photos. There is a big indoor jungle gym for when the wee ones want to blow off steam in the winter. And Orthodox feminist Blu Greenberg is consulted when the school needs to figure out how to meet the demands of its pluralistic students. This charming school in leafy Pennsylvania is as religiously diverse as that school I once called in the city. I told the principal I’m impressed (I am!), and also that I will have to let him know if we’re coming once we see what happens with Schechter.

And what is happening with Schechter? No one knows. The optimism is fading. A questionnaire was sent out. Will you come if we open our doors? An informal poll followed: Will you come if we open our doors? Phone calls: Will you come? Will you come? We count the kids who say they will come. In each grade, about seven. Six other kids for my kid to play with. Three other boys for each boy to do boy stuff with. The parents have scattered, have registered at that other Schechter that pointed out it’s not only honoring financial aid and offering free busing, but is also stable. That’s the word that keeps showing up: stable. We are a stable school. We offer our children stability. We will provide a stable for your little butts to inhabit. Well, maybe not that one. But “stable” stands in sharp contrast to our Schechter, which continues to head each message with that conditional “if.” If we open our doors. If. If. If — that great hallmark of instability.

Outside of the polls, formal and informal, parents are texting and emailing and Facebook messaging and calling among themselves. “What are you thinking?” “The opposite of what I was thinking yesterday.” “No kumbaya?” “Will you go back?” “I’m not sure… but I called the local Orthodox day school.” “What are you thinking now?” “I am letting the kids play with their Schechter school supplies.” “And now?” “I just bought three pairs of tzitzit.” “So you made your decision?” “No, we’ll see…. Will it open its doors?”

Scheduled for Thursday, August 15, exactly two weeks before the doors of Schechter are supposed to open: another emergency meeting! This one was prefaced with an if-free email. We’re going ahead! This is our go-ahead plan! We are opening our doors. Come on in!

But by now, the school supplies have been played with, the tzitzit have been bought.

Our school, which in 2012–13 had more than 120 students now had 40 students or so saying they’re coming back. The doors are opening, but — . We’re no longer an “if,” but a but —.

Or no but. The meeting ran long and late, and again, the optimism was heady. The next morning, emails and phone calls abounded: The doors will be open! We did it! We raised lots of money and ruach, spirit, and all’s a go. That was the message at 8 a.m.

And yet — the but: When pushed against the now-open door, my husband and I had to say what too many other parents had to say. We can’t do it. Because this Schechter is not the Schechter of 2012–2013. And we can’t send our kids to this Schechter — not without critical mass for our classes. Not without the teachers we were coming back for. Not without the bus that would save us three hours of driving each day. By the time the Sabbath rolled in — a mere 13 days before the first day of school — another message was delivered. Dear parents, our doors will not open, after all. Funding they got; loyalty they lost. Open and shut, open and shut, open and — because people could never be sure that the doors wouldn’t shut yet again — forever shut. Solomon Schechter of Raritan Valley is no more.

I’m a little jealous of those schools in Manhattan that have a supply of students creating so much demand that they can’t even meet it. That’s not the case in most of New Jersey, not so in Pennsylvania. And it’s probably even less so as you get farther away. Here, Jewish friends look at me with plain disdain in their faces as they ask why I am sending my kids to Jewish school. I want to say to them: “Don’t you want this, too? Don’t you want your children to know where they come from? To be able to pray with a minyan? To know to sing ‘Od Yishama’ at a wedding or say ‘Ha-Makom yenachem etchem betoch sh’ar aveilei Tziyon V’Yerushalayim’ at a shiva? To be able to read from the Torah at their bar and bat mitzvahs in Hebrew that hasn’t been transliterated? To dream through the stories of I. L. Peretz and S. Y. Agnon? To deftly explain the differences between the destruction of the two Temples?”

But I don’t say this, because I’m not really sure anyone cares about the Temples. This isn’t New York. There, the doors on the Jewish schools — heavy, solid, stable — open narrowly, admitting those who meet their criteria. Here, the doors fling open wildly, admitting everyone, but they are flimsy, with not enough will or belief or funding to give them strength. And with a gust of wind, the doors slam shut. For good.

*Karen E.H. Skinazi is a literary and cultural critic, a lecturer at Princeton University, the wife of a scientist and the mother of three boys.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO