Philologos vs. Dovid Katz, Round II

Last week’s column ended with a brief description of linguist Dovid Katz’s theory of the origins of Yiddish. Succinctly restated in Katz’s newly published history of Yiddish “Words on Fire,” this theory holds that the first speakers of Yiddish did not arrive, as is generally assumed, in a German-speaking area of Europe from elsewhere on the European continent, but rather directly from the Middle East. The language that these immigrants brought with them and from which they switched to German, Katz believes, was Aramaic, the Semitic sister of Hebrew spoken by Palestinian and Middle Eastern Jewry until it was gradually replaced, following the Muslim conquest of the region in seventh century C.E., by Arabic. Judeo-Aramaic, the language of the Talmud and other early rabbinic literature, had in it an enormous amount of Hebrew, which, Katz claims, immediately became part of the new Judeo-German speech that eventually came to be known as Yiddish.

We spoke last week of why, ideologically, a Yiddishist like Katz finds such a theory appealing. But Katz is also a linguist, and a good one. What linguistic evidence does he have for his beliefs? For this, one has to turn to his more technical papers, such as “The Proto-Dialectology of Ashkenaz” or “Hebrew, Aramaic and the Rise of Yiddish,” in which he marshals several lexical and phonetic arguments on his behalf.

The lexical case starts with the fact that Yiddish has a much higher percentage of Hebrew and Aramaic words in its active vocabulary — well more than 10 % — than does any other known Jewish language of Europe, such as Judeo-Spanish or Ladino, Judeo-French, various dialects of Judeo-Italian and so on. How can we explain this if the original speakers of Yiddish came from elsewhere in Europe and switched to Judeo-German from one of these languages? From where did all of Yiddish’s Semitic vocabulary come?

The standard answer to this question is that this vocabulary came from an intensive familiarity with biblical and rabbinic literature. Ashkenazic, Yiddish-speaking Jewish communities, it is maintained, were better educated than Jews elsewhere and had more comprehensive institutions of Jewish learning. Therefore they incorporated more words from classical Jewish texts into their speech. The “text theory” of the pronounced Hebrew component in Yiddish was developed elaborately by the greatest of modern Yiddish linguists, Max Weinreich, and accepted by nearly all his disciples.

However, the “text theory” has its problems. To begin with, it is not at all clear that other Jewish communities in Europe were inferior to Ashkenazic Jewry in learning; in the period in which Yiddish first developed, the Jews of Spain, southern France and Italy had a high level of Jewish education, too. Moreover, as Katz observes, many Hebrew words in Yiddish are everyday adverbs and prepositions (such as kimat, “almost”; beshas, “during”; makhmes, “because of”; etc.) that are unlikely to be borrowed from sacred texts and don’t have parallels in other Jewish languages. And in addition, there is an almost invariable law in Yiddish that when two or more Hebrew synonyms are found in biblical and rabbinic literature, Yiddish chooses the chronologically latest of them. (For instance, the Yiddish word for “holiday,” yontif, comes from rabbinic yom tov rather than biblical hag or mo’ed.) This might indicate that Yiddish did not take such words from sacred texts but instead inherited them from a chain of transmitted speech.

Katz’s phonetic evidence is varied, too. To take one interesting case, he points out that there is a “systematic correspondence” between the articulation of vowels in German and Hebrew words in all dialects of Yiddish. Thus, for example, just as German hund, “dog,” is hunt in the Yiddish of Lithuania and hint in the Yiddish of Poland, so Hebrew guzmah, “exaggeration,” is guzme in Lithuania and gizme in Poland, and so on all the way down the line.

The logical conclusion from this, Katz argues, is that Yiddish’s Hebrew vocabulary entered it together with its German vocabulary “on touchdown,” that is, with the first generation of Yiddish speakers, thus ensuring that German-derived and Hebrew-derived words underwent the same vowel shifts as Yiddish spread to different areas and diversified. This is not what might have been expected to happen had Hebrew words been absorbed slowly by Yiddish from sacred texts throughout the centuries. Since Polish Yiddish, for example, has its own “u” vowel (as in khusn, “bridegroom,” in contrast to Lithuanian khosn), Hebrew guzmah, had it been borrowed from a text at a later time, after the vowel shift from hunt to hint had taken place, would have been guzme in Poland, too.

Katz’s arguments are good ones, and not to be lightly dismissed. The problem with them is not so much linguistic as historical. Assuming even, that is, that the linguistic evidence could be best accounted for by a hypothesized group of Middle Eastern, Aramaic-speaking Jewish immigrants to a Germanophonic area of Europe somewhere around the year 1000, which is the earliest date for the origins of Yiddish supposed by anyone, is there any reason to believe that such an immigration actually did or could have taken place?

Stay tuned. We’ll deal with this question next week.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

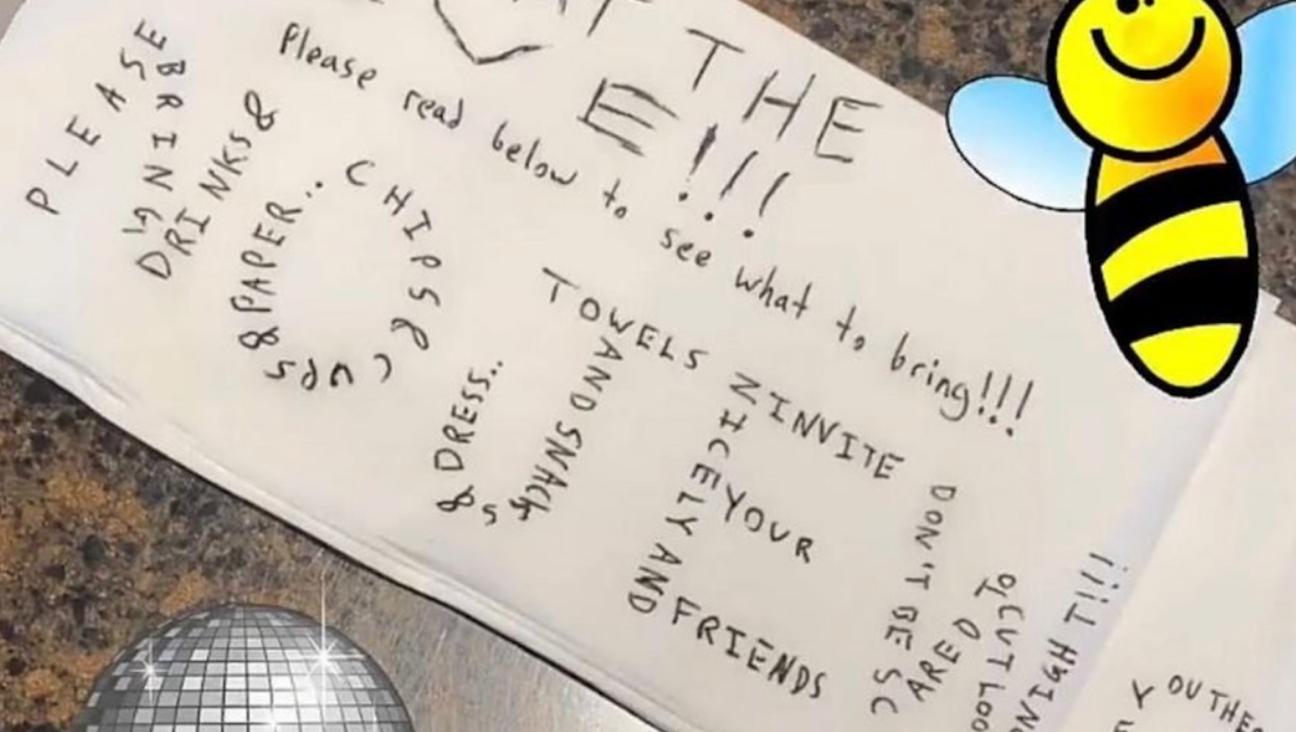

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

- 3

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 4

Fast Forward Columbia staff receive texts asking if they’re Jewish, as government hunts antisemitic harassment on campus

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Trump nominee Ed Martin, who praised a Nazi sympathizer, also compared Biden to Hitler

-

Opinion RFK Jr. and Trump are talking about an ‘autism registry’ — this sounds disturbingly familiar

-

Fast Forward Heavy police presence blocks anti-Israel protest in Brooklyn from reaching Jewish neighborhood

-

Yiddish קאָקני־ייִדיש“: אַ פּאָדקאַסט, אַ לשון און אַ שטײגער לעבן‘Cockney Yiddish’: A podcast, a language and a way of life

צװײ לאָנדאָנער היסטאָריקערינס לעבן אױף דאָס ייִדישע „איסט ענד“ אין אונדזער פֿאַנטאַזיע

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.