‘Stumbling Blocks’ Cobblestone Memorials to Murdered Jews Spread in Berlin

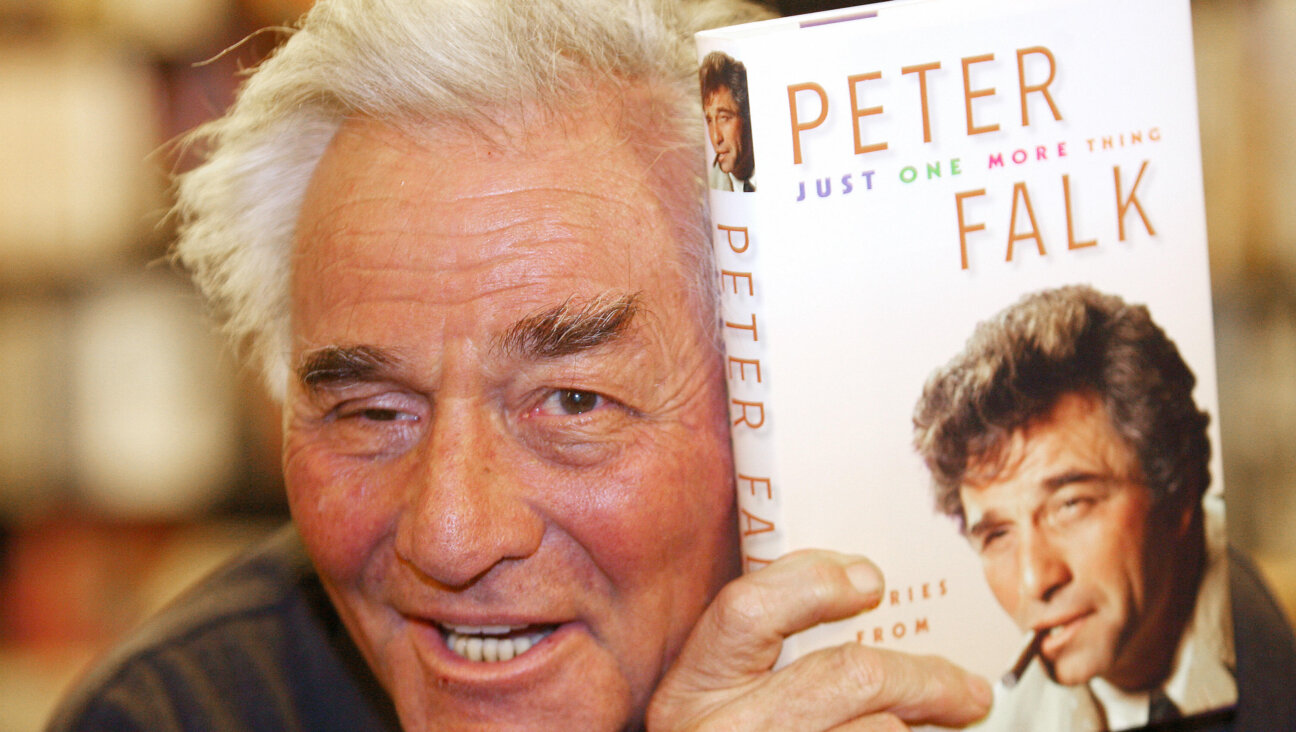

Step in Stone: German artist Gunter Demnig works on his ‘Stumbling Blocks’ Holocaust memorial. Image by getty images

(Reuters) — Veronika Houboi watched as a man in a cowboy hat and clogs wielded a sledge hammer to smash up and remove a dozen small cobblestones from a Berlin pavement.

He quickly filled the resulting hole with two identical blocks of concrete capped with inscribed square brass plates.

The blocks, called “Stolpersteine” or “stumbling blocks,” read: “Here lived Dr. Erich Blumenthal, born 1883, deported 29.11.1942, murdered in Auschwitz. Here lived Helene Blumenthal, born 1888, deported 29.11.1942, murdered in Auschwitz.”

In Berlin, the blocks have become part of the fabric of the city, their plates glinting amid the grey paving on residential streets and stopping both locals and tourists in their tracks.

Houboi and her husband sponsored the Blumenthals’ blocks, travelling across Germany to see them laid in the northeast Berlin neighbourhood where Houboi, now 71, grew up in the 1940s.

As a child, she had been moved by a story about the family’s local doctor, who had defied Nazi laws banning Jewish medics from treating non-Jews to care for her critically ill brother.

Unable to find the name of that doctor, Houboi decided to symbolically honour him by commissioning blocks for another local Jewish doctor, Dr. Blumenthal, and his wife.

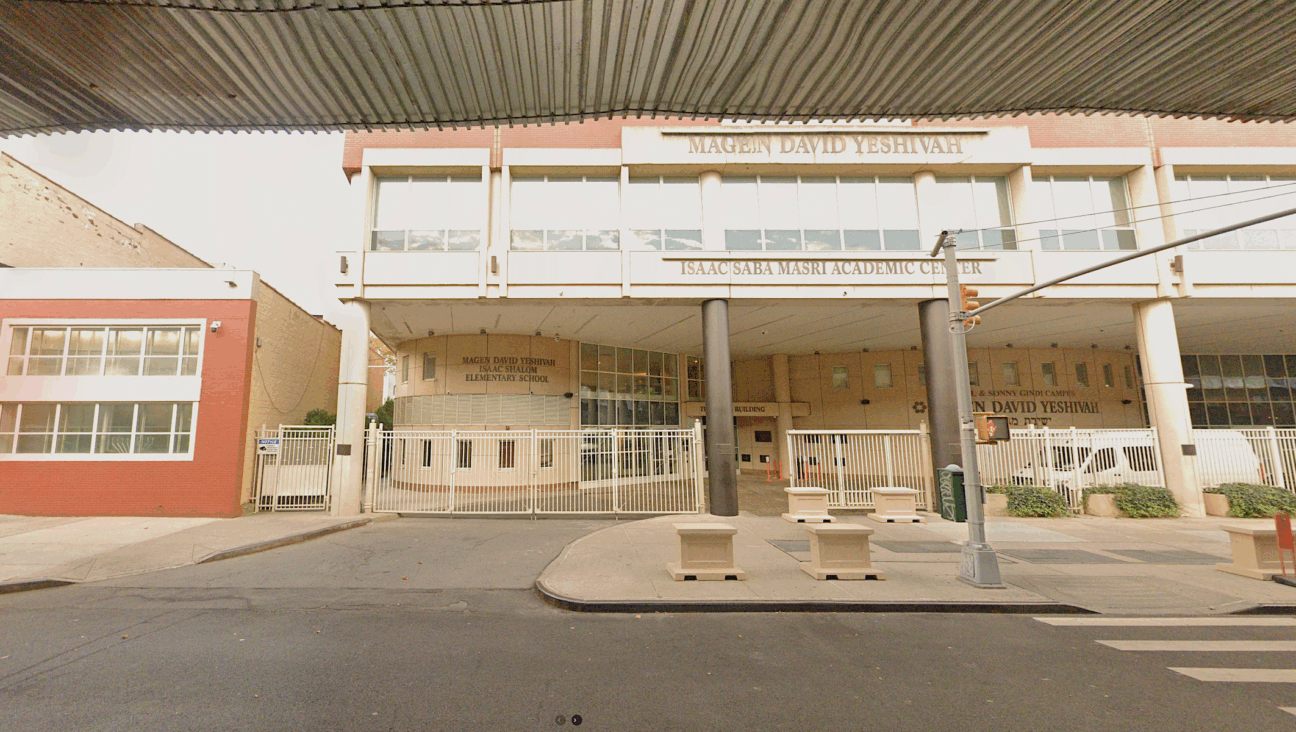

The man behind the stumbling blocks is Cologne-based artist Gunter Demnig, who in 1996 illegally laid the first 41 in the Berlin neighbourhood of Kreuzberg, having found the names in a local history book about the area’s Jewish population.

Three months later, the city granted Demnig permission to legally proceed with the project. Today there are 45,000 “Stolpersteine” in Germany and 16 other European countries. Berlin alone has 5,500 of them.

RISING DEMAND

After working on an art project commemorating the Nazi deportation of Cologne’s Sinti and Roma itinerants, Demnig became determined to show how victims of the Holocaust had been an integral part of German and European society before the war.

“The idea was to bring back the names (of the deported) in front of the houses where they had lived,” Demnig said. He added that Germans today had a greater desire to remember the atrocities of the Holocaust than when he was a child.

“In my school, history stopped with the Weimar Republic, because the teacher wasn’t interested … but now young people really want to know,” said Demnig, who was born in 1947.

Demand for the stones has been steadily rising in recent years, as the project has become better known abroad. Demnig’s team installs on average 5,000 to 6,000 stumbling blocks a year across Europe, the majority of them in Berlin.

The stones are commissioned based on requests by relatives of victims or by neighbours present and past, like Houboi.

At 120 euros ($170) a stumbling block, Demnig’s business is booming. Customers often have to wait up to a year, he said.

Demnig denies accusations he is profiting from the enterprise. “One cannot say it’s a business. It’s a piece of art … Artists have to live from their work,” Demnig said.

The project is largely privately financed. In Berlin, an independent coordinating agency funded by the city works with volunteer groups and museums to field requests and do historical research on victims like the Blumenthals.

Also at the installation with Houboi was Colonel Erez Katz, the Israeli defence attache to Germany and Austria. Katz has been moved by Demnig’s work and planned to spend the day with the artist as he installed stones at 12 different Berlin sites.

Katz said he took every Israeli military delegation that visits Germany to view the stumbling blocks.

“How German people remember the Holocaust surprised and impressed me. Every street has these stones. They take responsibility,” Katz said.