‘The 4th of July is one of the holiest days of the year:’ Readers share their Jewish stories of the holiday

‘No one wanted us but America. So we have to observe her birthday and respect this country’

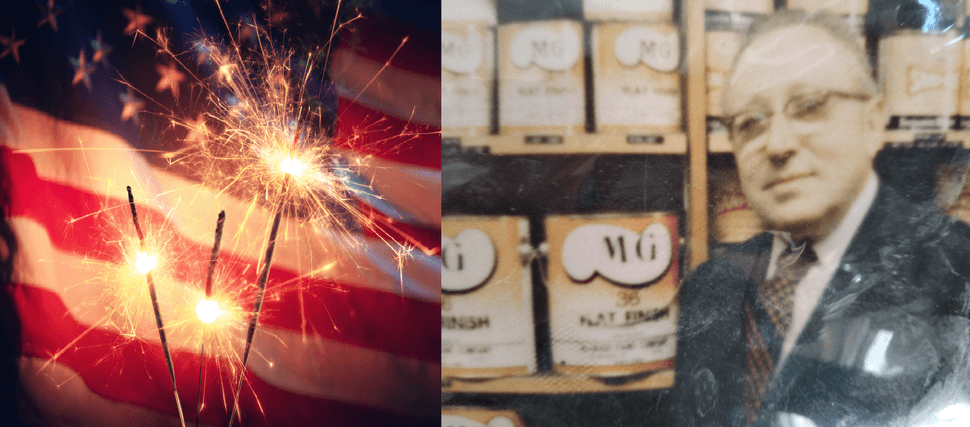

Photo by iStock by Getty Images

It’s time for fireworks, picnics and kosher hot dogs! Jewish Americans have always celebrated the Fourth of July in their own way. This year, The Forward asked its readers and contributors to send us the stories of their most Jewish Indepencence Day. Here, you can read their stories of celebration. And may your Fourth be a memorable one too.

I’m so glad it’s finally here as I can’t wait much longer. Memorial Day was so long ago and I really need to purchase some new summer clothes. On sale.

Isn’t that what July 4th is all about? Freedom to choose which store to browse.

Growing up, I attended the BALA school of business at Queens College where I completed the minor portion of my BA. I have fond memories of the classes but there is one that stands out in my mind. One of the business classes I took fell out on a Wednesday, and each week, without missing a beat, the professor would say — I’ll try to end on time today. I don’t want any of you to miss Macy’s One Day Sale.

The one day sale that happened every week.

The excitement. The energy. I remember spending hours at a time at Woodbury Commons, trying to hit every store in the span of a day. An impossible feat yet the thrill of the game nevertheless.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks in his work A Letter in the Scroll discusses the Exodus from Egypt and comments that although when the Jews left Egypt they were no longer slaves, “they were not yet a free society.” One can be out of shackles yet still imprisoned. He can be enslaved to their jobs, their tempers, their addictions. She might live in the land of liberty, but feel enchained to their choices and to the reputations they must live up to.

As you wait in line in Macy’s this July 4, take the time to ask yourself — do I use my freedom properly? Do I see reality objectively or do I let our own biases get in the way? If we can answer these questions affirmatively, we will truly taste freedom. —Meira Spivak

My father, Max, was a (Fulda) German Jewish refugee to America. He arrived near to 1941 after release from Buchenwald concentration camp but that’s another story. He was in his own business by the 1950s, open seven days a week. He closed the store only for the Jewish High Holidays, Christmas Day, and the Fourth of July.

I asked him once as a child, “Why close the 4th of July? It’s not a religious day.” In his thick, Henry Kissinger sounding accent he told me in no uncertain terms, “The Fourth of July is one of the holiest days of the year. It’s given by God as a blessing to people who have nowhere else to go. You don’t know because you are born here. But I know and Fred (his younger brother) knows. No one wanted us but America. So we have to observe her birthday and respect this country.”

Dad was no philosopher. He dropped out of school at 15 to work. But the man had heart. Gratitude. Graciousness. —Harold Goldmeier

The fourth of July in Los Angeles in the 1970s brought invitations from my school friend’s backyard BBQs. Keeping a kosher home meant that most foods were off-limits for the holiday: cheeseburgers with heaps of ham & potato salad, shrimp skewers, deviled eggs with crispy magical bacon, glistening wobbly gravity-defying jello, and to finish a huge slice of butter and lard filled crusted cherry pie. It was my eight-year-old American Dream.

If you were a goy-American, you could eat anything you wanted, as much as you wanted. No restrictions, no sorry kid that is not kosh. A dream denied to me as a kid, in my saggy knee socks and long sleeves, staring at the American buffet of prosperity and promise. No, sorry, I can’t have any. I brought my lunch with me in a leaky Tupperware container with an olive oil egg salad on soggy bread, radishes cut into flowers, celery sticks, and two cookies. —A. J. Campbell

Growing up, my family spent the summers at a bungalow colony in the Catskills. All the parents were first-generation American Jews. Like me, my friends had grown up hearing how their grandparents had fled the pogroms of Russia and Eastern Europe.

America was their promised land.

July 4th was always eagerly anticipated. Since most of the colony’s families were NYC apartment dwellers, the idea of fireworks showering against a midnight sky, no streetlights or high-rise buildings to intrude on the darkness, was wondrous as a fairy tale.

There was one hitch: In New York, fireworks were illegal. We had to be content with sparklers.

One summer, my father returned on July 4th from his annual two-week stint in the Army Reserves in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Unpacking his suitcase, to my amazement, he pulled out a package of Roman candles.

Nothing was illegal in Oklahoma.

As darkness fell on the Fourth, my father strode out to the center of a large, grassy field in the middle of the colony. The bungalows were arranged in a horseshoe around it. Carrying the Roman candles and a stake, he hammered the stake into the ground, as the men, women and children of the colony circled the field. Flashes of light burst from sparklers they held, as if heralding the coming event.

My father wasn’t a tall man, but as the lone figure on the darkened field, his presence towered over the upright candle. Arms outstretched, he stepped forward and lit the fuse. There was a collective gasp as the first flare erupted. Oohs and ahs followed, as heads upturned, sparklers rising, the movements mirrored the flare’s path higher and higher until it exploded. Over the darkened earth, colored starlight filled the sky.

In that moment, my father created the heavens. —Susan Baskin