The Racists Around Us

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Blood and Politics: The History of the White Nationalist Movement From the Margins to the Mainstream

By Leonard Zeskind

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 672 pages, $37.50.

To most Americans, including seasoned political observers, the machinations of white supremacists and professional antisemites are regarded, if at all, as crude carnival theater. After more than three decades of close observation, Leonard Zeskind, recipient of a 1998 MacArthur Fellowship for his independent scholarship on far-right, racist and neo-Nazi groups, is not so dismissive. More important, his first book, “Blood and Politics,” analyzes the past 35 years to provide a trenchant and troubling assessment of the future of what Zeskind terms “the white nationalist movement.”

Since the mid-1980s a number of books have detailed homegrown paramilitaries and the bigoted zealots behind them, but “Blood and Politics” provides an entirely deeper level of analysis. Zeskind is the first to fully integrate a sophisticated understanding of global events — specifically the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union — with an equally forceful insight into the uniquely American dynamics of racial identity, Southern sectionalism and national politics. After the Soviet Union “cracked apart like a three-minute egg,” and anticommunism became almost instantly irrelevant to American national identity, white nationalists rushed in to fill the vacuum.

The end of the Cold War dichotomy gave way to a new struggle, that of nationalism vs. internationalism, and the results of this “geopolitical earthquake” are still reverberating all around us, Zeskind explains. While most of the civilized world ostensibly looked on with horror as the multicultural communities of Yugoslavia disintegrated under the demands of ethnic nationalism, white supremacists and antisemites in the United States saw increased promise in the prospect of recasting their domestic struggle as both an ethnic and religious war.

The subtitle of “Blood and Politics” offers a history of the white nationalist movement “from the margins to the mainstream,” and the description is certainly apt. In the hands of less-skilled authors, navigating the netherworld of white supremacist groups too often becomes an exercise in cataloging the alphabet soup of one seemingly hapless sect after another. But Zeskind concentrates not only on painting the picture of a *movement *— which allows the plethora of people and groups he describes to fall into place more readily — but also on highlighting the critical fault line between “vanguardists,” who advocate violent, revolutionary struggle, and “mainstreamers,” who favor the ballot box over the bullet.

“Blood and Politics” elucidates this distinction chiefly through the personalities and political histories of two men who contributed perhaps more than anyone else to the development of the contemporary white nationalist movement. William Pierce, a physicist by training, was in the vanguard, while Willis Carto, a gray everyman with a background in sales, pushed toward the mainstream. Both were children of the Depression who came of age politically in the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education decision ending segregation, and both dedicated the balance of their lives to the cause of white supremacy and the extirpation of anything Jewish, but any similarity ended there.

Carto was the founder of the perennially vitriolic and “anti-Zionist” Liberty Lobby, which at its peak employed dozens of staffers in its Capitol Hill offices, had a multimillion dollar budget and circulated its house organ, The Spotlight, to hundreds of thousands of paid subscribers. As obsessively secretive as he was litigious, Carto made an indelible mark on the political landscape of white nationalism as the founder of both the Institute for Historical Review and the Populist Party. The former was dedicated to the proposition that the Holocaust was a hoax, but its real purpose was the rehabilitation of National Socialism as an acceptable political doctrine. The latter attempted to create a third party capable of moving racism and antisemitism into the political mainstream. Zeskind details the inner workings of both organizations, and exposes, for the first time, the full role played by Carto in these and other equally bigoted enterprises spanning some 40 years.

Where Carto sought to penetrate the ranks of mainstream conservatives, as well as peel off conservative constituencies to his own cause, Pierce had a more narrow view: He sought to recruit hardened cadres of violent revolutionaries, men willing to die for the cause of Aryan brotherhood and racial revolution. Pierce, who died in 2002, is perhaps best known as the author of “The Turner Diaries,” a phantasmagorical novel about an imagined race war. Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh was perhaps one of its most notorious fans. Pierce was a one-time acolyte of George Lincoln Rockwell, founder of the American Nazi Party, and went on himself to establish the neo-Nazi National Alliance.

“Blood and Politics” does more than simply tell the story of Carto and Pierce; it comprehensively exposes and illuminates a cast of characters who occupy places of particular importance on either side of the line dividing mainstreamers from revolutionaries, and thus contextualizes literally all the significant recent personalities and events within the white nationalist movement. While the political ascendancy of former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke has inspired countless exposés, Zeskind’s treatment of Duke’s political experiment more thoroughly explains the origins of the movement that gave rise to him and the one he subsequently helped shape. While the story of The Order, a 1980s-era band of bank robbers and would-be Aryan warriors, has been detailed vividly by a range of journalists and authors, “Blood and Politics” is the first book to fully articulate the tension between these vanguardists and their “mainstreaming” counterparts.

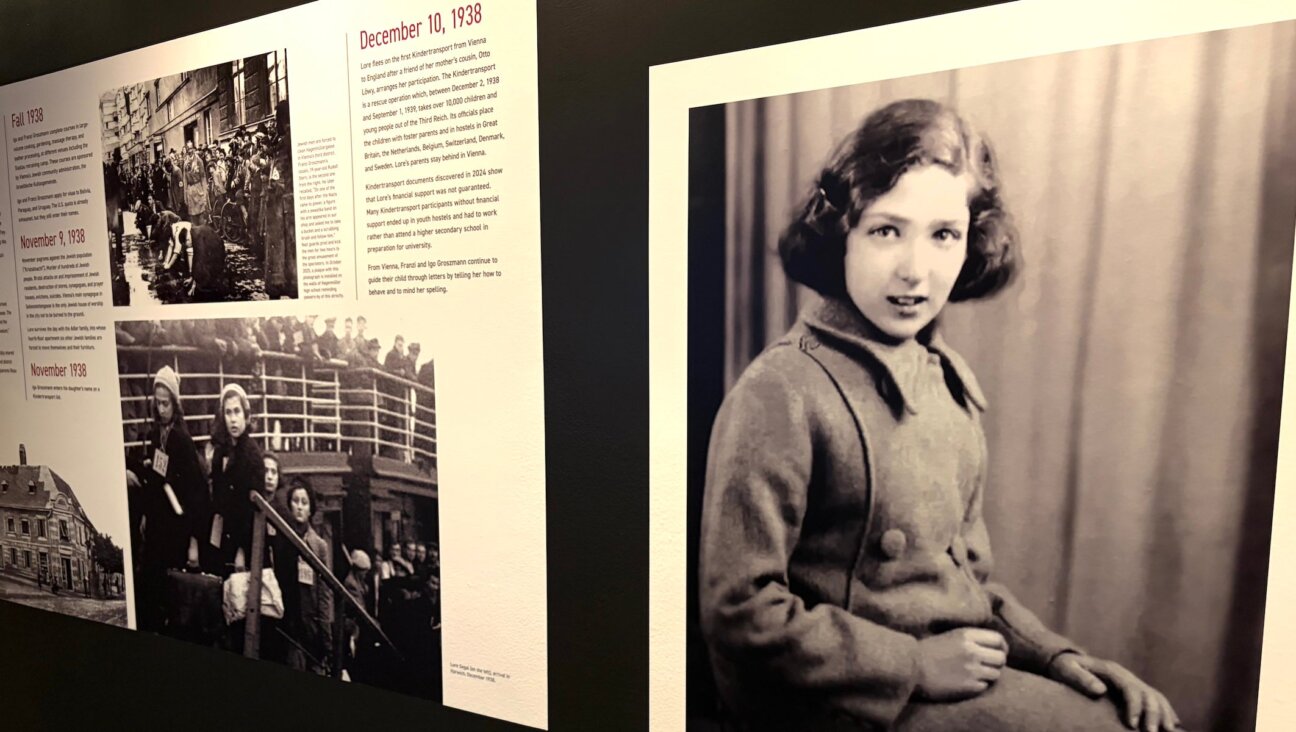

The descriptions are fresh, but the book suffers from an absence of photographs, which would have helped bring more of the scenes and characters to life. Zeskind takes his subject seriously, and refrains from caricature; but he is not beyond crafting colorful prose occasionally ladled with well-deserved derision. Nestled deep in the Ozark Mountains, the Covenant, the Sword and the Arm of the Lord was one of the most heavily armed paramilitary compounds of the mid-1980s. Zeskind describes it:

Weapons of every description were cached around the camp like sacks of wheat for a future famine. Light antitank weapons, known as LAW rockets, dynamite, and military-style plastic explosives were hidden. So was a thirty-gallon barrel of cyanide and forty thousand dollars worth of gold coins, Krugerrands, the currency of the apartheid regime in South Africa…. [T]he CSA was ultimately a heavily armed and criminal compound for cultists. Atop this gunpowder dung heap sat James Ellison, like a combination guru and Gruppenführer.

Zeskind also takes aim squarely at former syndicated columnist Samuel Francis — a paleo-conservative stalwart — and his journalist-turned-politician colleague, Patrick Buchanan, who stunned the Republican political establishment with his first-place finish in the 1996 New Hampshire presidential primary and went on to poll more than 3 million votes by hammering away at brown-skinned immigrants, embracing the Confederate flag and excoriating abortionists. Buchanan was “a white Christian nationalist, first and foremost,” Zeskind reminds us, before detailing the healthy smattering of professional racists and antisemites who peppered the state leadership of his national campaign.

“Blood and Politics” also reprises the success of such old-line segregationist groups as the Council of Conservative Citizens, which changed its name but not its racist agenda. Most important, the council claimed an array of local, state and federal elected officials as their allies, including former Georgia congressman Bob Barr and former Senate majority leader Trent Lott, who were forced to distance themselves when their links to the council became front-page news.

Although antisemitism and racism are usually inseparable handmaidens within the white nationalist movement, some groups tried to parse their prejudices. It was an awkward endeavor. Jared Taylor, founder of the group American Renaissance, reveled in the pseudo-intellectual discourse of scientific racism, but he inspired the ire of fellow activists by giving a platform to such men as Rabbi Mayer Schiller, a teacher at Yeshiva University High School in Manhattan, despite the fact that the rabbi objected to “egalitarianism” and bemoaned the destruction of the white race as vigorously as any white supremacist.

As prologue, Zeskind recounts the bloody disintegration of Yugoslavia and notes that “in a matter of a few historical seconds,” this multiethnic state went up in flames. While Zeskind doesn’t predict similar violence in the United States, he does forcefully make the point that the inevitable midcentury demographic shift toward a minority-white nation has the potential to stimulate white nationalists of future generations to pursue a balkanization of their own design. No doubt some hardened movement activists will be spurred to commit violence, as they always have. More important, Zeskind warns us, others will seek to use politics to consolidate white racial and political identity in reaction to the inevitable demographic change. To do so, they will draw on symbols of the past to write their future.

The civil rights movement succeeded in abolishing de jure segregation, even if the rate of change fell short of the “all deliberate speed” mandated by the Brown decision. And the presidential election of Barack Obama certainly marks the success of America as a multiracial democracy, notwithstanding the need for continued progress. What remains an open question, in Zeskind’s eyes, is how well the nation will make the transition to become a multiethnic state in which white people are a minority. For those who are committed to making that changeover a successful one, it will be necessary to anticipate and understand the forces that are likely to be arrayed against them. “Blood and Politics” will be indispensable to that effort.

Daniel Levitas is the author of “The Terrorist Next Door: The Militia Movement and the Radical Right” (Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, 2002).