The Kitbag Question

Reporting on a visit by Israeli Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni to Sderot, the town near Gaza repeatedly hit by Qassam rockets, the Hebrew newspaper Ha’aretz had this to say about her meeting there with European Union foreign policy chief Javier Solana:

“In the course of a press conference…. Solana said that he understood the local residents’ pain and that ‘the European Union wishes to advance the peace process, which is the only solution and cannot be attained through violence.’ To a question from Ha’aretz about what he thought of the Israeli army’s [retaliatory] measures in Gaza, Solana said he thought that, so far, they were reasonable. Livni then said to the reporters with a smile [in Hebrew]: ‘And bring your kitbags.’”

Although most Israelis would have understood Livni’s seemingly odd comment unaided, Ha’aretz came to the assistance of those who might not have by adding the parenthetical explanation, “The [foreign minister’s] meaning was that the question was unnecessary.” Yet this, in turn, raises two more questions: Why did Livni think the question was unnecessary, and why did telling the reporters to bring their kitbags convey this?

Question one is political rather than linguistic: Presumably, the foreign minister thought that Israeli reporters should understand that this was not the time or place to embarrass the publicly peace-loving Solana with queries about Israeli military actions to which he had already privately acquiesced. Question two brings us to the Israeli slang expression “she’elat kitbeg,” a “kitbag question” — that is, the kind of question that only an idiot would ask.

Kitbags are something that most people see only on the TV news, when soldiers of one country or another are shown decamping for some military theater with their gear slung over their shoulders in what looks like a large canvas duffel bag. In it is whatever a soldier has received as army issue, or carries with him, that he is not wearing at the moment: an extra uniform, his helmet, his pouch, blankets, his personal clothing and possessions, etc. Originally called simply a “kit,” the kitbag was defined in 1785 by Francis Grose in “A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue” as “the whole of a soldier’s necessaries, the contents of his knapsack,” and it entered Hebrew as kitbeg via Palestinian Jewish soldiers serving in the British armed forces during World War II.

And what is a “kitbag question”? There are, in Israeli folklore, two opposed stories of how this term had its origin. In one of them, a squad of soldiers, being punished for some infraction of discipline, was told by its sergeant to take all its gear and run 100 times with it around the parade grounds. At which point, one squad member, obviously not the brightest, raised his hand and asked, “Our kitbags too, sir?” Since a kitbag with all its contents is very heavy, and no sergeant would ordinarily think of including it in such a command unless inspired by a very dumb soldier, one can imagine the groans that went up from the rest of the squad when this question was asked.

This is obviously not, however, the version of the story that Livni had in mind, because in that case she would have told the reporters, “And don’t bring your kitbags.” She was thinking, rather, of version two, in which the same squad is told that it is being transferred to another military base and should get all its gear together and be prepared to move out. “Our kitbags too, sir?” the same soldier asks. Since in this case, leaving one’s kitbag behind would mean permanently abandoning everything in it, the groan that went up from the rest of the squad was just as loud as it was the first time.

In Yiddish, a kitbag question is known as a klots-kashe, or “klutz question,” our English “klutz” coming from Yiddish klots, a block of wood. Jewish humor is full of klots-kashes. A Jew, for instance, is told by his friend of a marvelous new invention called an airplane. “One day, everyone will have one,” the friend says. “You’ll be able to get on your airplane here in Minsk and be in Moscow in an hour.” “But what will I do in Moscow when I don’t know anyone there?” the first Jew asks. A klots-kashe!

In proper Hebrew, on the other hand, a she’elat kitbeg is called a she’elat tam, which is a question asked by a tam or “simpleton.” This comes from the passage in the Passover Haggadah about the four sons — the wise son, the wicked son, the son who doesn’t know enough to ask and the simpleton who looks at the gala Seder table, with all its guests, and says, “What’s all this for?” The longer answer to this question is in the Haggadah. The shorter one is, “For this we spent $20,000 a year to send you to Hebrew day school?”

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

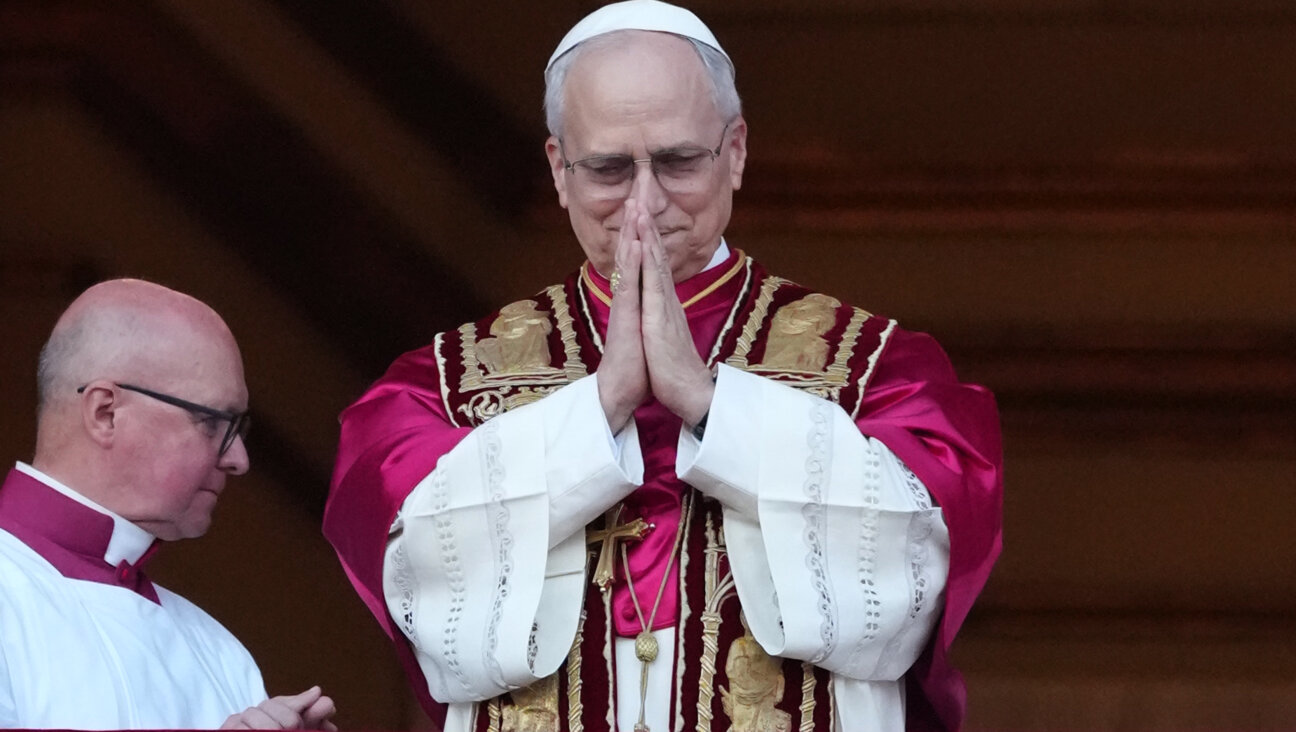

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture How one Jewish woman fought the Nazis — and helped found a new Italian republic

-

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

-

Fast Forward Betar ‘almost exclusively triggered’ former student’s detention, judge says

-

Fast Forward ‘Honey, he’s had enough of you’: Trump’s Middle East moves increasingly appear to sideline Israel

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.