Stop Talking out of Your Nose

Shelly Jacobson writes: My husband grew up in a Yiddish-speaking family in Brooklyn. Recently, I used the word *fumfah, *thinking this meant someone who made a big or embarrassing error in speech. I didn’t think it was Yiddish — it was just a made-up word to me. But my husband says it definitely is Yiddish and means someone who cannot express himself or get the words out. Do you know of this word? If so, what is its meaning?”

In standard Yiddish, without the Brooklyn accent, a “fumfah” is a fonfer, *a noun formed from the verb *fonfen. *The verb’s basic meaning is to speak nasally, so that a *fonfer *is someone who talks through his nose or as if his nose were stuffed. The word seems to have no Germanic, Slavic or Hebrew antecedents and is almost certainly onomatopoetic in origin, like the similar English verb “to humph.” Indeed, *fonfen *is one of those relatively rare words that can be uttered intelligibly without opening one’s mouth. Mrs. Jacobson’s husband’s understanding of *fonfer is close to this.

But *fonfen *and *fonfer *also have a gamut of secondary meanings. As listed by Leo Rosten in his always delightful and usually reliable “The Joys of Yiddish,” these are “a double-talker”; “a man who is lazy, slow, ‘goofs off’”; “one who does not deliver what he promises”; “a shady, petty deceiver”; “one who cheats”; “one who goes through the motions of a thing without intending to perform to his capacity or your proper expectations”; “a boaster, full of bravado”; “a specialist in hot air, baloney — a trumpeter of hollow promises.”

All these meanings are closely related, as is the Yiddish-derived British slang term of “a fonfen” in the sense of a con man’s spiel — but what does any of them have to do with speaking through the nose? I was pondering this question when, looking at the definition of fonfen *(“to snuffle, speak through the nose”) in the 1928 edition of Alexander Harkavy’s Yiddish-Hebrew–English Dictionary, I noticed next to it a most curious item: “Fonfe*: A lighted paper cone for blowing smoke into a person’s nose. (A trick.)”

A lighted paper cone for blowing smoke into a person’s nose as a trick? What on earth was Harkavy talking about?

And then it struck me all at once: Harkavy was confused. The paper cone was for blowing smoke not into the nose (it was fonfen’s meaning of “to nasalize” that led him astray), but into the ear, and what he was talking about — what he had been told about in an unclear way that prevented him from understanding it — was the old custom of ear coning or ear candling that was once practiced in Eastern Europe, as it was in many other parts of the globe, and that recently has been making a comeback as a 21st-century alternative-medicine technique.

Basically, this technique calls for lying on one’s side and having inserted into one’s ear the tip of a candle, or a wax-coated paper cone, that is then lit at its other end and slowly burns down toward the ear. The belief behind it is that the updraft of hot air caused by the candle or cone creates a vacuum or “chimney effect” inside the ear that sucks out wax, dirt and other unwanted matter and cleans out the nasal and sinus cavities. A typical treatment takes 10 minutes to a half-hour and is said to have many beneficial effects.

Alas, before you go running to the nearest ear coner, you should know that as far as the medical profession is concerned, the whole procedure is worthless and even dangerous. The respected medical journal The Laryngoscope*, *for example, has published a study concluding that ear coning does not create a vacuum, actually may deposit rather than remove wax and can lead to serious injury. Although it is said to go all the way back to the ancient Egyptians, it’s one of those healing methods that works only by suggestion and has no more efficacy than snake oil.

This brings us back to Leo Rosten’s definitions of fonfer. *What recently was discovered by the researchers of The Laryngoscope was apparently realized long ago by many of the Jews of Eastern Europe, who regarded ear coning as a hoax, the kind of thimblerig practiced by quacks and tricksters. (No doubt this is why, until its recent revival, the procedure fell into such disuse that Harkavy no longer grasped what its “trick” was and thought it some kind of practical joke.) The cone itself must have been called a *fonfe *because its dispensers promised that it cleared stuffed noses; from this came *fonfen, *to deceive or make unsubstantiated claims, and *fonfer, *one who does such things. Although the *fonfe *itself was forgotten, these meanings were not and have continued to exist to this day, alongside *fonfen’s original meaning of “speaking through the nose.” There is, it turns out more than one way to fonf.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

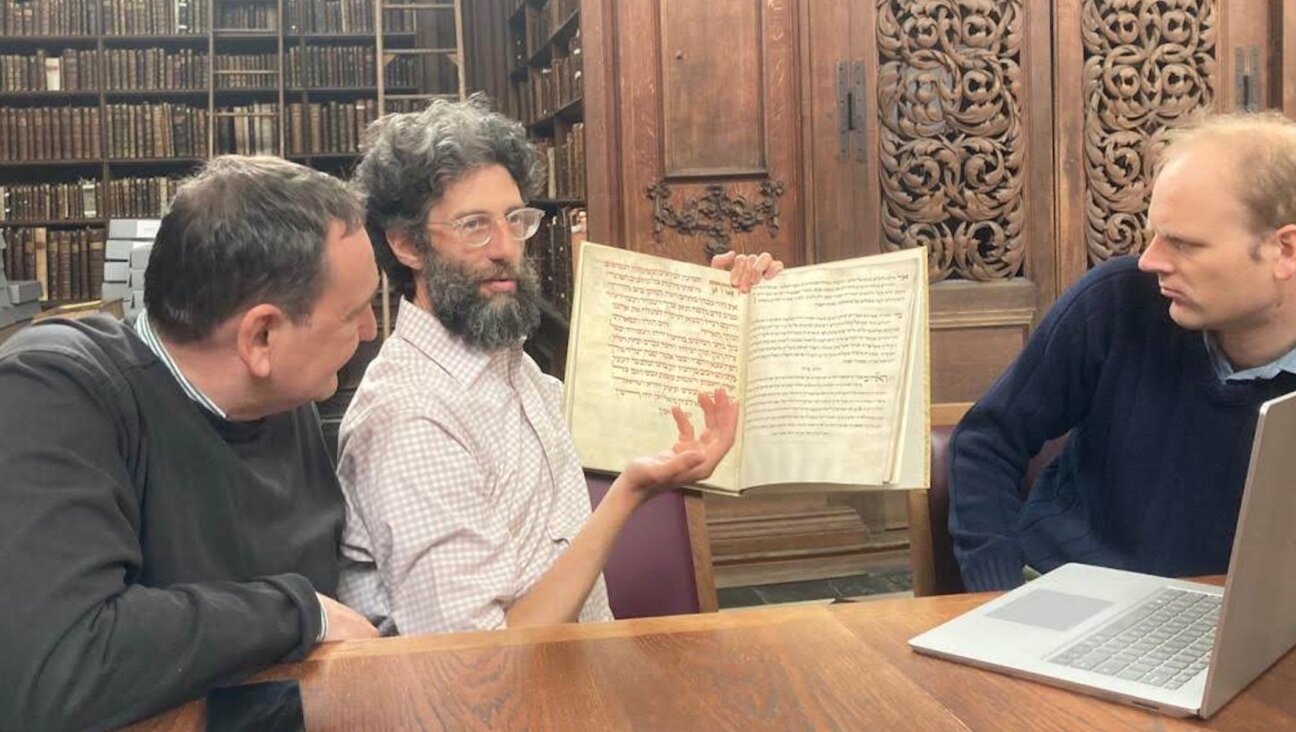

Fast Forward For the first time since Henry VIII created the role, a Jew will helm Hebrew studies at Cambridge

-

Fast Forward Argentine Supreme Court discovers over 80 boxes of forgotten Nazi documents

-

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.