Putting the Id in Yid

Forward reader Ben Warwick wants to know why the Yiddish words for a Jew and for Yiddish, yid and yidish, are often spelled with an initial alef rather than an initial yod, so that they appear in print as id and idish. This is something I myself have often wondered about. Now, under Mr. Warwick’s prompting, I decided to look for the answer. Luckily, I did not have to look very far for it, because I soon found it in a thorough discussion of the matter by Dovid Katz, one of the leading Yiddish scholars of our time, published in the New York Yiddish weekly Algemeiner Journal.

Katz’s article is simultaneously so erudite and so charming that I wish I could translate and print it for you in its entirety. Alas, it’s much too long for that, and I’ll have to make due with a charmless summary. Even then, the twists and turns of the story come through. Essentially, they can be divided into five chapters.

-

Throughout the Middle Ages and into early modern times, the Yiddish words for Jew and Yiddish, though commonly pronounced yid and yidish, were universally written as yud and yudish, with an initial yod followed by the vav, indicating an “oo” vowel. This may have been done under the influence of German Jude and Judisch, even though German “oo” changed to Yiddish “ee” at an early stage. In addition, Katz points out, the spelling of yid called for two yods, the first indicating the consonant and the second the “ee” vowel, and two yods standing by themselves are a traditional way of representing adonai, the Hebrew word for God. Loath to desecrate God’s name by using this yod-yod combination, pious Jews preferred the yod-vav of yud and yudish.

-

Starting with the 19th century, the spellings id and idish began to replace yud and yudish. This started among maskilim, or modernizing intellectuals, in Lithuania, in whose dialect of Yiddish the initial “y” consonant was actually dropped, id and idish being how the words were pronounced by them. From there, this spelling spread to the rest of the Yiddish-speaking world, where the initial ”y” was pronounced. At first it spread as a symbol of modernization, with more Europeanized Yiddish writers and publications opting for id and idish and more traditionally religious ones clinging to yud and yudish. Yet by the 19th century’s end, the Orthodox, too, were won over, and id and idish came to prevail everywhere.

-

This consensus, however, was short-lived. In the early 20th century, the modernizers, many of them now aggressively secularist and anti-religious, decided that id and idish were also outmoded. After all, why follow a Lithuanian spelling when most Jews did not drop their y’s, like Lithuanians? Id and idish now began to be replaced by yid and yidish, and the latter usage was eventually adopted even in Lithuania. Thus, when in 1925 a prestigious “scientific institute” for Yiddish studies was established in Vilna, it was officially called the Yidisher Visnshaftlikher Institut or YIVO, and not the Idisher Visnshaftlikher Institut or IVO.

-

The Orthodox world resisted the change, which it associated with secular Jewishness, and continued to spell the words id and idish. In this it was joined by much of the secular Yiddish press, which also favored the more traditional spelling. Under the tutelage of its legendary editor, Abraham Cahan, for instance, the daily Forverts continued to use id and idish, spellings it did not give up until the 1990s, when it finally switched to yid and yidish.

-

By the end of the 20th century, secular Yiddishism, or what remained of it, had switched to yid and yidish entirely, while Orthodoxy — or to be more precise, ultra-Orthodoxy — persisted in id and idish. How one spelled these words now came to define one’s attitude toward religion. The Algemeiner Journal, for example, being an ultra-Orthodox newspaper, has continued to insist on id and idish, to the point, indeed, that when Dovid Katz, a secular Jew, published his article there, this was how the words were spelled. And so, ironically, whereas 200 years ago it was the modernizers who fought for id and idish while Orthodoxy stuck with yud and yudish, id and idish have now become ultra-Orthodox banners in the fight against yid and yidish!

Yet Katz himself does not object to this. On the contrary, as someone who recognizes that spoken Yiddish’s only hope for survival is as the language of at least some ultra-Orthodox Jews, he favors tolerance for ultra-Orthodox preferences. After all, he writes in his article, all Yiddish educators “should be in seventh heaven over the language’s flourishing in traditionally devout circles” and should therefore “make it their duty to acquaint their students with the authentic Yiddish of our times.”

Or shall we say, the authentic Iddish?

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

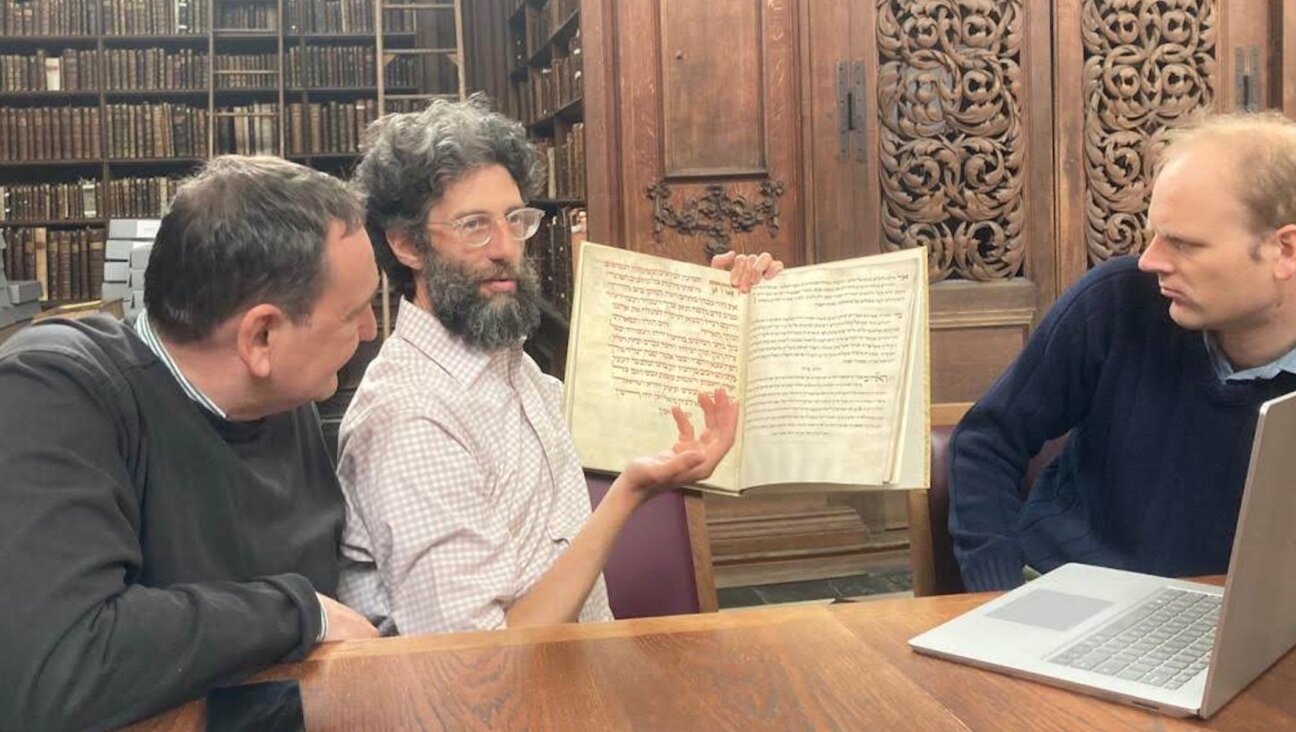

Fast Forward For the first time since Henry VIII created the role, a Jew will helm Hebrew studies at Cambridge

-

Fast Forward Argentine Supreme Court discovers over 80 boxes of forgotten Nazi documents

-

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.