Epic Encyclopedia Turns a Page in Study of Jewish Eastern Europe

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

What is Jewish Eastern Europe? A geographical space, or a frame of mind? The eternal homeland of Ashkenazic Jewry, or simply its birthplace? A field of academic inquiry, or just a touchstone for nostalgia?

DOUBLE EXPOSURE: The new YIVO encyclopedia also includes numerous illustrations. Two paintings of Jewish women, one dated from 1900 (left) and the other from 1911, show the progression of Jewish self-image in art.

For the editors of the comprehensive new YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, capturing di alter heym — the Old Country — was as much a dispassionate collabora-tion of scholars as it was a reckoning with these layers of complexity. All compilers of encyclopedias grapple with the challenge of determining their projects’ scopes, but the team behind the YIVO project was also tasked with creating a reference book that would capture a civilization that has, for the most part, been severed from point of origin. From the start, the project’s editors had to negotiate an unusual set of questions: Should the borders be cultural, linguistic or geographic? All three?

“The major debates were over the parameters of the encyclopedia — deciding on the geographical limits, the chronological limits (some wanted to include only the period before 1939), the decision to include only biographies of people who had done something important in Eastern Europe, the decision not to have separate entries on non-Jews, and the like,” said Gershon David Hundert, the editor-in-chief of the Encyclopedia and a professor of Jewish studies at McGill University in Montreal.

The two volumes that resulted, which will be published next month by Yale University Press, are notable for their range and depth. With entries on people, institutions, periodicals and movements, the encyclopedia covers the Jewish cities, ideas and personalities that, for over 1000 years, lived together between the Urals and the Rhine.

The idea for the encyclopedia — which was overseen by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research — arose in 1998 in response to the lack of a definitive encyclopedia covering East-ern European Jews. With a main grant in 2001 from the Conference for Material Claims against Germany and 18 primary sponsors, the project was inaugurated. An online version is currently in formation. For starters, Hundert enlisted a cadre of scholars who could write on a diverse set of subjects, from Marc Chagall to race science. The roster eventually expanded to include 450 contributors living in 16 countries, with the project itself recording changes in the field — including the growing international nature of the field of Eastern European Jewish studies and the political and social shifts that have made such a growth spurt possible.

“Submissions in English, Hebrew, Russian, German and Polish came my way,” said Gershon Bacon, a member of the encyclopedia’s editorial board and a professor of Jew-ish history at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. “This reflects a major change in the scholarly world over the last two decades, where new centers of research have sprung up in post-Communist Eastern Europe.”

But every decision brought with it layers of complex negotiation. For starters, the editors decided that the geographic scope would be the area roughly covering today’s Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Poland, the Baltic states, Finland, Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. But, in at least one instance, this led to a thorny debate that also underscored a current focus in the field of Jewish Studies: the scholarly inclusion of underrepresented segments of Jewish society.

“When the encyclopedia became available, we received calls questioning why Esther Kreitman, the Yiddish writer and sister of I.B and I.J. Singer, was not included in the work,” said Jeffrey Edelstein, the encyclopedia’s project director. “People thought it was because she was a woman. In fact, it was because Kreitman wrote in Belgium, not in Eastern Europe.” Although entries exist for Christmas and other aspects of non-Jewish culture in Eastern Europe, there are no entries for Peasants or Roma [Gypsies], two groups that undoubtedly shaped the daily lives and culture of Eastern European Jews.

“The encyclopedia, through the choices made for inclusion and exclusion, is unavoidably presenting a species of canon,” remarked Hundert. “This is, to say the least, not in fashion in the academy, and occasioned many debates among the editors.”

The project’s focus was, in part, biographical. The encyclopedia illuminates the complex world of East European Jewish artists, writers and intellectuals, as well as the re-ligious culture of Eastern European Jews. But such a focus did not preclude a look at the unusual and offbeat. In an entry for Binyamin Aharon Ben Avraham Slonik, for ex-ample, readers learn of a 16th century rabbi whose trailblazing efforts allowed for the deceased to be frozen, so bodies could remain unburied for more than the customary 3 days, in order for the proper identification of victims. He also allowed for “blind or ignorant people” to receive Torah honors. According to Nisson Shulman, a professor at Yeshiva University and the author of the entry, Slonik based many of his Jewish legal decisions on historical or medical knowledge.

But the encyclopedia’s contributors weren’t limited to tangible people and places; many entries tackle broad thematic topics. For example, in the entry for ‘Love’ we learn about how love was viewed by Ashkenazic Jews over time. (“The concept of romantic love was seen as foreign in East European Jewish culture, a society that relied on arranged marriages and carefully separated the sexes in its religious and educational institutions,” writes Naomi Seidman, the Koret Professor of Jewish Culture at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California. “The literary embrace of the power of love was tempered by a concern that romantic freedom would lead to intermar-riage…Love thus represented both the intricate tapestry of East European Jewish society and its most potent threat.”)

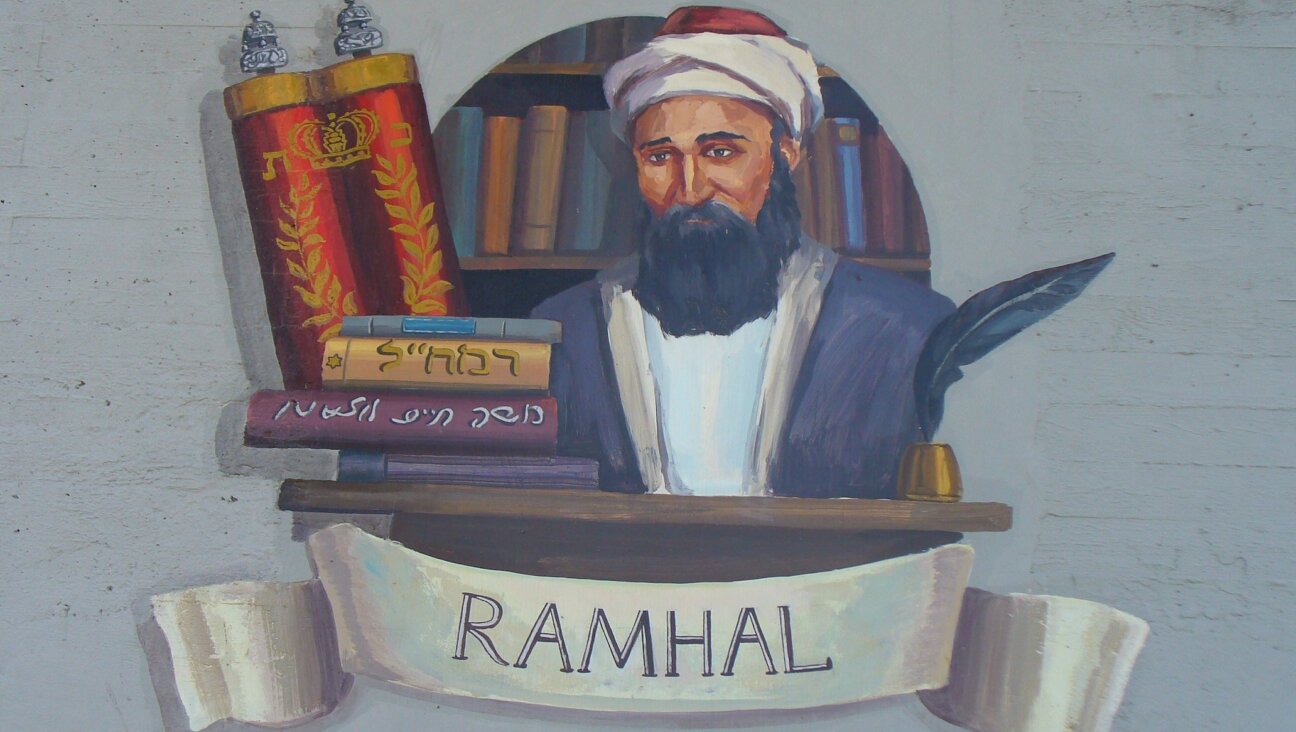

The encyclopedia also includes illustrations arranged in color plate inserts and throughout the volumes by editor Roberta Newman. The pages burst with striking black and white photographs and vivid fin de siècle paintings and stern Soviet Yiddish posters. “Can I also put in a word for beauty?” remarked Alice Nakhimovsky, a contribu-tor and professor of Russian and Jewish Studies at Colgate University. “So many of the illustrations here — including the color plates — have not been reproduced before, and certainly have not been seen together before. It is a pleasure to hold, and look at, and contemplate.”