Six Degrees of Treyf: An Interview With Gary Shteyngart

Gary Shteyngart’s new novel, “Absurdistan,” comes out May 9, published by Random House. And since Shteyngart is one of only two novelists who have made me laugh out loud in the past year, it seemed time for an interview. We met in New York City at one of his favorite restaurants, the Grand Central Oyster Bar. Shteyngart was hoping for the lobster BLT — “six degrees of treyf,” as he calls it. That wasn’t on the menu, so he happily settled for a spread of oysters: less interesting but equally far from kosher. And a bottle of muscatel, which got us thinking about drinking, which got us talking… — Mark Oppenheimer

Q: Is that vodka thing for real with Russians? Do Russians really love their vodka that much, or do you feel you have to drink it?

A: I worship vodka. It’s the best booze ever made. You know what “vodka” means? It’s a diminutive for water, so vodka is “little water.”

Q: Do you have siblings?

A: I don’t. Russians don’t breed in captivity. I’d like to. My girlfriend has two siblings.

Q: Let’s talk about your girlfriend.

A: She’s a young Korean American woman.

Q: Is she the one in the acknowledgments of the first book?

A: That was a different Korean American woman.

Q: You’ve obviously been accused of having a fetish, then.

A: Look, there was a Texan, an Armenian girlfriend in college…

Q: Has there ever been a Jewess?

A: Never a Jewess. I kissed one once — she tasted like me. I couldn’t take it.

Q: You found it narcissistic.

A: Incredibly! I said, “You know what? I’m just going to go home, make out by myself. I don’t need to pay for this dinner.” I’ve never conjugated with a Hebraio American. Anything could happen, but it would be very unlikely.

Q: Why?

A: I grew up in a very particular kind of environment, much different from most American Jews, who, I think, grew up in a kind of freedom…. The Hebrew school experience was so awful that it left no doubt in my mind that although I would have many Jewish friends — I live in New York, I’m a writer, I mean what the hell — I wanted to branch out in terms of relationships. And also, I do think it’s very interesting to have, if I was ever to breed, a child that has more than one culture….There are probably 30 different reasons. I don’t specifically go out there and say I won’t date one, but it never clicks the way it does with other groups.

Q: And yet you went to Hebrew school for much of your childhood, so you’re no stranger to Judaism. Tell me what that was like.

A: I went [grades] one through eight. Do you know how much smarter I would be if I’d gone to even the lamest public school? This was beneath learning. This was backwards. We were swinging backwards to the womb. It was insane. My father had math books sent from Russia so I could learn math.

From the horrors of Hebrew school, where I felt so unaccepted — so hated by these Jews, because I was Russian, because I didn’t wear the right shirt, because I was poor, because I read books — from that to go to Stuyvesant [High School], which was incredibly multiethnic! So I think that was a major part of it. But even there, I was more accepted by people who weren’t Jewish.

Q: You went to Oberlin College in Ohio. Did you know then that it would all work out, that you would be a published novelist?

A: I had no idea. Are you kidding? I thought I would fail miserably. I had all these plans, though. I thought I would be an urban planner, I would be a diplomat, I was going to be a — you name it. I was very high throughout Oberlin. But in the back of my mind, I was this hungry immigrant.

Q: You had an offer for your first novel, “The Russian Debutante’s Handbook” (first published in 2002, by Riverhead), before you even began Hunter College’s Master of Fine Arts program; the man who became your teacher there, Chang-Rae Lee, sent his agent the writing sample you’d submitted. What did you do to make a living between college and the arrival of writerly success?

A: Well, I was working all these nonprofit jobs, like my hero. They were hilarious. I worked for NYANA, the New York Association for New Americans — or Jew Americans, we used to call it. It was a resettlement for Russian Jews. Hysterical. I was in the dept of communications. “Try not to get drunk” — I had to translate that for them. “If you’re at a party, stay sober.”

Q: Let’s talk about your new book, “Absurdistan.” Like your first, “The Russian Debutante’s Handbook,” this one stars a Russian American in his 20s who goes to Eastern Europe, nearly gets killed, hangs out with hipsters and gets laid a lot. But the two books have a very different feel; they’re both your children, but they have very different personalities. How would you describe those personalities? Or, put another way, how is this book an advancement, artistically, over the first?

A: The first book was a young man’s novel in every sense. I was in my early 20s when I wrote most of it, and I hungered for the very things as my hero: acceptance, love, a piece of the pie. “Absurdistan” was written in my late 20s and early 30s. The need for acceptance, the questions of identity had faded by that point. But what was left was a new understanding of the world around me, and what I hoped for was a sharper, more critical vision. I traveled to my share of Absurdistans, and the feeling that our own country, the U.S., was increasingly becoming one influenced what appeared on the page.

Q: In “Absurdistan,” Misha Vainberg, aka Snack Daddy, goes from Russia to the USA, then back to Russia, then to the fictional land of Absurdistan, home of the forgotten Mountain Jews. I’m working on a theory about why he keeps going to more and more exotic places — something about how geographic dislocation helps the author write satire. Help me out here — am I totally full of it?

A: Well, it’s an interesting theory, but all these places don’t exactly seem exotic to me. They seem spent, tired, finished. Brazil — now that’s exotic!

Q: You like traveling?

A: I love traveling.

Q: See, I hate traveling. I always want to be home in front of my own television.

A: Oh, no. When I was a kid, we used to travel a lot to the former Soviet Union. In fact, the way “Absurdistan” came about, in part, is when I was a kid we went to Georgia, to a province called Abkhazia, which has now been totally torn apart by civil war, but back then it was like the Soviet Miami Beach. Leningrad is this frozen city, but I remember landing in Sukhumi, and it was like this paradise. Palm trees, amazing food — Russian cuisine can often leave a lot to be desired, but here you had mutton and lamb chops on a skewer! I was addicted. And the people were small and furry, like my father. I was always addicted to that part of the world, that absurd part of the world.

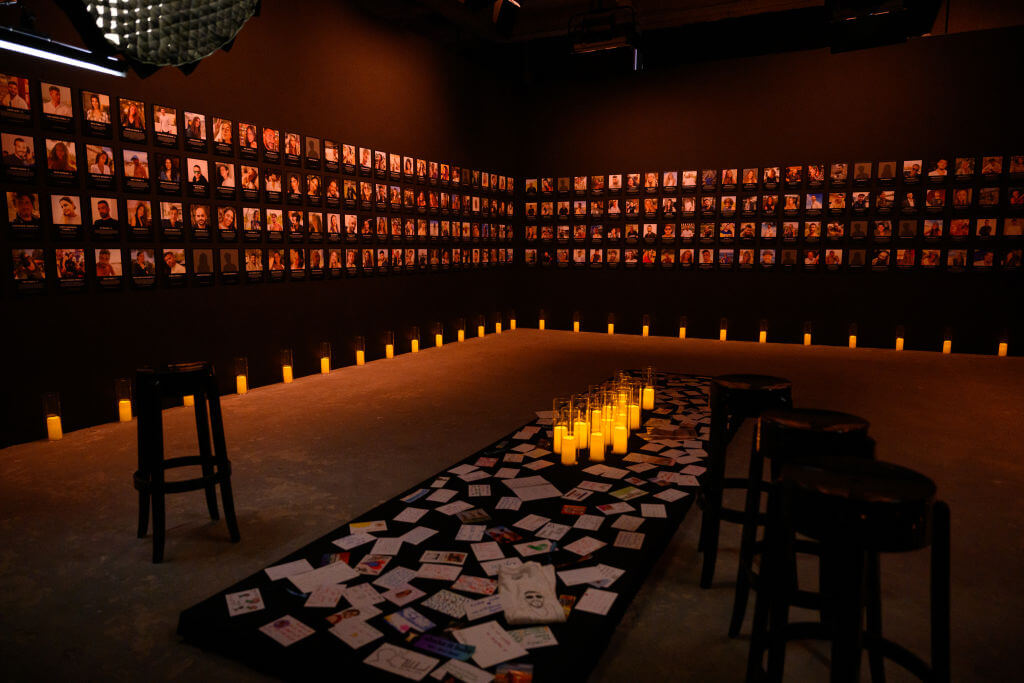

Q: At times, it feels as if “Absurdistan” is promiscuous in its satire — everything comes in for it, from Holocaust memorials [see excerpt below] to white guys who like rap to goatees. What is your main quarry? What do you most have in your gunsight?

A: I don’t really feel that I’m out there with a gun, hunting things down. The only thing I truly apologize for is the blatant goatee-abuse. I just got rid of mine, and I’m feeling frisky.

Q: Misha, like Vladimir in the first novel, is unmistakably Jewish. But, as in most “Jewish” novels, there is very little Jewish ritual. The Judaism is entirely cultural.

A: Oh, I disagree. At the heart of “Absurdistan” there is a very Jewish ritual — the penile disfigurement of Misha at the hands of the Hasids, something I am not unfamiliar with myself. That episode articulates my views on religion quite clearly.

Q: In this novel, you invent an alter ego, Professor Jerry Shteynfarb, who in fact steals Snack Daddy’s girlfriend. Why the alter ego? And will he be your Nathan Zuckerman in subsequent novels?

A: I love Shteynfarb, think he’s a good way of keeping things in perspective. And yes, he will be back, quite possibly in the next novel.

Q: Shteynfarb’s nemesis, Snack Daddy, is something of a rapper. Are you a rap fan?

A: At Oberlin, rap saved my life. It was the most liberating thing I’d ever encountered. He now seems like a dinosaur, but Ice Cube! These antisemitic, anti-Asian, anti-white, anti-everything raps. My homies and I would smoke that 6-foot bong and put him on, and it was the one really transcendent experience of my life, when I really felt at ease with myself. Because of all of this intellectualism and and immigrant striving — what the hell did I know about Compton and South Central? But for a second I thought I was really in a different world. An unhappy world, obviously, but it felt so familiar and so alien at the same time. It was the most enjoyable experience I ever had.

Q: I love your novels. But it’s obvious that what you’re trying to capture is a certain lack of rootedness. And the writers that I keep on my special shelf are these people with an intense sense of rootedness, like Evan Connell writing about Kansas City or John Updike writing about small-town Massachusetts.

A: Or maybe Philip Roth.

Q: Or maybe Roth, sure, writing about New Jersey. Nobody today seems to do what, say, Richard Russo does — just move to upstate New York and sit there. I am seeing so little of that.

A: It’s very curious you would say that, because after Bush won — won number two — there was this huge, collective “What the hell?” And I almost thought, “Should I go out in the red states and figure this s—- out?” Live in a small town, maybe teach. So the first thing I did was take the Canadian citizenship test.

Q: Did you really?

A: Oh yeah. It’s very easy. If you speak one of the two languages, have a master’s, or something else. I also looked up Web sites for Southern Dakota Community College to see what it would be like to live among those people. But the idea I came up with is actually to write my next book partly in Albany — but set in the year 2040, when it’s called All-Holy Albany Rensselaer, and it’s a small religious protectorate under the command of a Korean Rev. Cho. My hero, Jerry Shteynfarb, is 65 years old, married to one of Reverend Cho’s daughters and trying to eke out a survival. That’s going to be the next project.

Q: Who are your favorite writers?

A: Dead: Roth — oh, that was the biggest Freudian slip ever! But I just read the galleys for his next book. It’s the most depressing thing I’ve ever read. But it’s amazing.

Q: I feel he should break into Toni Morrison’s house and steal her Nobel Prize.

A: It’s totally unfair. I hope it will be remedied before he croaks.

Q: It won’t.

A: Going back to the dead. Nabokov. Nabokov for the style, Roth for the Jewish family. Okay, again, back to the dead: The 19th-century Russians. I do think that was the golden period. It was immaculately written. It was the combination of part documentary and part journalistic. Turgenev’s “Fathers and Sons”— it’s like Tom Wolfe without the ridiculous pretensions.

Q: You grew up in Queens, but you now live on Grand Street. Why did you move to the Lower East Side?

A: I love the Lower East Side more than anything. I spent five years on Clinton Street, and I was living in this sixth-floor walkup with roaches you could arm wrestle with. When I was there, we were “los blanquitos,” the white guys. Now, the Dominicans are getting pushed back to the projects. [Still,] I live in one of the few nonmillionairized neighborhoods of Manhattan. I look out on a series of projects, occasionally some gunplay. And my neighbors are wacky — it’s the Hispanics, the hipsters, and the Hasids. You gotta have that.

Q: What would be fun is to find someone who’s all three. A Hispanic hipster who’s become a Hasid.

A: That would be a whole issue of the Forward.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture How one Jewish woman fought the Nazis — and helped found a new Italian republic

-

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

-

Fast Forward Betar ‘almost exclusively triggered’ former student’s detention, judge says

-

Fast Forward ‘Honey, he’s had enough of you’: Trump’s Middle East moves increasingly appear to sideline Israel

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.