The Problem With Liberals

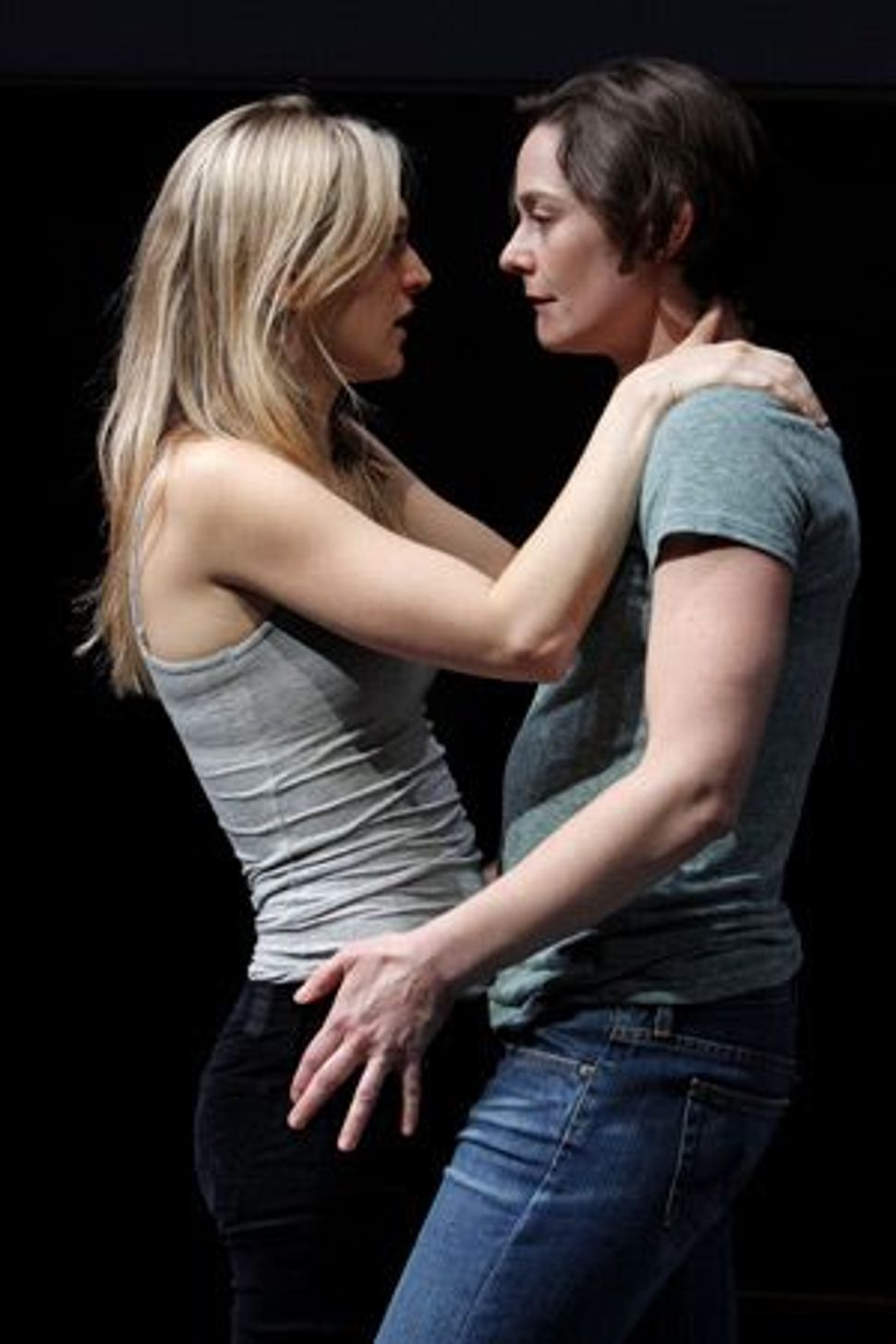

A Pundit?s Affair: Ellen (Marin Ireland, left) ditches schoolteacher Danny for experimental filmmaker Amy (Jenny Bacon). Image by JOAN MARCUS

There was a time, in the 1980s and early ’90s, when kitchen-sink realism was so ubiquitous that it seemed this was the only “correct” way to write a play. You place your usually working-class characters around the dining room table, or maybe the living room couch, and let them talk at each other, slowly unveiling their secrets and betrayals, until, a couple of hours later, some emotional truth has been uncovered. These plays usually consisted of composites, in the Chekhovian vein, of characters who, if the play worked, were all so alive and nuanced and individual that the audience felt like they were spying on actual people living their actual lives.

More often than not they didn’t work, though. They were too self-conscious. The form had by then become so codified that the manipulations of the authors as they jerked their characters toward the requisite touching reconciliation (or bittersweet separation) overpowered any true insights the plays might have about the lives of the people shuffling around onstage.

I thought about this now thankfully long-gone moment in theater history while watching the Public Theater’s production of “In the Wake,” a new play written by Lisa Kron and directed by Leigh Silverman, not because this play is kitchen-sink realism — it’s not, or not exactly — but because it is an example of another, more current trend in the theater not wholly unrelated to kitchen-sink realism. Let’s call it subjective realism, the play as psychodrama pursuing some Joycean epiphany. The main difference between this sort of play and its antecedent is that periodically, betwixt and between the scenes, the protagonist addresses the audience, framing how we’re supposed to look at and understand what we’re watching. Thus as we’re led through the play, we’re firmly rooted in, and rooting for, a single character about whom we have privileged knowledge, and presumably, with whom we’re meant to identify.

Kron’s previous plays, “Well” and “2.5 Minute Ride,” focused on her complicated Jewish identity: her mother who was born Christian, and her father’s Holocaust decimated family. The character in “In the Wake” whose journey we’re following is Ellen, a liberal firebrand, educated and open-minded, and consumed by her rage at Republicans in general and George W. Bush in particular.

As played by Marin Ireland, Ellen comes across as a fair representation of a certain New York type, whip smart and stylish and a little daffy, driven by her intellect and convictions, intimidatingly capable of articulating and acting on her beliefs — the sort of person the typical New York theatergoer might in fact identify with, or, anyway, ideally want to be. Her problem, as she describes it to the audience, has to do with “blind spots” and the devastation they might wreak on her life, and from early on we’re led to understand that over the course of the evening we’ll see what she means.

In a sort of corrective to the ludicrous version of New York life depicted on the TV show “Friends,” Ellen lives in a cramped, randomly furnished fifth-floor walkup with her public school teacher boyfriend, Danny (Michael Chernus). The two of them spend nearly all their time hanging out and horsing around with Danny’s sister, Kayla (Susan Pourfar), an office slave who dreams of becoming a writer, and Kayla’s tomboyish wife, Laurie (Danielle Skraastad). They’re all lefties, to various degrees, but mostly they’re young people struggling with the limits of their lives.

Only Ellen is defined by her politics. Sometimes, her friend and kinda sorta mentor, Judy (a riveting, white-hot Deirdre O’Connell), shows up like an alien and stays with her between aid-work gigs in the most war-ravaged regions of Africa. When Ellen and Judy are alone, the play takes on a deeper, darker color. Gone is the light, zany 20-something banter. In its place, we’re given depth of character. Deirdre O’Connell’s Judy is a woman of frightening, heartbreaking bitterness — a wise old warrior, so radically outside the American mainstream that she seems to exist in different reality from the one the other characters inhabit.

Kron allows the characters room to play onstage, and her dialogue has wit and bite to it; it’s alive to our times and to the people living in them.

The action in the play is mostly reported upon, embedded almost incidentally in the scenes, much the way action transpires in kitchen-sink plays. We pop in on the characters and watch them live through various flashpoints in the political topography of the early 2000s — the Thanksgiving of the hanging chads, the day Al Gore conceded the presidential election, 9/11, the day of the worldwide march against the invasion of Iraq, etc. And, periodically, Ellen steps forward to guide us through the story and to remind us that we’re meant to empathize with her.

Ellen rises from political junky to writer and pundit, the sort of person who gets profiled by The New York Times and flies off to speak at conferences across the nation. She begins an affair with an experimental filmmaker named Amy (Jenny Bacon). Danny, whom she tells about the affair, is kindhearted and tolerant; he uses understated Midwestern humor to deflect his pain. Kayla and Laurie disapprove of Ellen’s Sapphic betrayal, but because they love Danny and he claims to accept the situation, they hold their tongues.

We know where this is going. And it’s not going to end well for Ellen. The problem is that, despite the structural guides, we’re no longer on Ellen’s side; she’s too self-centered, too much of an emotional bully, taking and taking and never giving. And because of the way Kron has situated Ellen as an avatar for the audience, putting her in the spotlight on the darkened stage and allowing her to explain her feelings and internal conflicts at length, if we stop caring for her, we won’t experience the catharsis that subjective realist plays of this sort require if they’re to succeed.

This is not so much a failure of Kron’s talent — her humor, her fire, her complex understanding of sociopolitical realities and how they sometimes wound the human animal are all vividly present in “In the Wake” — as it is a failure of the essentially sentimental form through which the writer has chosen to tell her story. If Kron’s structure were less reliant on the audience’s sympathy toward the protagonist, her play might have contained room for the ugliness and complexity of character in which she seems in the end to be interested. But sadly, this sort of subjective realism is jerry-rigged toward flattering the audience, leaving no room for the problematic contradictions that make us human.

Joshua Furst is the author of the novel “The Sabotage Café” (Knopf, 2007) and the collection of stories “Short People” (Vintage, 2004).