She’s Scot Game

Celtic and Jewish music and dance traditions are rarely compared, and even more rarely combined, but the upbeat circle dances of the Celtic ceilidh have much in common with the hops, kicks and turns of the hora.

And in the music of the harp-and-fiddle duo Tzalool, which fuses Celtic and Jewish rhythms, the parallels are on full display.

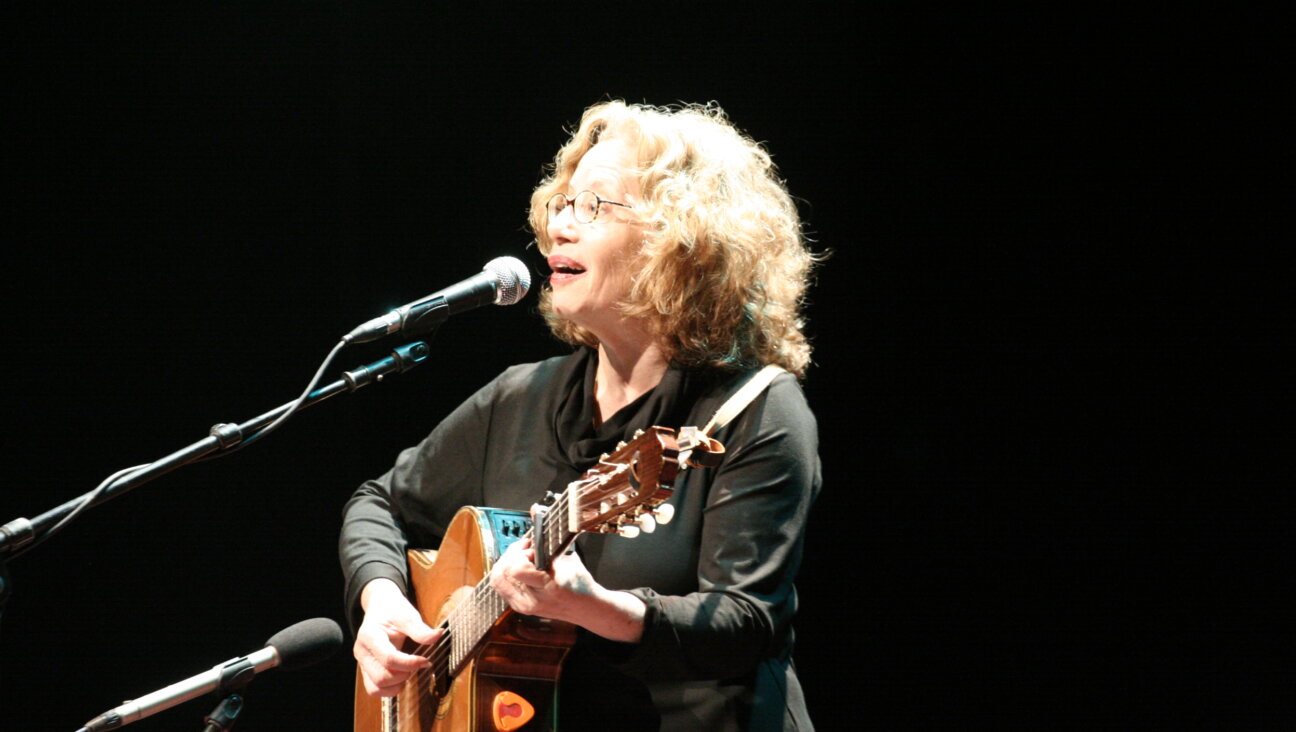

“Both traditions have this idea of really soulful music, and they also have dance music,” said harpist Sunita Staneslow. Staneslow and fiddler Gal Shahar arrange and improvise most of their own material, and last year released their first CD, “Are You at the River?” Tzalool performs regularly in Israel, where Shahar grew up and where Staneslow, originally from New York, moved with her family in 2000. The duo will be making appearances at a number of Canadian music festivals this summer.

For Shahar, the similarities between Jewish and Celtic styles lie less in the music itself than in “the spirit of bringing people together” that animates both traditions.

While Jewish and Celtic musical traditions don’t share much in the way of history, the blend was a natural choice for the two musicians, both of whom have deep connections to Celtic music. Staneslow, whose husband was born in Edinburgh, plays a Scottish harp. A graduate of Manhattan School of Music, she is, like many harpists, trained in classical music. But it was her interest in folk and Jewish music that inspired her first cassette, “Celtic With Klezmer,” in the late 1980s.

Shahar says there was little Celtic music in Israel when he was growing up, but it was the simple melody of “Loch Lomond,” which a violin teacher assigned him at the age of 8 or 9, that really inspired him to practice for the first time. For Shahar, who eight years ago founded the Celtic ensemble Evergreen with four other Israeli musicians, a love of Celtic music was deep and immediate. Only recently did he begin feeling the same connection to Jewish music, which, growing up, he’d seen as the exclusive province of the Orthodox.

One of the pieces in the Tzalool repertoire, “In Between the Sounds,” was written by Shahar’s wife, Michal, and inspired by a Celtic-Jewish interaction from the fiddler’s family’s history. In the 1930s, Shahar’s future father-in-law lost his father. To help cope, he would sometimes skip school and spend his days in the forest near Jerusalem, where he met a Scottish soldier who used the forest for bagpipe practice.

“He didn’t know English at the time; the Scotsman didn’t know Hebrew at the time,” Shahar said. “So there was a relationship without language.” But the bagpipe music helped Shahar’s father-in-law deal with his grief. “It went through his pain and dispersed it.”

In performances, the duo usually follows “In Between the Sounds” with a Scottish reel.

Staneslow and Shahar are unique not just in the types of music they play but also in the instruments they use. King David played both the harp and the fiddle, but the two instruments seldom have appeared together since — even though working with a fiddler gives a harpist the rare opportunity to play melodies in addition to harmonies.

Nor has the harp had much of a role to play in Jewish music. “Not everybody knows the word [‘nevel,’] ‘harp’ in Hebrew,” Staneslow said. The most famous Jewish harpists, including Harpo Marx, did not play Jewish music.

But that appears to be changing. Therapeutic harp music has recently come to Israeli hospitals — Staneslow works as a harp therapist each week at the Schneider Children’s Hospital near Tel Aviv — and a recent grant will also bring two harpists to a hospital in Jerusalem. (The harp is ideal for therapy, Staneslow said, because the instrument’s vibrations “can feel like a blanket of sound… there is something naturally soothing about the tension and release of a plucked string.”) Three new harp builders have begun working in Israel over the past decade. In 2006, an Israeli, Sivan Magen, won Israel’s International Harp Contest for the first time. Most of the contest’s previous winners had hailed from Europe.

“There’s little sprinkles of people… bringing the harp back as a Jewish instrument,” Staneslow said. “It’s only just beginning, and I hope it’s something that really grows.”

Staneslow and Shahar are trying to help the process along.

“Maybe 50 years ago it couldn’t work together,” Shahar said of the duo’s Celtic-Jewish sound. “But today it can.”

Sara Polsky’s writing has appeared in Poets & Writers, The Hartford Courant and other publications.