Intrepid Guide Takes You to Territories

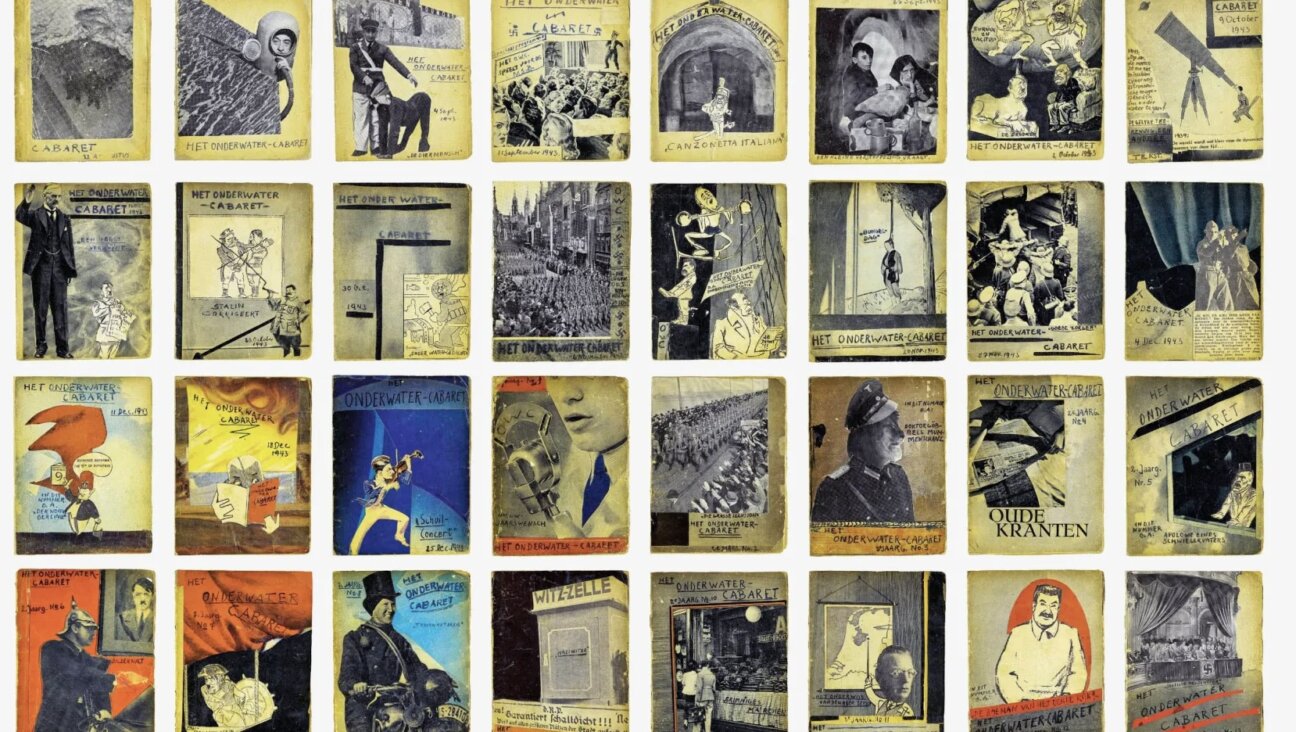

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Not in Kansas Anymore: Tour guide Fred Schlomka takes tourists to refugee camps and West Bank towns to expose a rare glimpse of Palestinian life under occupation. Image by sunita staneslow

Fred Schlomka is quite an extraordinary man, and his travel company, Green Olive Tours, is built to match. Working from his small home in Kfar Saba, a suburb of Tel Aviv, he operates a network of a dozen Israeli and Palestinian guides who take tourists deep into the Occupied Territories, from Nablus and Jenin in the north to Bethlehem, Hebron and the Dead Sea in the south. On a Green Olive Tour, you are as likely to have lunch with a settler as you are to spend the night in a Palestinian village. You may see the usual historic sites, but you will also be shown the separation barrier and get briefed on the latest human rights situation under the occupation.

This brand of tourism has earned him a hostile grilling from the Israeli Tourism Ministry, and Schlomka claims that the Israel Hotel Association has sent out a memo warning hoteliers to look out for his leaflets and get rid of them. He is determined to make a success of his small but growing company, however, and his life story suggests that he is not a man to be easily diverted.

Fred Schlomka Image by sunita staneslow

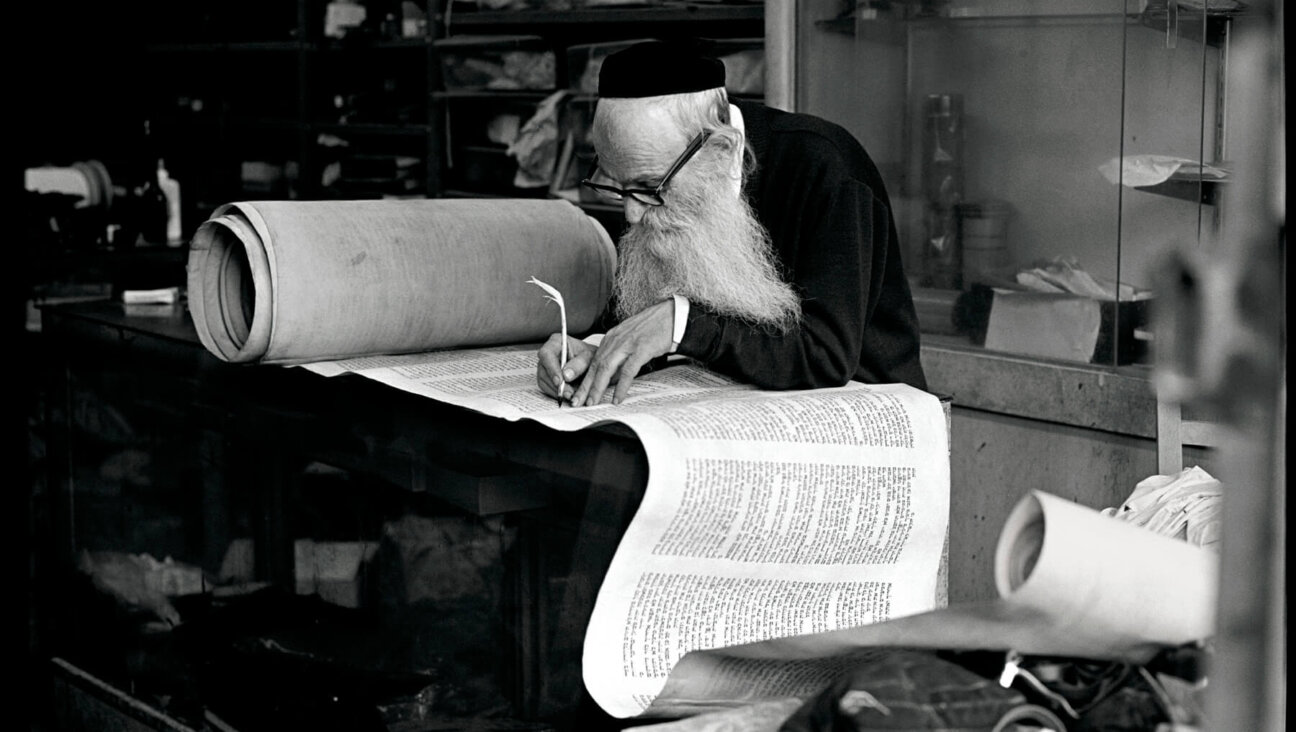

Schlomka’s father arrived in Israel in 1936, having been tortured by the Nazis as a communist agitator, after which he fled Germany while on bail. There, he married a native Israeli, from Jaffa, and they had their first child, Fred’s elder brother. His father remained politically active but, disappointed by the noncommunist nature of the emerging Israeli state, and fearing for the welfare of his young family in a nation at war, the Schlomkas left in 1948, settling in Scotland.

Fred was born in Edinburgh, where his father opened a bookshop. The after-effects of his torture continued to trouble the elder Schlomka, and when Fred was only 3, his father died. The deep misfortunes of Schlomka’s early life continued to deepen, with his mother soon succumbing to a nervous breakdown for which she was sent to an asylum. Fred and his two elder siblings were declared orphans, but when Nazi reparations began to be paid, providing an income, it was decided that the three children, all younger than 10, would be placed in a flat under the care of a series of “housekeepers.”

Of one housekeeper, Mrs. Knox, Schlomka recalls simply, “Her behavior was wicked.” Schlomka and his siblings were verbally and physically abused by Mrs. Knox, several of her predecessors and also a legal guardian to whom they were sent for “discipline,” which often involved sequences of freezing and scalding baths. When Schlomka was 8, he arrived home from school to be told that his brother was dead. He and his sister were not allowed to attend the funeral, and only sometime later were they told that their brother had committed suicide.

Schlomka describes the remainder of his childhood as semi-delinquent. He ended up at a boarding school in the Scottish Highlands, Lendrick Muir, which had been created for, Schlomka explained, “emotionally maladjusted children of above average intelligence.” He left having passed only two exams, and as soon as he could, he exited the country with a school friend.

He and his friend eventually ran out of money in Almería, a city in southern Spain’s Adalusia. They spent their last few pesetas on some colored string, and began to make and sell macramé jewelry. Soon the jewellery became a craze; they were selling everything they could make, and staying in hotels. Schlomka has been an entrepreneur ever since.

Schlomka has worked in various capacities — as a carpenter, brick-maker, busker and building contractor in Europe, America and New Zealand — but in the early 1980s he began to visit Israel more frequently, seeking out his mother’s family, a large clan of Tel Avivians. Within three months of meeting Sunita Staneslow, who was at that time the principal harpist in the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, the two were married.

In 2000, after stints in Israel and America, Fred, Sunita and the couple’s children finally made aliyah. Schlomka’s work in Israel soon took on a political bent. For two years he was the operations manager of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, and for another two years he was behind a project attempting to build mixed Arab/Jewish communities in Israel. When his work in nongovernmental organizations led to him conducting tours of the West Bank for activists, journalists and diplomats, he decided to set up a company offering this service on a more formal basis, giving tourists the opportunity to see places that other Israeli tour companies actively discouraged them from visiting. “You have to see it to understand it,” he said.

What becomes clear when you are in the hands of one of Schlomka’s guides is that just to see what is happening in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, an outsider needs expert assistance. Negotiating checkpoints and segregated roads is complex enough, but even harder to penetrate is the cosmetic veneer placed around the structures of occupation, which make it easy for Israelis not to see what is happening under their noses. Land banks, tree planting, carefully routed roads and even aesthetic stone cladding mean that with an Israeli number plate, you can drive to settlements deep inside the West Bank without feeling that you have left the suburban sprawl of the major Israeli cities. The separation barrier, that 25-foot edifice of concrete that is a daily feature of life for so many Palestinians, is all but invisible.

Only under the guidance of someone like Schlomka is one likely to see both sides of the Occupied Territory, and to see firsthand the astonishing contrasts that abide so close together. I spent one night with the Feldstein family in the comfortable and prosperous settlement of Efrat, being told that it’s not a problem living close to the separation barrier because “we had walls like that along the freeway in New Jersey, and we called them sound barriers.” Two days later, I was in the Palestinian village of Beit Ummar, where an army roadblock had sealed the entrance to the village, a funeral had been tear gassed the previous day and, one night earlier in the week, settler youths had raided the town, burning three cars.

A week in the hands of Green Olive Tours provides a degree of insight into the occupation that no amount of reading could ever provide. For those with less time to spare, any one of the company’s scheduled half-day tours will provide a fascinating antidote to the usual narrative. Schlomka may not be a popular man at the Israeli Tourism Ministry, but he is adamant that the only way to understand is to see, and as long as he is taking people into the West Bank, he is doing good work. Schlomka’s passion for understanding and cross-cultural communication is indeed hard to resist; coming from a man with his blighted past, one could go so far as to call it inspirational.

William Sutcliffe is the author of five novels, most recently “Whatever Makes You Happy” (2008, Bloomsbury USA)