Aussie Novelist Takes on Civil Rights

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The Street Sweeper

By Elliot Perlman

Riverhead Books, 617 pages, $28.95

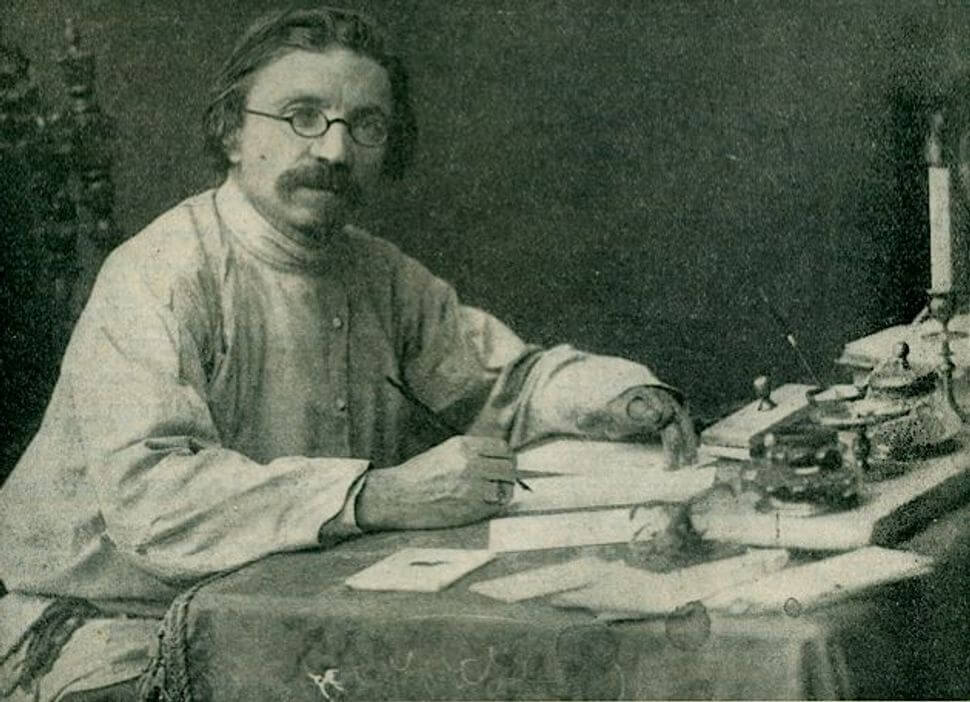

The book that turned Elliot Perlman into a writer was the only book in the house that his liberal mother didn’t want him to read. Her reasons were pragmatic, not philosophical: As a high school English teacher, she was preparing “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” and told him not to touch the books on her bedside table.

Elliot Perlman Image by david cook

That was reason enough for a cheeky 11-year-old to pick up Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s powerful indictment of the Soviet Gulag and discover that books could be both morally and emotionally compelling. It was a far cry from the British children’s stories that were standard reading fare for an Australian boy in the 1970s:

I hated them because they were boring. Five go up a tree. Five go down a tree. Make lemonade. I don’t care. Then I read ‘The Life of Ivan Denisovich.’ On page one there’s a man in his cell trying to catch a bug so he can eat it for extra protein, and I thought, ‘Wow, you can write about this stuff.’ An 11-year old kid was entranced to discover you could write about eating bugs and they would give you a Nobel Prize.

But it’s the moral passion of Solzhenitsyn, not the bug eating, that made Perlman a novelist, and his deeply Jewish sensibility and liberal politics are never so evident as in “The Street Sweeper.” It’s a vast tale of history and humanity that encompasses both a vividly original Holocaust perspective and a story of blacks and Jews in the civil rights movement.

“The Street Sweeper” is a big novel in every sense. The history it encompasses is weighty, its moral compass broad, the stories multiple and the page count large. It’s filled with color and characters whose unlikely connection tells the stories of contemporary New York, 1930s Warsaw and 1950s Chicago.

Perlman was raised in Melbourne, Australia, and we met in a local cafe since he was back home after an extended period first commuting to and then living in New York, an experience he says gave him the chutzpah to write a very American story. In fact, his New York home was directly opposite Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, where he brings together two key characters: Lamont, an African-American janitor, and Mr. Mandelbrot, a Holocaust survivor and cancer patient.

He explained the origin of the novel: “On the bus I’d overhear conversations between people of every background, race, class, and it fired that novelist’s question: What would happen if an unlikely friendship were to blossom between two people who should never meet?”

In the dedication to “The Street Sweeper,” Perlman characterizes black victims of racist violence and Jewish victims of the Holocaust as suffering from “different manifestations of the same disease.” Weaving together their stories meant exploring the complex history of black-Jewish relations. He learned about Jewish lawyers and “red diaper babies” involved in the civil rights movement but, on the other hand, he discovered that many Southern Jews of the time kept their heads down. He learned how relations between the black and Jewish communities soured in 1968, when Jewish teachers’ union officials went head to head with a black parents’ group in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville area of Brooklyn.

But if telling the American civil rights story required massive research, that was nothing compared with the effort needed for Perlman to be able to tell the Holocaust history. Although his family left Europe before the war, Perlman grew up with the Holocaust in focus. The family joke was that his father was the only Holocaust survivor who had never left the Melbourne Jewish suburb of Carlton; he was an Australian who felt deeply the suffering of the European Jews. At Perlman’s Jewish high school, many of his friends were children of actual survivors, and some of the teachers had numbers on their arms.

While researching “The Street Sweeper,” Perlman visited Auschwitz six times and broke down during each visit.

It was kind of brutal but I kept thinking I should shut up and suck it up because it’s part of my job and it’s nothing compared to what these people went through. So it’s self-indulgent of me to go as a tourist and then back to my lovely hotel and have a nice meal and even to be friends with my guide and meet his family. And when I got sick they took care of me and brought me honey-flavored vodka. This is not the experience of a Polish Jew in the ’40s.

There have been, of course, thousands of Holocaust novels, but Perlman did not doubt that he had a new story to tell, both because of the diverse layers of experience he brings to refract the content and because of the voice he gives Mandelbrot as a rare survivor of the Sonderkommando, the Jewish prisoners forced to work inside the gas chambers. This perspective allows Perlman to take the reader inside the gas chambers, recounting in meticulous detail the mechanics of mass murder.

Survivor stories are, by definition, the stories of those who did not go to the gas chambers. But their Holocaust experience is not typical, because between 70% and 100% of each transport went straight to their deaths. The few Sonderkommando who survived were the only Jews who saw exactly what happened in the gas chambers and lived to bear witness.

“The reader can’t go there normally, because it’s unbearable. If you have a character that you have a connection with and you see that the novel ends, and you only have a page or two left and the character is in the gas chamber so they are going to die, you can’t bear it,” Perlman said. “But what gives comfort to the reader in ‘The Street Sweeper’ is that the man telling you about his experience in the gas chamber is alive in Memorial Sloan-Kettering in the 21st century, and so the reader knows, as terrible as it all is, the person I’m with didn’t die, and that helps the reader get through it.”

Perlman’s novels are meticulously planned, and the narrative structure also gives the reader relief from the trauma of dragging corpses out of the gas chambers. The novel switches frequently between different stories set in different times and places, but with enough connections between characters to build a big picture tale, too. In multiple parallel stories, we move among an ex-con trying to rebuild his life, an academic losing his grip and a single father coming to terms with an impossible history. Together they confront questions about history, memory and loyalty, as well as economic and social justice.

Perlman is aware that his political and social views are apparent in his writing and that he must use his craft to avoid being didactic. His first novel, “Three Dollars,” published in 1998, was a sharp portrayal of a victim of economic rationalization, and his next, “Seven Types of Ambiguity,” in 2004, critiqued empty relationships and obsessive materialism within a psychological thriller. Both were short-listed for or won prestigious Australian literary awards, and “Three Dollars” was made into an award-winning film.

With “The Street Sweeper,” he was drawn to the story rather than to the social agenda. But the progressive politics come naturally to him. He grew up in a leftist home and was surprised as an adolescent to discover that not all Jews were like that. By showing how historical trauma and shared experiences can feel different through various racial, ethnic and religious perspectives, he hopes that the different communities will understand one another a little better. It seems a fitting way to end his New York period.

Deborah Stone is an Australian journalist and a former editor of the Australian Jewish News.