‘Stars of David’ Becomes a Musical

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

When Abigail Pogrebin decided she wanted to interview Jewish celebrities about their Jewish identity, even her husband was skeptical.

“I think it’s a great idea, but why would anyone talk to you?” he told her.

“I basically dove in with a prayer,” said Pogrebin, a Manhattan-based journalist and former television producer. She began with her own contacts: her onetime boss at “60 Minutes,” Mike Wallace; family friend Gloria Steinem; Leonard Nimoy, who had attended Torah study with her parents; Sarah Jessica Parker, whose husband, Matthew Broderick, had gone to Pogrebin’s grade school, and Wendy Wasserstein, who knew her literary agent and her twin sister, Robin Pogrebin, a New York Times reporter.

Some 62 interviews later, Pogrebin had her book, “Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish” (Broadway, 2005). Divided into short chapters, it is an unexpectedly intimate compendium of thoughts about observance, heritage, family and the State of Israel, by such luminaries as comedian Joan Rivers, playwright Tony Kushner, actor Jason Alexander, writer Aaron Sorkin and Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The book went into eight hardcover printings and paperback — and is now a musical, “Stars of David,” which runs through November 18 at the Philadelphia Theatre Company’s Suzanne Roberts Theatre.

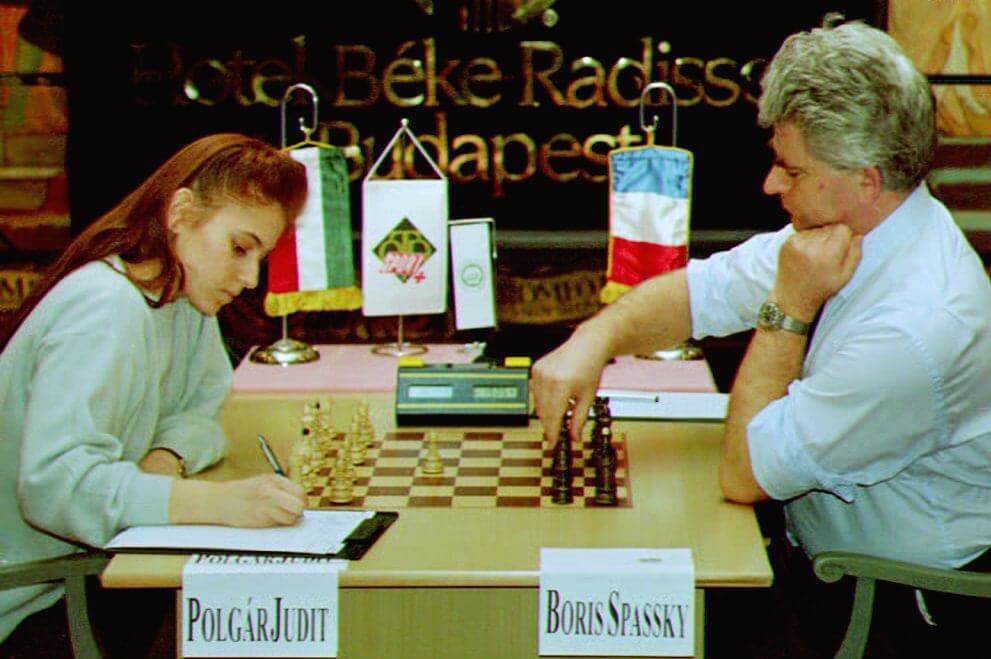

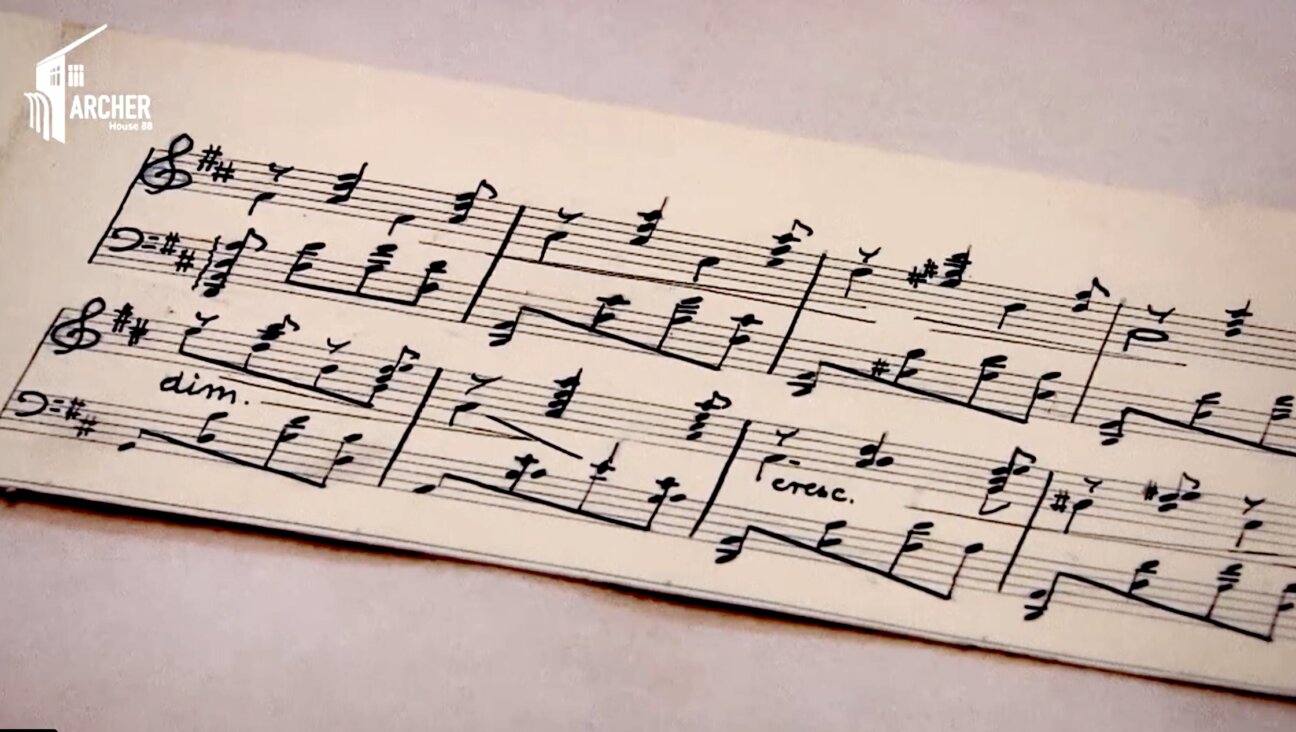

Written by Charles Busch (“The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife”) and directed by Gordon Greenberg, the show features songs by an astonishing assemblage of Broadway talents, including William Finn (“Falsettos”), Tom Kitt (“Next to Normal”), Duncan Sheik and Steven Sater (“Spring Awakening”), Marc Shaiman (“Hairspray”) and Sheldon Harnick (“Fiddler on the Roof”). Marilyn and Alan Bergman (“Yentl”) collaborated with composer Marvin Hamlisch to musicalize their own interview, one of Hamlisch’s last works before his death in August. Broadway veterans Brad Oscar (“The Producers”) and Joanna Glushak (“Hairspray”) lead the five-person cast.

The concept for the musical came in 2008 from Aaron Harnick, Sheldon Harnick’s nephew and yet another Pogrebin family friend. “I was sort of stunned by the idea at first,” said Pogrebin, whose own musical theater roots include a role in the doomed original Broadway production of Stephen Sondheim’s “Merrily We Roll Along.”

But Pogrebin said she decided that the interviews had “a certain dramatic arc” and reflected universal struggles — “this idea of what do you belong to, what do you have to carry on, what is tradition in your life, and does it matter?”

Pogrebin detailed her own Jewish journey in the book’s epilogue. Like many of the celebrities she interviewed, she was only casually observant when she began the project. But her discussion with Leon Wieseltier, The New Republic’s literary editor, and his denunciations of “slacker” Jews and Jewish ignorance about Judaism shook her. “That was the game-changer, that interview,” she said. She began Torah study and ended up, at age 40, celebrating her bat mitzvah.

Busch, the musical’s book writer, took Pogrebin’s story as the starting point of a narrative through-line and fictionalized it. Harnick and Greenberg (who had helped musicalize Studs Terkel’s oral history, “Working”) recruited songwriters to create musical portraits of various characters. Pogrebin secured permission from her interviewees and forwarded them lyrics for comment and approval. Ginsburg penciled “really specific” notes in the margins, Pogrebin recalled.

In approaching songwriters, Busch said, “we basically gave no guidelines at all.” Instead, they were told, “Do whatever intrigues you, however you want to do it, in whichever style you want to do it.”

When it became clear that the songs could not be fitted “into some already written script,” Busch said, he and Greenberg “took index cards with the name of each song and put them on the floor, and rearranged them to see what kind of narrative naturally evolved.”

The creative team’s aim, Greenberg said, was “to capture the intelligence and the humanity of this book that is highly relatable — certainly for Jewish people, but really for anybody who is questioning the value and the resonance of their cultural and religious identity.”

Kitt, the Tony Award-winning composer of “Next to Normal” (and co-creator of the current Broadway musical “Bring It On”), joined the project and began writing songs with Pogrebin as his lyricist. Eventually, Harnick decided that “Stars of David” “should become a huge collaborative project rather than one composer trying to tackle all of these stories,” Kitt said. (According to Busch, Sondheim, who was interviewed for the book, was one of the few who demurred.)

Why did so many star songwriters participate? “When you look at the list of people, you think, ‘I’m kind of honored to be asked to be part of that group,’” Kitt said.

Just as writing the book did for Pogrebin, working on the musical inspired many of those involved to re-examine their Jewish heritage and identity.

“For the very first time in my life I went to Kol Nidre services, two weeks ago,” Busch reported. “It was very beautiful. I was very moved by it. It was exhausting, though. Do the Jews always have to stand up the whole time? Oh my God, I was getting sciatica.”

Greenberg’s reaction was different. The show encouraged him to examine “what are the cultural references that I owe to the way I was raised, and what subconsciously may have drifted in through osmosis without me even realizing it.

“For me, the idea of being Jewish goes well beyond actual observance and Jewish ritual. It has to do with something that’s cultural, something that’s a sensibility or an aesthetic.”

What he finds “inherently very Jewish — and very American” is “the whole idea of that open door — the notion that the thing that keeps a culture or religion alive is questioning, the debate, opening it up, airing it out, exploring it, never taking it for granted.”

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia and a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review.