Finding Tale of Redemption at Auschwitz

The Book Thief: Jon Clinch, author of ??Finn,? decided to go the self-publishing route with his second novel, ?The Thief of Auschwitz.? Image by Courtesy of Jon Clinch

The Book Thief: Jon Clinch, author of ??Finn,? decided to go the self-publishing route with his second novel, ?The Thief of Auschwitz.? Image by Courtesy of Jon Clinch

By Jon Clinch

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 276 pages, $16

‘The Thief of Auschwitz” stole my sleep.

Jon Clinch’s latest novel, which he has chosen to self-publish, is a page-turner with style. It’s a simpler, quicker read than “Finn,” his impressive first novel, which brilliantly imagined the backstory of Huckleberry Finn’s brutish father.

Here, Clinch offers two interlocking tales: a third-person account of the travails of a Jewish family in Auschwitz, and the first-person musings of the surviving son in old age.

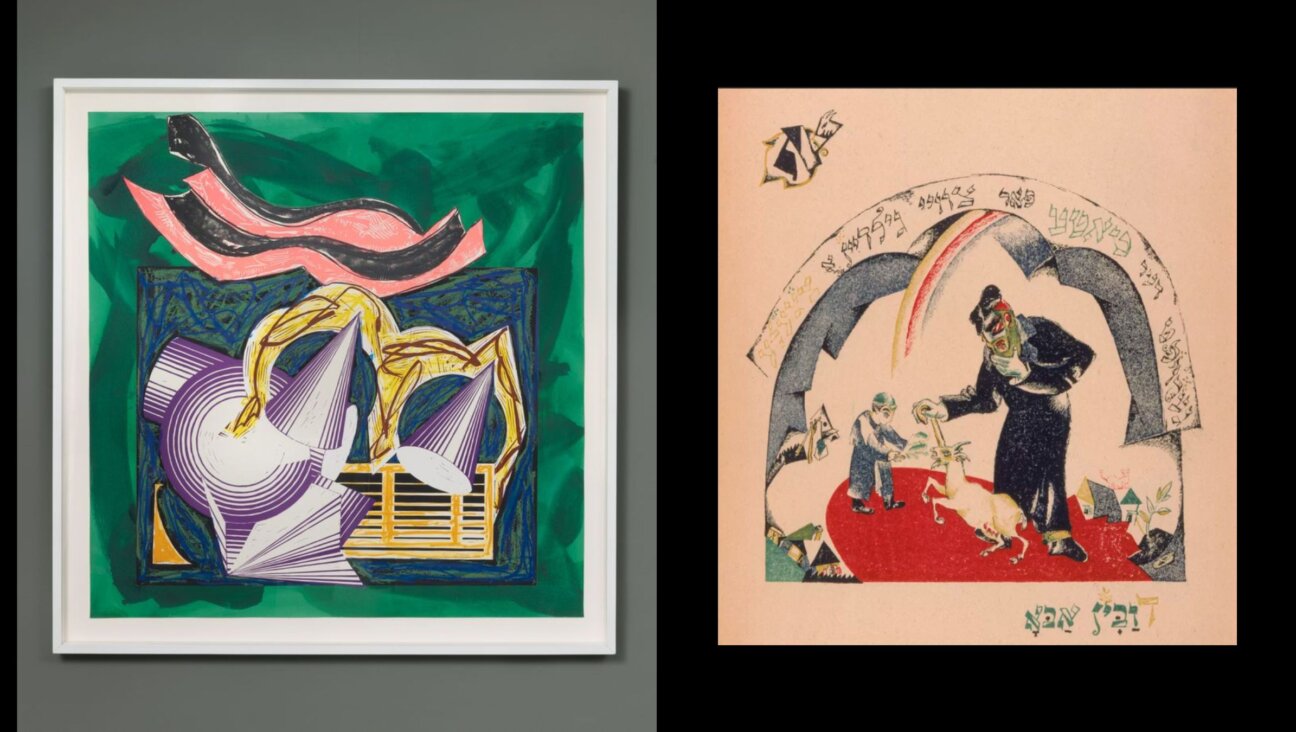

The book begins in an earthly paradise: the mountain resort town of Zakopane, in southern Poland, where Jacob Rosen, a barber, plies his trade. Eidel Mankowicz, a gifted painter visiting from Warsaw, falls in love with the town and the man, and decides to stay. They marry and have a son, Max, and a daughter, Lydia, whose loveliness Eidel captures on canvas. Life is idyllic — until Nazi persecution expels them from their home. After stays in Warsaw and Krakow, they roam from village to village, “their world collapsing upon itself.”

In the end, like millions of their compatriots, they descend into the hell of Auschwitz. Clinch’s vision of the death camp, seen first on a bright sunny day, seems at once authentic and softened — muted by time, or literary necessity, or deference to the oft-stated impossibility of imagining the actual horrors of the place.

There is a contradiction at the heart of Clinch’s enterprise, as with virtually any Holocaust novel. On the one hand, the writer is bound by a quasi-journalistic imperative to re-create the world that survivors remember: the bitter hunger and cold, the random cruelty, the anguish of losing loved ones, the constant threat of death. But the more precise and gruesome the details, the more likely it is that readers (most of them, anyway) will turn away. Clinch’s Auschwitz — tempered by a few small kindnesses and the force of a family’s love — is a place we’re willing to visit, perhaps even compelled to linger.

Clinch’s real interest, in any case, is not in the mystery of inhuman cruelty, but in the humanity that transcends it: the bonds between family and friends, and the redemptive power of art. The novel’s most likable characters are all artists of a sort, even in Auschwitz: Jacob, supremely skilled with scissors and razor, will become a barber to Nazi officers, and Eidel will get a chance to paint again, in two distinct ways, achieving “the truth of technique on one hand, and the truth of the heart on the other.” Gretel, Eidel’s workmate in the camp kitchen, will record the Rosens’ stories, and many others, on scraps of paper and bury them for posterity.

And Max Rosen will escape — like Job, like Ishmael — to become a famous, crotchety painter, “king of the old-school representationalists,” guarding memories and secrets of his own.

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic and a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30