True History of an Unknown Hero of the French Jewish Resistance

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Shortly after she agreed to speak to me for an interview, Charlotte Sorkine Noshpitz tells me that she has had a dream. Members of her Resistance group are seated on the floor, the way children in a group sometimes arrange themselves. She is standing — behind them, looking down at their heads. She is shocked to see them. Most, she says, are dead by now. She was the youngest of her group, 17, and now she is 88. If the others were alive today, they would be nearly 100.

In Nice, France, during World War II, Charlotte Sorkine conveyed groups of children to the Swiss border to be rescued. Under Maurice Loebenberg of the French Resistance, she created thousands of false papers. She accompanied groups of young people who went to join the Allied armies in Spain.

After the Gestapo arrested 24 members of her group, the Armée Juive, in July 1944, she joined an independent liaison group, the Jewish Fighting Organization, and obtained and transported weapons. She took an active part in the liberation of Paris.

For her service in the French Resistance, she was awarded the Médaille de la Résistance, the Croix du Combattant Volontaire de la Resistance, the Médaille des Services Volontaires Dans la France Libre and the War Commemoration Medal. And yet hardly anyone knows her story.

I have known Charlotte for nearly 50 years. We met in 1964, when she and her husband joined us for a Passover Seder at the home I shared with my then husband, Bruce Sklarew, in Maryland. A psychoanalyst, he worked at the National Institute of Mental Health with her husband, Joseph Noshpitz, an eminent child psychiatrist and child psychoanalyst who conducted our Seders for more than 30 years. He died in 1997, at the age of 74, and my former husband and I edited and published “The Journey of Child Development,” his collection of unpublished papers, in 2012.

Though I had wanted to interview Charlotte for decades, as I feared that her story would never be told, she had demurred. “It is not a story, but a life,” she said. “It came about because of the situation I lived in. If it becomes a story, you could rent it. Like a good movie. But it would not be understandable,” she told me. I recall her saying at one time that it would no longer be hers if she told it.

In 1986, when I was thinking of leaving my current life and heading north to direct the artists community of Yaddo, Charlotte gave me two gifts. The first was a tiny book called “The Essay of Silence,” published in 1905. All its pages were blank. The second gift was a small book by Vercors, a pseudonym of Jean Brulle, written in 1942 and called “Le Silence de la Mer” (“The Silence of the Sea”), published secretly in Nazi-occupied Paris. It tells the story of an elderly man and his niece who refuse to speak to the German officer occupying their house. Both gifts reminded me that Charlotte did not wish to make a story out of her experiences.

The impetus for our conversations came in 2012 when I received the spring issue of Prism Magazine, an interdisciplinary journal for Holocaust educators that is published by Yeshiva University. It fell open to a page with a photograph of a young woman who had been a member of the French-Jewish Resistance during World War II. Marianne Cohn had taken hundreds of children to the Swiss border before the Gestapo captured, tortured and killed her — only three weeks before the liberation of Annemasse.

Though Cohn had the chance to save herself, she determined that to do so would put the children at too great a risk, and she refused. I was struck by the similarities between Cohn’s life and Charlotte’s. Could Cohn have been someone Charlotte knew?

Over the years, Charlotte talked informally with my husband and me about the times during the war. But after I mentioned Cohn, and Charlotte agreed to be interviewed, she and I talked in a more deliberate way. We would sit together at the huge dining room table in her house in Washington, D.C., which was filled with her sculptures, including a bust of her father, figures reminiscent of the work of Alberto Giacometti, small abstract metal pieces mounted in wood and hand-blown glass pieces made by her grandson. Over the course of our conversations, among the many things I learned was that Noshpitz did know about Cohn. In fact, one of Noshpitz’s duties was to assume Cohn’s responsibilities of transporting children to the Swiss border.

Charlotte tells me of another dream, this time of her grandmother, whom she does not recall ever dreaming about.

“Where is your grandmother?” I ask her.

“In my kitchen, here in my house in Washington,” she says.

And now she remembers that when her grandmother died, she repeated the words to herself from the Gluck opera “Orpheus et Eurydice” over and over: “I have lost my Eurydice, nothing equals my unhappiness… I am overwhelmed by my grief. Eurydice!”

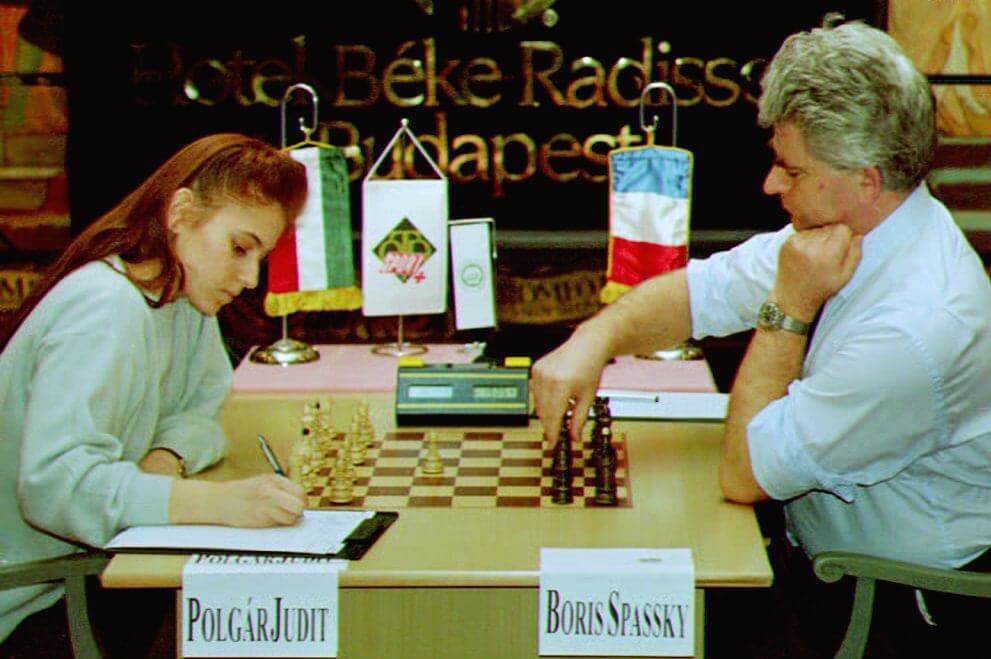

A Life on the Run: As a teenager, Charlotte Sorkine ran weapons and made false identity papers. Image by Courtesy of Charlotte Sorkine Noshpitz

Charlotte Sorkine was born in Paris on February 15, 1925. Her mother was born in Braila, Romania, and her father in Rogachev (now Belarus). They were not French citizens at the time of the German occupation, which is important to note because foreign nationals were taken in the first round-ups. As early as 1940, Vichy laws revoked the citizenship of naturalized Jews and decreed that foreign nationals of Jewish faith could be interned in camps or restricted to residence by regional prefects.

Charlotte’s maternal grandparents lived in the family home, as did her brother, Leo Serge Lazare Sorkine, a poet who served in the Resistance and was betrayed and sent to Silesia to work in the salt mines. He was killed before the Russian liberation too weak to survive a forced march in freezing conditions.

Charlotte grew up in a highly intellectual household. Her maternal grandfather, Wolf Louis Horowitz, born in 1866, was a professor of anthropology who spent much of his professional career at Kings College, London. There were weekly salons with such individuals as Henri Bergson and Gerard de Lacaze-Duthiers. During the war, he and his wife were taken to the Rothschild Internment Center. They both died in 1946. His numerous publications are archived in New York at the Center for Jewish History’s Leo Baeck Institute.

As a young child, Charlotte heard about the Germans and an apparent danger, though not a clearly defined one. She recalls German refugees coming to the door to sell pencils. At one point, she gathered up a collection of prized porcelain dolls marked “Made in Germany,” walked to the balcony of her home and threw them over the railing, where they broke into pieces. Years later, when she and her brother were teenagers, their mother told them that they must attach a Jewish star made of yellow cloth and outlined in black to indicate that they were Jewish. They both wept.

In July 1942, French police came on several occasions in the middle of the night, looking for Charlotte’s father. On July 16, 1942, in the daytime, two French policemen came for her mother. Charlotte packed a suitcase for her. The Nazis declared a raid and a mass arrest where more than 13,000 were taken: 44% were women, 31% children. In Paris in 1988, Charlotte walked us past the prefecture of police: “Here is the place where the policemen served who came to take my mother,” she said. “They were young, embarrassed.”

By this time, Charlotte’s father was in hiding in their house. Her mother was taken to the center of Paris, to the Velodrome D’Hiver, the cycling track, where it was later discovered that Jewish people had been taken in large numbers and kept there for five days without food or water, other than that provided by relief groups, and without toilets or a place to rest. From there they went to internment camps in Drancy, and then by train to Auschwitz, where they were killed.

Legions of Honors: For her service in the Resistance, Charlotte Sorkine was honored with the Médaille de la Résistance (center, black and red stripes). Image by Christopher Parks

Her brother had already left for Nice; their father left shortly thereafter. Charlotte, then 17, remained in the family’s home in Bourg-la Reine with her grandparents. Eventually she headed south to join her father and brother in Nice, in the basement apartment they shared. One day, her father, upon opening a closet in their room, came upon a stash of his daughter’s weapons; by then Charlotte had joined forces with Resistance groups. She realized that she had to arrange to get her father out of the country immediately. “I made false papers for him as a Chinese man, and led him to think that I would accompany him to Switzerland, but as we approached the border I bid him goodbye. A passeur, or one who lead people to safety, guided him to a camp in Switzerland, where he lived out the war. At the Liberation, he returned to Paris. He was shocked to discover that his son had been deported.”

When Charlotte took over Marianne Cohn’s responsibilities, she continued the work of transporting groups of youngsters to the Swiss border. She made false documents; received and transported weapons and money; planted explosives where Germans gathered. One time, she pasted plastic explosives on the wall of a movie theater in Paris where the SS was meeting. “We heard the boom,” she recalled. “It worked! Imagine!”

Among Charlotte’s many responsibilities was guiding men to Toulouse, where passeurs took them to the Spanish border. “Here at night they crossed the Pyrenees to the Spanish frontier and were brought to bordellos as safe houses,” she said. “Some spoke only Yiddish. Some went to join the Resistance in North Africa.”

She recalled riding her bike, with its basket loaded with weapons and weapon parts, when German soldiers confronted her. At that split second — with no time to think — she let her bicycle fall at the feet of the soldiers. They assisted her in getting to her feet, and she rode off.

Often, situations arose that required an instinctive response. One day, she boarded a train for Nice, carrying a suitcase with weapons. Her journey required a train change in Marseille. She chose to sit among the German soldiers because it was far more common for the French soldiers to inspect French passenger bags. The Germans talked with her and helped her off the train in Marseille. They checked her suitcase with their own luggage in the train station, as there was a wait for the connecting train to Nice. “If you want to see a real French football match while we wait for the train, I will take you,” Charlotte told the soldiers.

With that they all went off to the game. When they returned to the station, the German soldiers removed her suitcase — green with a double floor for hiding weapons and money — from the baggage check. They handed it to her and boarded the train for Nice.

Charlotte tells me she has had a dream about her mother: “I saw her from the back, with her navy blue coat and hat. She didn’t even say goodbye.” She tells me this in French. “It cannot be said in English,” she explains. She repeats this phrase in French several times. “I see myself bringing the suitcase. She didn’t even say goodbye.”

Among those in Jewish Resistance organizations in France during the war, some 40% were women — an astonishing figure, considering that women had few rights at this time, including the right to vote, which was not granted until 1944. A very small percentage of girls had matriculation degrees or any university education. Yet women played a major role in the Resistance in both decision-making positions and the carrying out of missions. Charlotte told me she believes that women have quite different instincts than men. “Perhaps not the same species!” she said.

What makes one person seek the hidden contours of safety and another put aside all risk? Perhaps it would have gone differently for Charlotte Sorkine or Charlotte de Nice or Anne Delpeuch, or any of her various identities, had she not opened the door of a synagogue where a Jewish resistance group was forming. And it might have gone differently had she not passed a test she had not known she was taking, given by Lariche, one of the Resistance leaders, at the start of the occupation. She had gone in search of false identity papers and made her first contact with him: “We met in a park. I am with a big, tall man, Lariche, on a bench. All of a sudden a man comes and tells him that such and such were arrested and tortured. I didn’t move. I waited and waited. Then Lariche talked with me and gave me the papers. I suppose when that man came to talk in front of me, it was to see my reaction.”

When I asked about the change in her own thinking, from child to Resistance fighter, she responded: “Risks and fear are two different things…. When you are young, you don’t think things can happen to you. But you don’t think of it; you have something you must do.”

“But,” I said to her, “some were hidden. OSE [Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants, a humanitarian organization for the rescue of children] took care of and hid the children. Why didn’t you take that route? You could have gone into hiding.”

“I had no choice,” she told me. “You cannot go back. My grandparents were arrested; my mother taken; my brother sent to the free zone. It was my destiny.”

After the war, Jean Paul Sartre met with some of the young people who had served in the Resistance, in coffee houses, cellars and cafes. His thinking about existentialism seemed to be in accord with their lives at that time: Where do they go from this moment? They cannot reconstruct their former lives; parents, siblings and family structures are missing. What do they do with what they, as youngsters, have been required to learn in these war years: risk-taking, destruction, loss of life, loss of trust and, on the other hand, deep trust in their particular group?

At first, Charlotte began to study — at an atelier for life drawing classes, then on to the Sorbonne to study psychology, to the Louvre for the study of art history and to language school. She had a darkroom in her house, and at the time, Richard Wright was in Paris and arranged with her to work there. “Black Boy,” the first half of his memoir, had recently been published. It took another 32 years for the second half to be published posthumously.

Charlotte was offered the opportunity to come to the United States to study mental health treatment centers and new therapeutic disciplines, including art, dance and drama therapy, and to aid a group of French doctors who planned to build a treatment center outside Paris, modeled on the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kan. She boarded the shop the Ile de France and headed toward New York. The lengthy and rough trip caused many to become ill; however, she and a few others weathered it well. Among her companions were Ernest Hemingway and the folk singer Josh White.

“You want a screwdriver?” Hemingway asked her. She had no idea what it was!

“A Bloody Mary?” A strange name to this young Resistance fighter!

“We had a wonderful few days together,” she said.

Joseph Noshpitz and Charlotte Sorkine met at the Menninger Clinic. They eventually married in Paris. When it came time for him to say, “I do,” a chorus of her Resistance compatriots, concerned that his French was not sufficient, chimed in, “Oui, Monsieur le Maire!”

“I married them all!” Charlotte Sorkine Noshpitz told me.

Now in her 88th year, Charlotte Sorkine Noshpitz carries with her the knowledge of how one makes the decision to take action when human beings step across the line in their treatment of one another, and she reminds us of our own obligation to stop injustice when we are aware of it.

“What kind of a tree do you want to be when you die?” Charlotte asks me. “A rosebush? There is no conclusion. It is a circle. It will start again. Always there will be people who do these things. No end. As in Vietnam, young people were taught to be aggressive. The military teaches the young. Look at today. We are still doing it today. We must transmit to our children, not by example, not directly, but to mold character, the role of a grown-up. I will evaporate one day. Floating around like waves and clouds over the houses. All my world. You will see me. Like a Chagall. That’s my conclusion.”

Myra Sklarew is emerita professor of literature at American University. From 1987 to 1991 she served as president of the Yaddo artists community, and in 1977 she won the National Jewish Book Award for poetry. She is the author of the forthcoming “A Survivor Named Trauma: Holocaust and the Construction of Memory“ (SUNY Press).