Heading Into the ‘I’ of the Knaidel

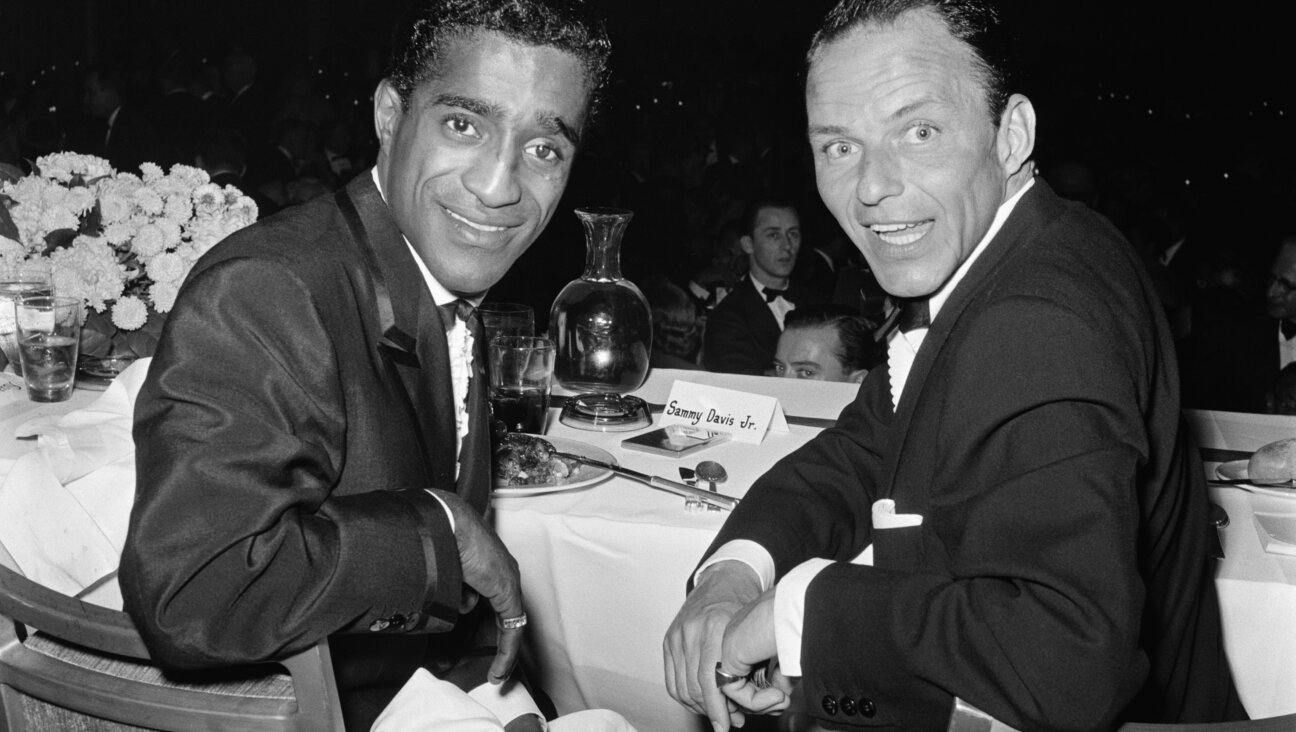

Spelling Trouble: 13-year-old Arvind Mahankali won this year?s Scripps National Spelling Bee and uncorked a linguistic debate. Image by Getty Images

The point that has been missed in the great knaidel (knaydel? kneidel? kneydl?) controversy is that the real problem isn’t the spelling of Yiddish words in Latin characters. It’s the spelling of English words in Latin characters.

In the Hebrew characters that are native to it, Yiddish has been, for the most part, ever since undergoing a series of modern spelling reforms, a consistently spelled language. (The one exception to this is its large number of Hebrew-derived words, which have retained their distinct Hebrew orthography despite 20th-century campaigns, particularly in the Soviet Union, to spell them like other Yiddish words.)

This means that when educated Yiddish speakers read a Yiddish word on a page, they know how to pronounce it even if it is unfamiliar to them, and that when they hear one spoken, they know how it should be written. Although their way of pronouncing what they read may vary according to the regional variety of Yiddish that they speak, it will remain invariable for any given speaker.

This is true, in one degree or another, of most European languages, which have had spelling irregularities caused by hundreds of years of speech developments ironed out in modern times. It is not true of English, in which no significant revision of spelling has taken place since the 18th century. The result has been that modern English spelling is wildly inconsistent.

A native English speaker encountering a new word in print may have no idea how to say that word aloud. (If, for instance, the word — I have just opened my dictionary at random — happens to be “susurrant,” do I say “SOO-seh-rint,” “SUH-seh-rint”or “suh-SUH-rint”?) If an English speaker hears something that sounds like “sick-a-tricks,” how does he write it? (The answer is “cicatrix.”) The same small sound can be spelled in English as “you,” “yew,” “hue,” “u” (as in “usurer”), “yoo” (as in “yoo-hoo”), “eu” (as in “euphemism”), “hu” (as in “humor”), “yu” (as in “Yukon”), and “Hugh.”

Written English has letters representing consonants that are pronounced differently without rhyme or reason (why do we say “get” with a hard “g” but “gem” with a soft one?); letters for vowels that can be pronounced in six different ways (think of the “a” in “father,” “fat,” “many,” “another,” “ball” and “gate”), and letters that aren’t pronounced at all (“h” in “hour,” “p” in psychology, “gh” in high, “t” in “whistle,” “n” in “damn,” “b” in “lamb,” to name a few). It’s a nightmare for spellers, whether they’re in night school in China or first grade in Kentucky. It’s no wonder that you can win $30,000 for spelling “knaidel.” You might also have spelled it, apart from the more common alternatives, “knadle,” “kneighdel” or “cunadile.”

It’s thus pointless to argue about the word’s correct English spelling. Sticklers for protocol, and serious Yiddishists, may prefer “kneydl,” which follows the transliteration rules of YIVO, New York’s Institute for Jewish Research, the closest thing there is to a Yiddish academy of language.

But although the YIVO rules are consistent, they don’t guarantee success, either. What’s to keep our English speaker from seeing “kneydl” and saying “needle,” with the “k” silent as in “knight” and the “ey” as in “key”?

Moreover, the YIVO rules for transliteration into English can be confusing in their own right. In the first place, unlike Yiddish in Hebrew characters, a transliterated Yiddish unavoidably promotes a specific regional pronunciation — in the case of YIVO, that of the northeastern Yiddish of Lithuania, where the organization was founded, in Vilna, in 1925. Speakers of Polish or Ukrainian Yiddish, for example, whose word for “good” is git (pronounced “geet”), will find the YIVO spelling of gut (pronounced “goot”) off-putting.

Secondly, there are YIVO transcriptions, particularly of certain vowels, that are misleading for an English speaker unless he already knows what they stand for. The long “i” of English “eye,” for instance, is transcribed “ay,” even though in English this is almost always the vowel of “say,” so that the Yiddish word for “wine,” which, like its English cognate, rhymes with “fine,” has the YIVO form of vayn; the final Yiddish ayin, which stands for “eh,” is spelled with just an “e,” which may lead to a YIVO transliteration like mame, Yiddish for “mother,” being pronounced as “maim” instead of “MAH-meh.” YIVO’s vowel-less, post-consonantal “l” in a word like kneydl suggests a tongue-twister when it actually has the same sound as English “l” in “cradle” and “civil.”

In the final analysis, no system of transliterating Yiddish in Latin characters can be both consistent and natural in English, because the vagaries of English spelling rule this out. That being the case, one may as well let popular usage determine the matter with Yiddish words that have entered the English language. I don’t know why the organizers of the Scripps National Spelling Bee chose to stake $30,000 on “knaidel” when competing spellings exist, too, but if that’s what a kneydl is worth when spelled that way, who would want to spell it differently?

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO