Allan Sherman Was Once Bigger Than the Beatles

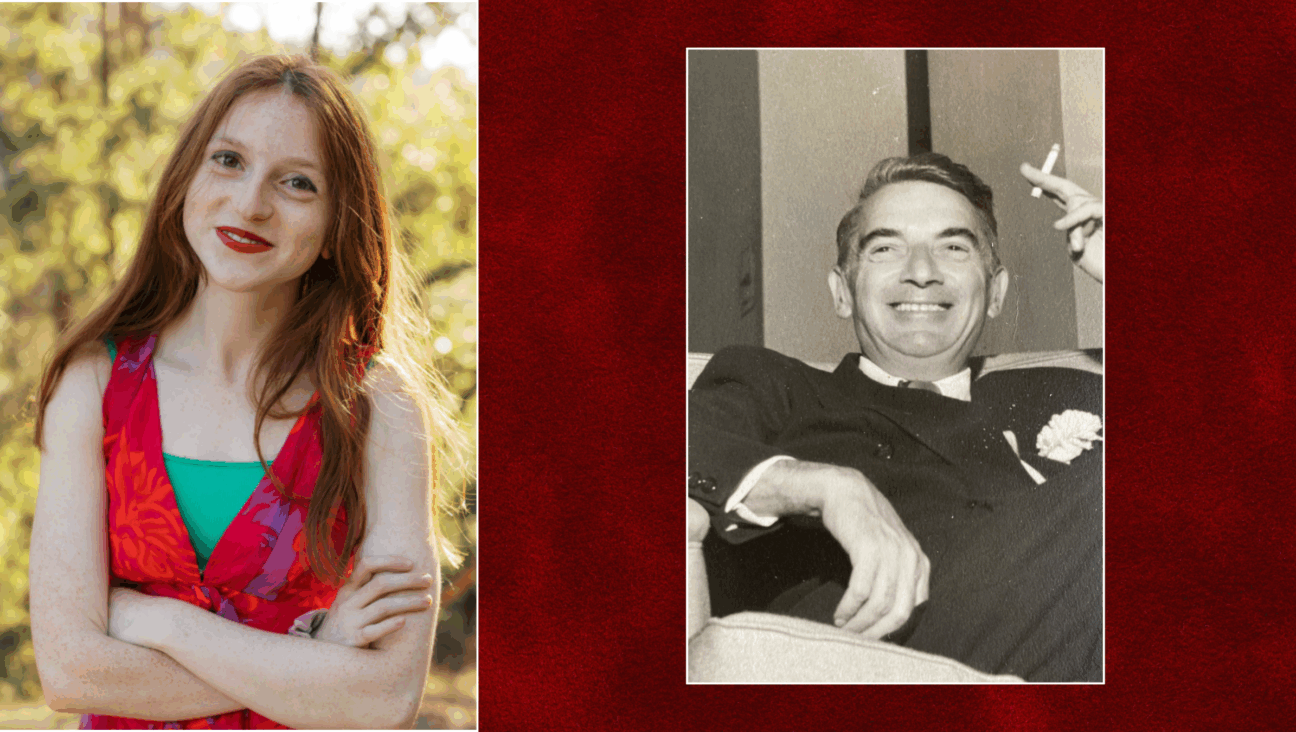

My Son, the Folk Singer: Approximately fifty years ago, Allan Sherman had three consecutive No. 1 comedy albums, selling more than Frank Sinatra or Elvis Presley ever sold out in such a short span of time. Image by Courtesy of Mark Cohen

● Overweight Sensation: The Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman

By Mark Cohen

Brandeis University Press, 320 pages, $29.95

I loved visiting my maternal grandparents in the Elmhurst section of Queens. Although they lived in a modest, two-bedroom apartment on a side street tucked between Broadway and Roosevelt avenues, the place seemed exotic, as I was coming from suburban Long Island.

I loved sitting in the living-room window overlooking 77th Street; there I could see all the way down to the corner of Broadway, where the action was, all the way to where my grandfather used to run the soda fountain store. My grandmother would typically and lovingly insist I “come down from the window” and sit in a chair, a perch from where I would be safer, as in her mind the whole world conspired to do harm to her beloved children and grandchildren (understandable, as the world had seen fit to destroy virtually her entire extended family, almost all of whom had remained in Europe, during “the war”).

But what I really loved about visiting my grandparents was that it meant I got to listen to their copy of Allan Sherman’s LP, “My Son, the Folk Singer.” And listen to it I did, every time I visited, so much so that to this day, nearly 50 years later, I still remember most of the lyrics to Sherman’s Jewish-inflected parodies of classic folk songs: parodies that served both to satirize the folk revival itself and to poke gentle fun at postwar American Jewish life — the very life my family was living.

Sherman’s songs on that record album — “The Ballad of Harry Lewis,” “Sir Greenbaum’s Madrigal,” “Shake Hands With Your Uncle Max” — captured an entire culture, an entire way of life.

His songs were populated with iconic ethnic markers: the post-Yiddish English dialect my grandparents and even many first- and second-generation American Jews spoke in expressions like “How’s by you?” — a homophonic translation of the Yiddish greeting “Vos makhstu?”; the seltzer they drank; the matzo balls and chicken soup they ate; their professions as tailors, doctors, lawyers and accountants, and their favorite recreational pursuits: “The Catskill ladies sing this song / Hoo-hah, Hoo-hah / Sitting on the front porch playing mahjong / All hoo-hah day,” Sherman sang, to the tune of “Camptown Races.”

I was too young to understand at the time, but Sherman was radically tweaking postwar American Jewish life while paving the way for a whole slew of Jewish-flavored American comedy — from Mel Brooks to Woody Allen to Robert Klein and David Brenner, all the way through to Jerry Seinfeld and the Larry David of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” as Mark Cohen convincingly argues in his exhaustive and gripping new biography, “Overweight Sensation: The Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman.”

I was also too young to appreciate that for one brief year or so, Sherman was a huge star. In 1963 he was a pop sensation with three No. 1 consecutive comedy albums selling millions apiece — more than even Frank Sinatra or Elvis Presley ever sold in such a short span of time. He was a guest on all the major TV talk and entertainment shows; he sold out concerts around the country, and he even counted among his fans President John F. Kennedy, who was known to break out into a verse of “Sarah Jackman,” Sherman’s parody of “Frere Jacques.”

And then, like everyone else who was popular before 1964, Sherman got swept aside by the Beatles, who utterly changed the notion of what was cool and hip. Instantly Sherman became something of a square, and weakly aimed his satirical muscles against the youth culture of the 1960s — even the Beatles themselves in “Pop Hates the Beatles.”

To many today, Sherman may seem like a novelty act, a one-hit wonder (for his Grammy Award-winning single, “Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh!”) or a pop-culture footnote. But as Cohen makes clear, it’s too easy to overlook the subversive nature of his work: He was a kind of precursor to the radical Jewish culture of Heeb magazine or the music of John Zorn. Parody was Sherman’s form.

He took the products of mainstream American culture — folk songs, Broadway show tunes, pop music — and mined or reimagined them for their latent or possible Jewish content. In this manner, he was doing something very traditional, and very Jewish, engaging in a kind of pop-culture version of midrash, filling the gaps in the story (particularly the Jewish gaps) that were only hinted at in their original versions.

Cohen quotes Sherman asking the rhetorical question, “What would have happened, how would it have been, if all of the great Broadway hits of the great Broadway shows had been written by Jewish people?” Of course they were, and he knew it. Just asking the question itself was his most provocative, radical act.

Seth Rogovoy is the author of “Bob Dylan: Prophet, Mystic, Poet” (Scribner, 2009) and is a frequent contributor to the Forward’s arts and culture section.