When We Marched Together in Selma

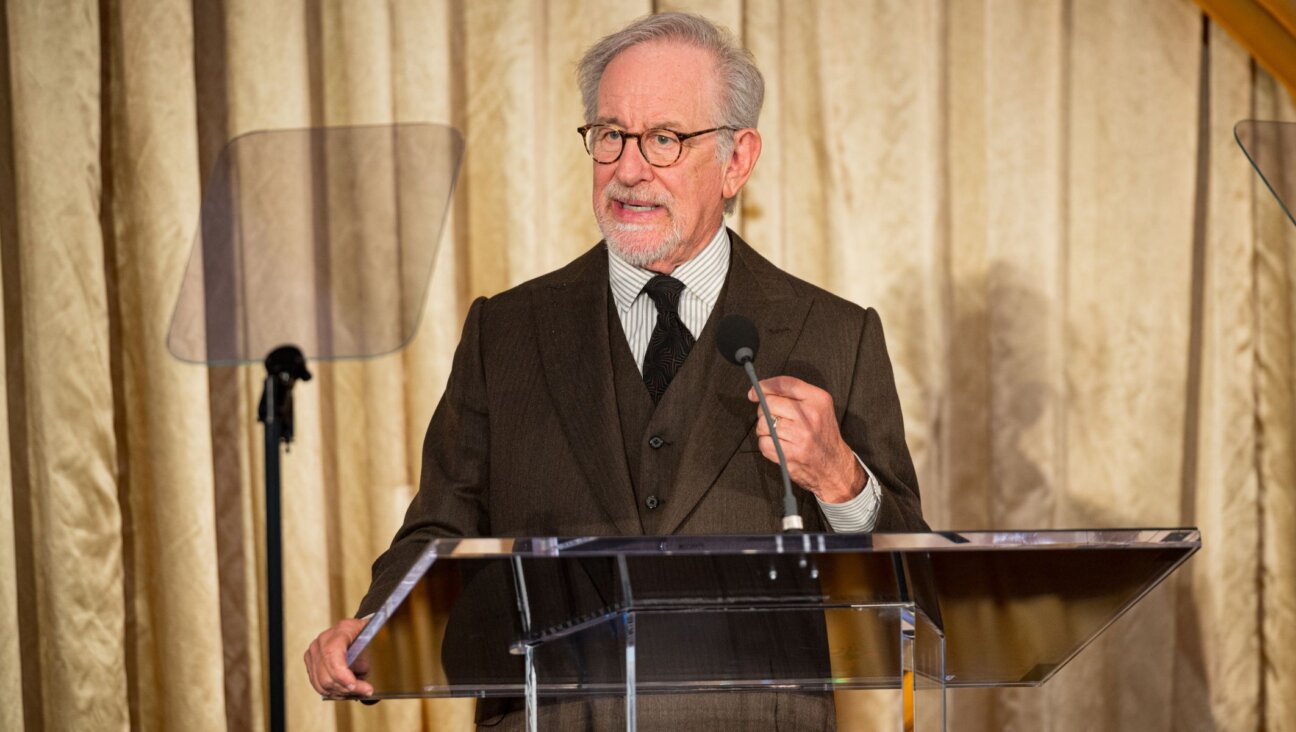

One Small Step: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. marched with Rabbi Abraham Heschel (far right) in 1965. Image by Getty Images

Selma. Nearly 50 years ago it was violent Selma, impossibly racist Selma, site of Bloody Sunday, when peaceful civil rights marchers made their first attempt to cross the Pettus Bridge on the way to the state capitol in Montgomery, Alabama. They succeeded on their third attempt, protected by federal troops. You’ve seen the famous picture — Martin Luther King, Jr., heading the Selma marchers, with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Greek Orthodox Archbishop Iakovos. Incongruously, they’re wearing leis, a gift from a Hawaiian delegation.

Since Bloody Sunday and the protests leading up to it, the town has been associated internationally with racism, helped by its burly segregationist Sheriff Jim Clark from central casting, who led state and local officers with tear gas and truncheons; soon, it’s going to become known by another generation — the feature film “Selma” shows King’s struggle there to secure voting rights for African-Americans. The filming in Atlanta, Selma and Montgomery, has just wrapped up; producers include Oprah Winfrey (who has a small role) and Brad Pitt’s film production company Plan B. It will be distributed by Paramount and Pathé, with a limited release on Christmas Day.

Next spring, expect international media coverage on the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, when activists and politicians, civil rights veterans and college students on break will flock to the city for the Jubilee during March 5-10 in 2015.

The annual commemorative weekend event has drawn Barack Obama, the Clintons, Joe Biden, Jesse Jackson and others. This year, rising leader Rev. Dr. William Barber of North Carolina was a featured speaker.

Back in 1965, after the first failed attempts to cross the bridge, King called on clergy from throughout the United States to join him. The American Jewish Committee sent him a telegram praising his “remarkable leadership and inspiration” and condemning police brutality.

Heschel, who taught Jewish mysticism at the Jewish Theological Seminary, was very close with King, said Susannah Heschel, the Eli Black professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College. She notes that her father’s writing on racism was “full of passion,” even before he had much contact with African Americans. He was born in Warsaw, pursued secular and religious studies and teaching in Germany in the 1930s, and was deported by the Nazi regime to Poland. He was able to leave for England in 1939, and arrived in the U.S. in 1940.

The morning of the successful march on March 21, 1965, King, Heschel and the archbishop all prayed in their own spaces in the front room of the spacious A-frame home of Jean Richie Sherrod and Dr. Sullivan Jackson, which had become the headquarters of the Selma Movement. Their daughter Jawana, then a 4-year-old, remembers seeing Heschel at the door and thinking that Santa Claus had arrived. Now, many years later, Jawana has created a foundation in honor of her late parents, and plans to convert the family home into a house museum, ready for viewing by March.

At the annual Jubilee weekend in early March this year, a few miles from the spot where the Battle of Selma is reenacted every April, thousands of marchers from throughout the U.S. peacefully and often joyfully walked across the bridge, the highlight of a weekend of speeches, films, dance, music, theater, prayer meetings, a street fair, political workshops, and even a Miss Jubilee contest — all to mark the 49th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. Most, but hardly all, of the marchers were African-American.

A century ago, Yiddish journalists and poets wrote about lynchings. In the 1930s through the 1960s, Jewish groups formed a coalition with labor groups, mainstream Christian groups and the NAACP, said Rabbi David Saperstein, director of the Religious Action Center for Reform Judaism in Washington, D.C. Two towering African-American leaders, Ralph Bunche and W.E.B. Du Bois, advocated for the establishment of Israel; Bunche, though less enthusiastic, lobbied Haiti and Liberia U.N. delegates to vote for statehood.

This was before Jewish groups filed legal briefs against affirmative action cases; before the cry of “Zionism is Racism” became the black nationalist and Third World j’accuse; before Jesse Jackson dubbed New York City Hymietown; before the Nation of Islam made accusations ranging from the absurd (Jewish doctors infecting African children with the AIDS virus) to the grossly exaggerated (Jews were the main slave traders); before a car accident in Crown Heights led to a riot.

The two men shared a deep friendship as well as theological affinities, according to Susannah Heschel. King used the Exodus motif instead of invoking Jesus, she said. “Both men assumed a God of pathos, involved with the affairs of humans. Both spoke the language of Biblical prophecy.”

Some bitterness creeps into her voice: “For many years, and after my father died [in 1972], Jewish people didn’t talk about it — they were not proud of him or Jews involved in civil rights.”

The men’s friendship evokes nostalgia for a golden age of black-Jewish relations. But even half a century ago, there was tension between blacks and Jews, mostly resulting from economic conditions, said Cheryl L. Greenberg, author of “Troubling the Waters: Black-Jewish Relations in the American Century.” It’s true, however, that Jews were overrepresented in civil rights work, and a majority of Jews supported civil rights, she said.

A new coalition is bringing together blacks and Jews, as well as others, for progressive change. That Jubilee Saturday in Selma, Rev. Barber spoke about a progressive coalition that fights for voting rights, the extension of unemployment insurance, more funding for public education and health care, and more equitable taxation. A big man with a long face, dark curly hair and a short graying beard, a red stole draped over his dark suit and white collar, he stood up awkwardly, using a cane. “Young, old, black, white, gay, straight all have a part in the movement,” he said. Jews, Protestants, Catholics and Muslims should be able to work together, he told a group in the courthouse. He was not pandering to the crowd, which was at least 90% African-American. Barber, head of the North Carolina NAACP and longtime minister at Greenleaf Christian Church, Disciples of Christ, in Goldsboro, North Carolina, preached several times during the Jubilee weekend, displaying rhetorical thunder. Just after the bridge-crossing, he went through a litany of heroes who had “marched on” their antagonists from the biblical to the historical: Moses, David, Daniel, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abadnego, Jesus, Rosa Parks, King, and Thurgood Marshall. “When we march, God shows up,” he said. Some in the standing crowd marched in place, and a little boy sitting on a chair moved his feet up and down.

Barber has spearheaded the Moral Monday movement, a weekly protest at the North Carolina capitol in Raleigh that addresses public issues such as poverty and injustice. The largest group of multicultural protesters in Raleigh numbered 80,000, which included rabbis (most flavors but Orthodox), organizations such as Carolina Jews for Justice, along with myriad other groups and individuals.

Barber spoke in Madison, Wisconsin, twice this year. “Reverend Barber has an amazing capacity to connect currents of what we’re living today with prophetic thinking,” said Madison-based labor lawyer, author and activist Jon Rosenblum, who helped bring Barber north. In July, the minister was in the national media spotlight several times, with coverage of his public prayer before a Republican small-town North Carolina mayor set off on a march to Washington to protest a hospital closure.

Rabbi Fred Guttman of Reform Temple Emanuel in Greensboro, North Carolina, came to Selma for the Jubilee and wore his tallit during the reenactment of the bridge-crossing. Of Barber, he said, “No one else has been nearly as successful in creating an inclusive community since King. His intellect and speaking style, he reminds me of Martin Luther King… When Dr. Barber speaks, I sometimes feel I’m listening to a biblical prophet.”

“What brought everyone together was his openness,” said Lucy Dinner, senior rabbi of Temple Beth Or in Raleighs. “If one was discriminated against, all were discriminated against.” And so it seemed natural that before a Saturday morning rally at the state capitol, she arranged to hold services at the chapel of Shaw University, a historically black university in Raleigh.

Do these mostly Southern activities portend or demonstrate the establishment of a relationship between blacks and Jews? Yes, says Greenberg. She’s seen the rise of black-Jewish alliances to tackle global issues such as the environment and social justice. Jawana Jackson, who was born and raised in Selma and who lives in Atlanta, has been a member of the city’s black-Jewish coalition, founded more than 30 years ago by U.S. Rep John Lewis and Sherry Franks of the Atlanta American Jewish Committee. The American Jewish Congress established the Black-Jewish Economic Roundtable meeting in Boston almost 20 years ago; Operation Understanding, a leadership program for black and Jewish youth, began in Philadelphia in 1985. Groups of black and Jewish students in about a dozen cities, from Philadelphia to Dallas, have traveled together — to the Southern U.S., Africa and Israel, said Saperstein. Moral Mondays, he said, are one example of the kinds of coalitions forming now. Jews are working with a range of ethnic groups on social justice issues.

“I feel the black-Jewish partnership has become diluted — for good reasons,” he said. “There’s probably more going on than in the ’60s. Look around America: You do find blacks and Jews working together all the time — it just doesn’t get attention.”

Jews were disproportionate in their support of Barack Obama, and their support mirrored that of African Americans, notes Ann V. Schaffer, director of the AJC’S Arthur & Rochelle Belfer Center for American Pluralism. “[I]n the past two presidential races,” she wrote in an email message, “Jews (74% and 70%) were second only to African Americans (95% and 93%) in voting for Barack Obama.”

Though Selma remains the only designated iconic place in the state of Alabama, according to a recent political atlas it is a small town (with a population under 20,000 and falling). The latest preliminary unemployment rate is 14%, and 86% of students in the county receive free or reduced lunch. Nearly a million Alabamans, out of a population of less than five million, are dependent on food stamps. Selma’s downtown has a spacious library, ante and postbellum brick buildings, and a family jewelry store in a restored art deco Kress department store, in addition to boarded-up storefronts, some pf them previously owned by Jewish merchants, a revived movie house that has died, and a city-owned hotel that has experienced management woes. A transplanted Atlantan has heroically restored the Harmony Club, a three-story brick building that was a Jewish men’s social club. Now you can count the Jews in Selma on two hands

Jawana Jackson hopes to have her house museum up and running by the end of the year. There visitors will see the phone where King received calls from President Lyndon Johnson, and the bed that collapsed under the combined weight of several prominent activists in pajamas. It will also host multicultural, interfaith events. Jackson said she has always felt a kinship with Jews. “There are no other people that I have related to so closely in my life.”

S.L. Wisenberg is the author of “Holocaust Girls: History, Memory, and Other Obsessions.” She is currently working on a book about the South.