How Man Ray Drew on Math, Shakespeare — and Shoah

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

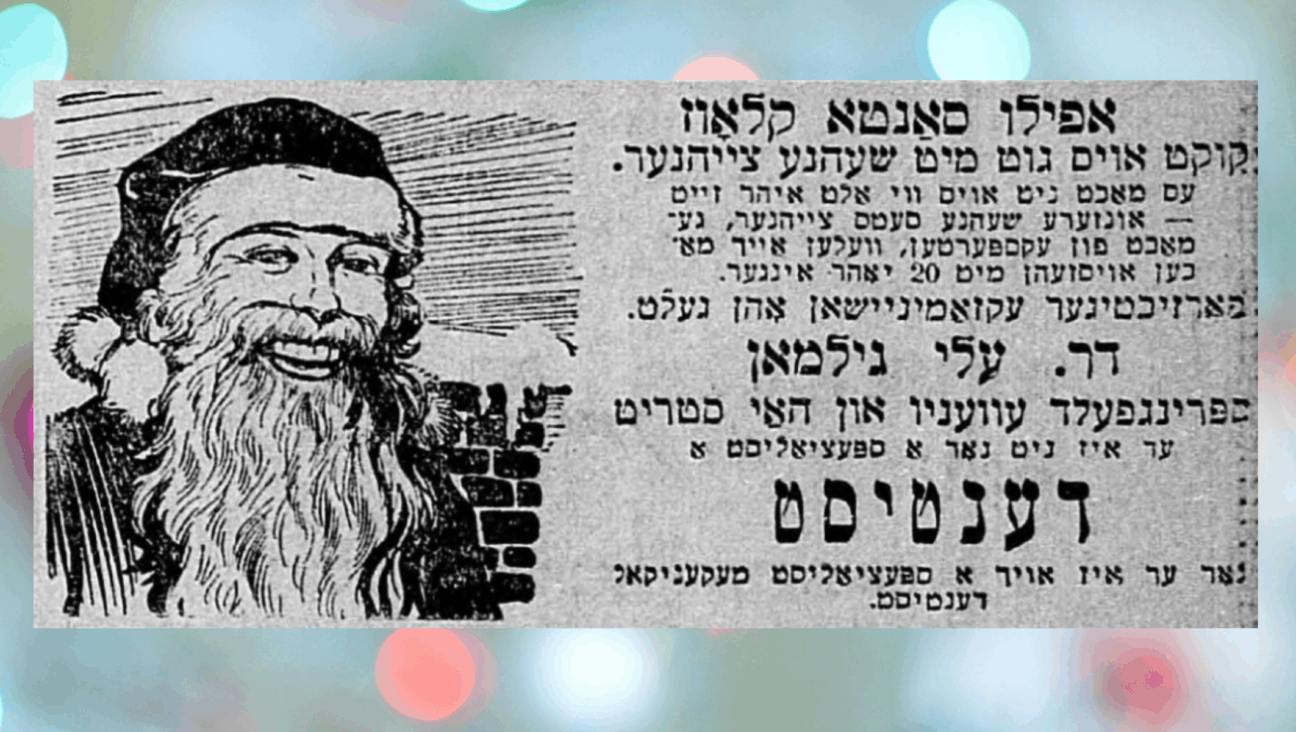

From 1934 to 1935, at Paris’s Institut Henri Poincaré, surrealist artist Man Ray photographed dusty mathematical models, which he said he found baffling. But the Philadelphia native, born Emmanuel Radnitzky, had to abandon the photos when he fled the Nazis for Hollywood. In 1946, he returned to Paris and retrieved the photos; two years later, he painted a series of 23 works, each of which drew its title from a Shakespeare play. The two components of the series “Shakespearean Equations,” then, serve as bookends to the Holocaust.

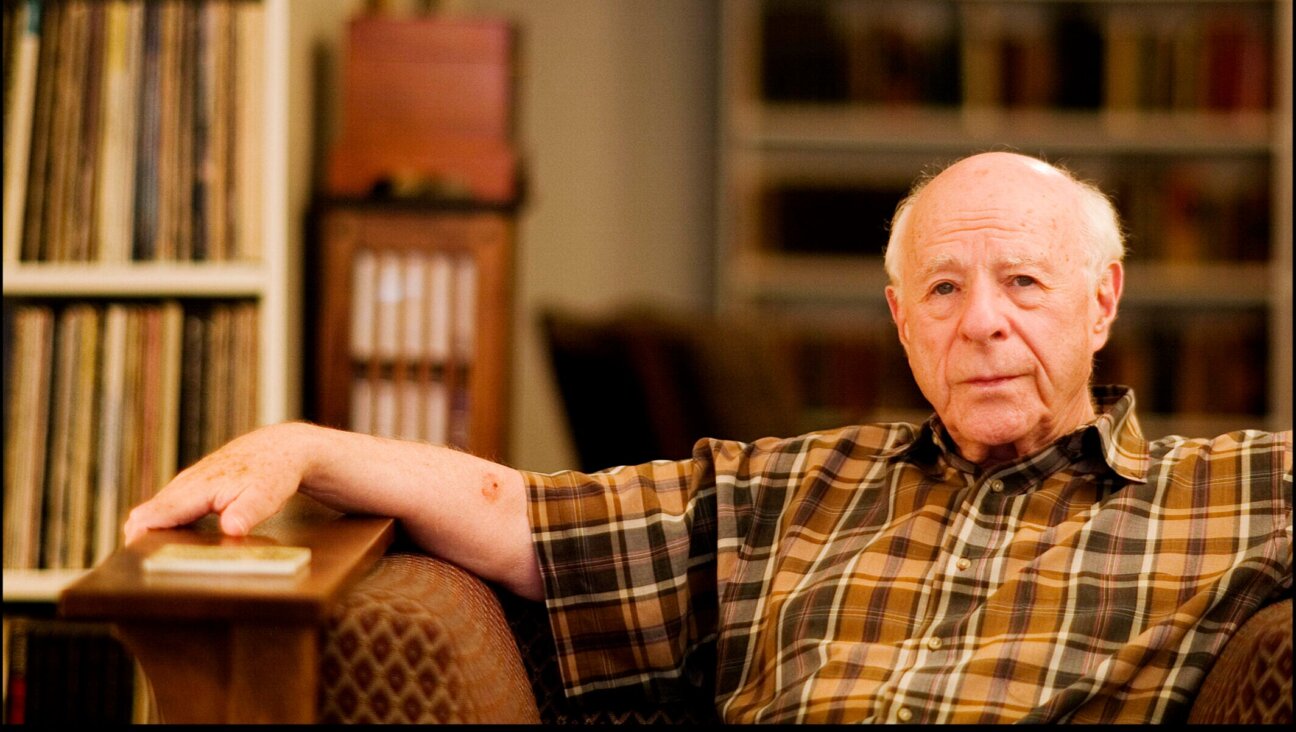

The mathematical context of Man Ray’s work had not received scholarly attention until the new exhibit “Man Ray — Human Equations: A Journey from Mathematics to Shakespeare” (through May 10) at Washington D.C.’s Phillips Collection, according to exhibit curator Wendy Grossman, a photo historian who calls herself a “late convert” to the paintings.

“Man Ray’s paintings in general haven’t gotten nearly the amount of critical attention, scholarly attention, and interest as his photographs,” says Grossman, a curatorial associate at Phillips. “He’s famous for being a pioneering photographer of the 20th century, and his paintings have kind of gotten lost in the shadow of that fame.”

Whole World In His Hand: Man Ray’s ‘Assemblage.’ Image by © Man Ray Trust Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem by Avshalom Avital

The artist, who began photographing his own paintings in 1916 because he was frustrated with others’ attempts to capture them for promotional materials, claimed to have been interested solely in the mathematical models for their forms, rather than for the equations they represented. But there are plenty of reasons to approach quotes from surrealist artists with a dose of skepticism.

“People take Man Ray at face value at risk. There’s always more going on when Man Ray says something than one could initially perceive,” Grossman says, noting that Man Ray wasn’t disinterested in math. “He didn’t understand the math of those models, which by the way, most people don’t,” she says. “He was intrigued by the idea that mathematicians could take abstract ideas and turn them into visual form.”

In his exploration of those abstract forms — which included chess pieces in a manner that disrupts and complicates the simple beauty of the game — Man Ray drew to some extent on current events. To be clear, the Holocaust was not the primary or even a major focus of the series, but thumbing through the exhibit’s comprehensive catalog — itself a beautiful object, designed by Eileen Boxer — one finds several works where the horrors of World War II surface.

A free-standing door divides 1939’s “Fair Weather” into two zones, and despite the bright colors of two geometric figures on either side of the door — whose keyhole oozes blood ominously — the shadowy palette of the background, and two trees that might as well be pitchforks alongside a blasted stone wall, suggest a very dark subject matter. Alongside the trees and wall, a mathematical book lies on the ground near one of the mannequin’s feet. Man Ray’s subject matter, according to the Philadelphia Museum of Art website, also includes nightmares he had of “mythical beasts fighting on his roof, and of an affair between his maid and carpenter.”

“He was very aware of the threat of war on the horizon,” Grossman says. “It is among several canvases that have been frequently interpreted as his sense of impending doom about what was going on on the continent.”

In “The Red Knight” from 1938, a tan pawn is somewhat obscured by the white knight chess piece (i.e. a horse’s head) in the foreground. In the rear, a red figure, which is only slightly meatier than a skeleton, approaches. “The monumentalized horse’s head in the foreground plays a twofold role,” Grossman writes in the catalog. “It signifies both a game piece and the personification of armored cavalry crossing over precarious, checkered territory, symbolically intertwining chess and war in an unsettling theatrical tableau.”

Adina Kamien-Kazhdan, curator of modern art at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, which co-organized the exhibit with the Phillips, says that Man Ray’s previously understudied series approach mathematical models with “wit and sensitivity.” (The Israel Museum’s Man Ray collection numbers 103 works.)

“Man Ray was inspired by the mathematical models but proceeded to turn these stable educational forms on their heads,” she says. “By associating the shapes he saw in these mathematical models with human anatomy, the artist reconceptualized these learning aids in unexpected ways, thereby subverting historic academic resources.”

The evolution of one work in particular underscores the almost absurdist ways that Man Ray played with mathematical models and with chess pieces. “Disillusion” (1940) began as a canvas arranged vertically, with a hand holding up a sphere decorated to evoke a globe. A subsequent painting, “As You Like It” (c. 1948), follows the prior work, but at some point Man Ray crossed out the hand in thin strokes and wrote, “remove hand.” In “As You Like It” (1948), the hand is gone, and just the globe hovers in mid air, inside a trompe l’oeil frame.

Gone, in the final work, are the ominous, discombobulated land masses from the original globe — which one is inclined, as Grossman does in the catalog, to associate with the chaos of war. But “As You Like It,” with its reference to the play famous for the line “All the world’s a stage,” still reflects some of that terror and violence in the extreme shadow engulfing the better part of the globe. “To me, it’s the most enigmatic [work] in the sense that… the planet turns into a metaphysical sphere — spiritual, or a crystal ball maybe,” Grossman says. “There’s so much going on here.”

Menachem Wecker is co-author of the new book “Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education,” published by Cascade in 2014.

‘Man Ray — Human Equations’ is being exhibited at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. thru May 10.