The Secret Jewish History of Joni Mitchell

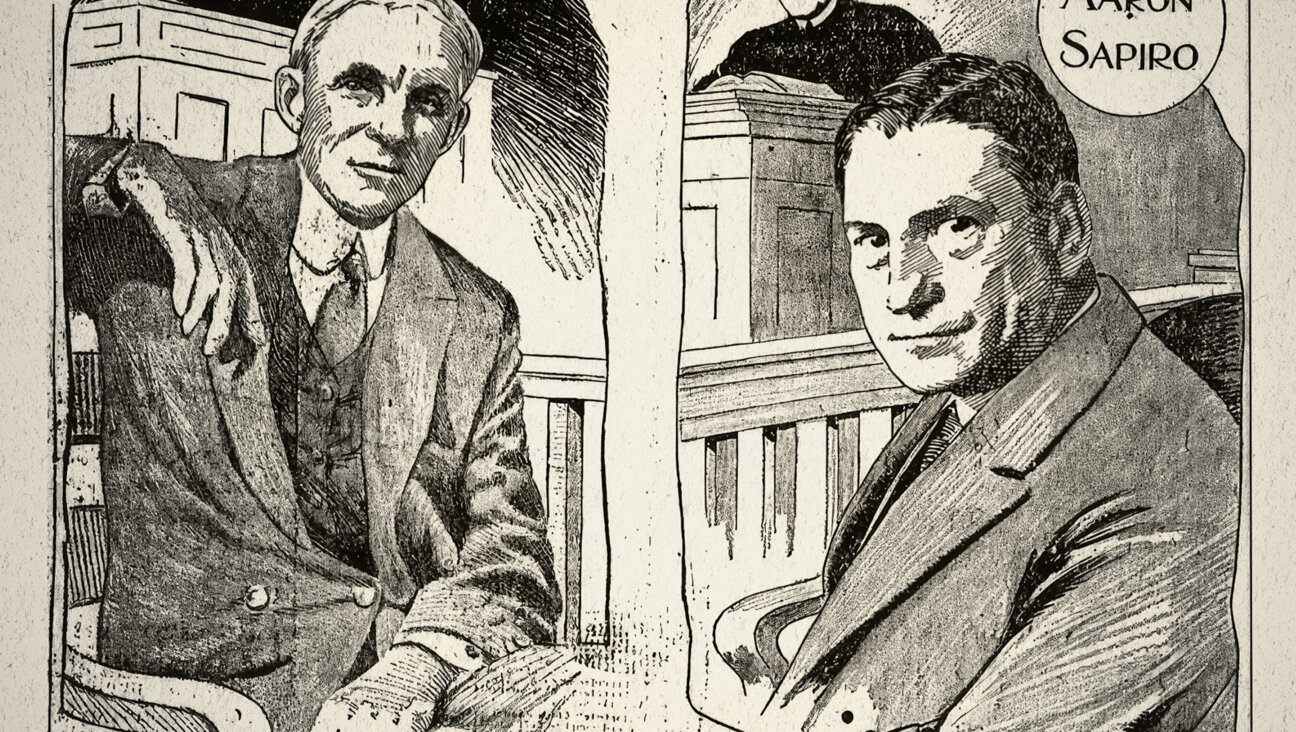

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Last spring, obituary writers were scrambling when reports began surfacing that Joni Mitchell was knockin’ on heaven’s door. Rumors had the folk-rock poet lying on the floor at home for days before someone found her either unconscious, in a medically induced coma and near death, or out of a coma but paralyzed and unable to communicate. But lately, it seems as if these reports have been greatly exaggerated, and Mitchell is apparently making a full recovery.

Mitchell is widely acclaimed, and rightfully so, for being one of the greatest lyricists and musical visionaries of the rock era: the equal of Bob Dylan and — well, there are no other equals. Mitchell and Dylan share the seemingly paradoxical status of being utter mavericks who have had unparalleled influence over everyone who followed them. In Mitchell’s case, that pretty much includes every female folk singer-songwriter who has picked up a guitar since 1968, as well as pop, rock and hip-hop stars who openly pay tribute to her, including Madonna, Courtney Love, Norah Jones, Prince, Janet Jackson, Taylor Swift and Kanye West.

Mitchell’s earliest songs were the progenitors of “grrl power,” couched in soaring melodies and acoustic folk arrangements that, for an entire generation of listeners, made sorrow, heartbreak and angst feel beautiful while suggesting a new kind of female empowerment. Over the years, we have come to understand that the songs are highly autobiographical, strewn with details of her high-profile affairs with James Taylor and Graham Nash (both of whom returned the favor in their own songs), as well as with David Crosby, Jackson Browne, Warren Beatty, and the great Jewish bard of depression and loneliness, Leonard Cohen. According to Sheila Weller’s excellent rock history, “Girls Like Us,” Mitchell also had close relationships with several members of the New York City-based Blues Project, an almost all-Jewish band that included Steve Katz, Roy Blumenfeld and Al Kooper.

Jewish men figured strongly in both Mitchell’s personal life and her career. Early on she befriended Elliot Roberts (born Rabinowitz) and Borough Park native David Geffen, college pals who went on to steer Mitchell’s career through their management firm and their record label, Asylum. Mitchell immortalized Geffen in her 1973 hit song, “Free Man in Paris.”

Mitchell’s music veered toward jazz in the early 1980s, and one day a bassist named Larry Klein — the California-raised son of a Jewish aerospace engineer father and housewife — was hired for a session. The two hit it off, and began a long romantic and creative collaboration. Mitchell and Klein were married from 1982 to 1994, and Klein produced, co-wrote and played on Mitchell’s best late-career albums, including “Dog Eat Dog,” “Chalk Mark in a Rainstorm,” “Night Ride Home” and “Turbulent Indigo.”

Incidentally, after attending Hebrew school and becoming a bar mitzvah, Klein, a very spiritual guy, put Judaism on the back burner for many years, opting instead for Buddhism. Then one day in the early ‘80s, the actress Rebecca Pidgeon invited Klein to attend Friday night services with her and her husband David Mamet. Klein became smitten by the approach of the Mamets’ spiritual guide, Rabbi Mordecai Finley, and, in 2006, Finley officiated at Klein’s wedding to the Brazilian-born singer Luciana Souza, who, under Finley’s tutelage, had converted to Judaism, as had Pidgeon before her.

Other than Roberts, Israeli-born singer and writer Malka Marom is apparently one of the only friends Mitchell has stayed in touch with over the decades. A renowned misanthrope, Mitchell boasts about the pleasures of living as a recluse on her secluded property in British Columbia, and her songs of the past 30 years are filled with a delicious disgust for the human race. (In an interview with Marom, she refers to “my contempt for my species.”) Mitchell and Marom met in Toronto in 1966, and Marom has been one of very few writers to whom Mitchell has granted extensive interviews. These are collected in Marom’s book, “Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words.’ “I think Joni is Jewish,” Marom once said to author David Yaffe — who is himself working on a biography of Mitchell— “In her soul she is Jewish, even if not in her blood.”

Many of Mitchell’s iconic early songs made up a good portion of the soundtrack to Jewish summer camp sing-alongs in the 1970s, inspiring Jewish singer-songwriter Debbie Friedman along the way. “The Circle Game” is both a sing-along classic and a philosophical musing with a deeply Jewish message. A 1968 album by Tom Rush on which the folksinger recorded three Mitchell tunes, including “Urge for Going” and “Tin Angel,” introduced the singer to a wide audience. The title tune depicts life as a “carousel of time,” measured by “the seasons [going] round and round.” It’s a quintessentially Jewish notion of time, which measures the passage of years by communal recurrences (festivals, holy days) rather than by individual occurrences or milestones.

Mitchell has said that “Both Sides Now,” which Judy Collins first made into a hit in 1967, was inspired by a passage in Saul Bellow’s 1959 novel, “Henderson the Rain King,” about sitting in an airplane and looking down at clouds. The song lyrics embody a dialectical outlook on clouds, love, and life, in which perspectives are swapped so that the same thing looks totally different from another point of view. Mitchell’s approach here is talmudic, as if the Tannaim and the Amoraim are disputing the view from the ground and through the airplane window.

In the 1974 love song called “Jericho,” Mitchell used the story of Joshua as a metaphor for opening up one’s heart: “Just like Jericho I said, ‘Let these walls come tumbling down.’” Mitchell’s cynicism, however, gets the best of her when she predicts the relationship is doomed to fail, for which she invokes another iconic religious figure: “Or maybe it’s you/ Judas in the end / When you just can no longer pretend that you’re getting what you need.”

Mitchell returned to the Bible for the inspiration behind her 1994 song “The Sire of Sorrow (Job’s Sad Song).” At this point in her life and career, long past her critical and commercial prime, beset by illness and by a sense of personal and societal betrayal, she apparently identified strongly with the character of Job:

One can only hope that, for Mitchell’s sake, she has found some comfort in her recovery from illness and near-death. And as for those of us who hang on her every word, we can only hope that we haven’t heard the last from one of the great cynics, misanthropes and musical geniuses of our era.

Seth Rogovoy mines popular culture for the Forward, for the most unlikely of Jewish affinities.