After Havdalah, a Sense of Exile

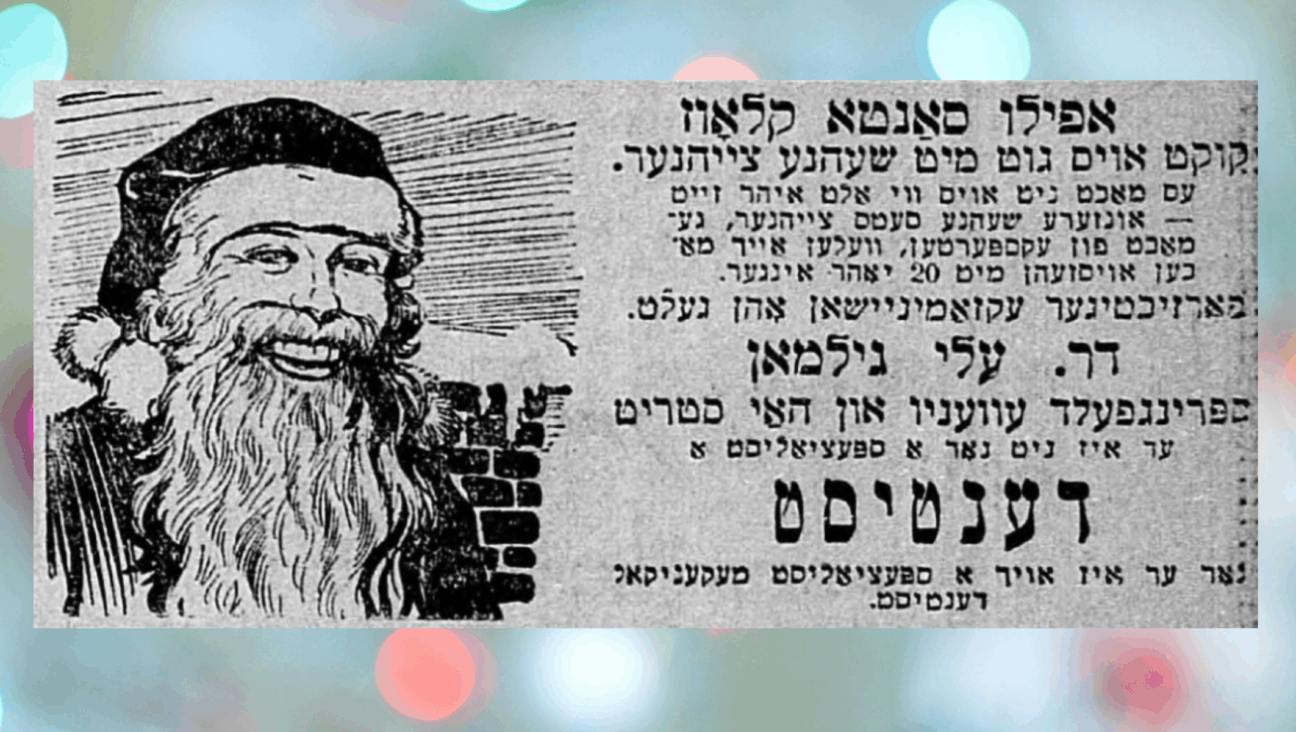

Image by Anya Ulinich

I remember, when I was 6 or 7 years old, a ritual: Immediately after Havdalah my mother would run over to the phone — a yellow rotary phone embedded in the kitchen wall, to call her parents. It was 1970 or thereabouts. We lived in Montreal then, and it was a long-distance call to New York City’s Upper West Side, where my grandparents lived.

I would listen from afar as she would stand chained to the wall by the coiled phone cord. (My grandfather boomed into the phone so that I could hear him through the receiver, even though I was half a room away.) It was a back-and-forth with Polish Jews, replete with malapropisms and a rapid, high-velocity word count. Mother would ask, “M’gait morgen tzu Miami.” Which airline? “Easter airline. — fun lugvardia.” “Which hotel?” “Vais ich nisht — a ’Holiday Johnson?’” There were the obligatory references to various physical ailments of family members. Then there was the cataloging of different relatives who were coming apart at the seams. Uncle Feivel had stomach cancer. He was in Memorial Hospital. Cousin Yoel had his gall bladder removed. A third one was in ganzen bankrateirt, gone completely bankrupt.

My mother would put her hand to her forehead as she listened. Sometimes, she would drag a chair from the kitchen table to sit on. There, with her head down low, she seemed to me like a small girl. It is always a strange concept for a child to realize that your parents have parents.

My father, who was always nearby, grimaced. I think for him this was a piece of Yiddish family theater he was left out of. Worse, it was proof that mother was more connected to her family than to him. Of course, this wasn’t the case at all; she was just like most of us, guilty of the sin of privileging the elusive past over the unbearable present. She never seemed happy after these calls, only pensive and restive as if the darkness of the past and the past of her parents was her glum but only reliable friend. In fact, the moment my mother got off the phone I could sense in her only scarce relief. I knew intuitively that though she had gone to a place that was utterly familiar to her, she had become lost to me and even to herself. She was now fit for nothing but rote tasks and sleep.

Why did she feel compelled to enact this ritual of somber duty and sadness every Saturday night?

After all, she had spent most of the Sabbath in the bosom of a loving family — resting, reading and of course eating. Though she herself ate little, the “house” could never have enough food for the Sabbath. The table itself had several different kinds of meats, and deli. My mother made for my father pastrami, salami and coleslaw, pickles, onions, egg salad. He would have beer (Heineken) in a frosted mug, and for dessert, big beer pretzels. Our dessert was some kind of goo we called pareve ice cream. It’s not that the meals were a foretaste of the paradisiacal afterworld, but during these meals the blur and frightening motion of the week was banished. There was a closeness between us siblings, and my parents that held the fragmented, even sinister world just outside our windows at bay.

In the half-hour leading up to Havdalah, I could feel the tension mount. It would get dark, not just in reality, but also inside. My mother would look at the clock on the wall. “Shabbes is practically over,” she would announce softly, as if something ominous were going to happen.

By Havdalah time it was as if an unwelcome guest would arrive, bringing with it an amalgam of the ghosts and spooks of Eastern Europe with an American topping of bills to pay and other unfair impositions on the Jewish people from a world that didn’t understand us. No sooner would we pass around the spices than she would make a beeline for the phone.

My experience of Sabbath’s end was, of course, much different. I greedily awaited the freedom to play with battery-operated toys that had flashing lights: police cars, fire engines and toy tow trucks. As we got a little older, my sisters and I embraced a ritual familiar to other Orthodox families: a television lineup that included “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “The Bob Newhart Show” and “The Carol Burnett Show.” My father, a rabbi who possessed not a trace of my mother’s poetic gloom, would make Jiffy Pop Popcorn on the stove and eat ice cream with us, but Mother was lost to us. It had the feeling of more or less permanent loss.

I got a glimpse at the root of this as I got older and got to know her mother. Die bubbe was a realistic, righteous woman who spoke in the measured tones of grief; short declarative statements, punctuated by “How’s fodder? Or, “How’s [your sister] Malka?” “Fine, fine, they are fine,” I would say. Long silences followed. Looking back, it was like talking to someone who perpetually sat on a low shiva stool but instead of the ritual sentence “May God comfort you among the Mourners of Zion,” it was followed by her reassurances, “Okay dahling, es is vet zein gut” — “It will be good.” Perpetual grief was sewn into the fabric of life.

But only when my mother told me the following story did I begin to get a clearer picture. During the war in London when she was four, she was evacuated to the countryside with her sister, who was a few years older. They were put on a train to Leeds with other children. At the station, various townspeople— utter strangers — would inspect them like plantation owners at a slave market until someone “selected” them. I think she was so terrified of being ”lost” that she resolved then and there never to willingly separate herself from anyone she loved. Although this gave her peace of mind on some level, because it was reflexive and unconditional and automatic it guaranteed a certain misery. Things couldn’t be worked out, because we always had to remain attached. It was as though she had the attachment muscle but not the separation muscle that one needs in order to have a truly successful life.

God, how I loved that woman! I didn’t know how much. She was kind and exceptionally beautiful, but it was not for those things that I loved her. It was her sense of predicament that I loved. To live in my mother’s world was to live in predicament. The predicament of living forever close to the young frightened child she once was — somewhat protected, but fundamentally unsafe — the predicament of being a Jew, durable yet totally vulnerable.

Now in middle age, for the first time in my life I am in no hurry for Sabbath to end. I work up a storm of Talmud learning throughout the Sabbath, reaching an apotheosis toward dusk. As the minutes tick by, I am aware of the ebbing of the day, and memories of my mother (already in the next world) come flooding back. I am filled with her foreboding.

In fact, I have begun to end the Sabbath later and later. Instead of rushing at the first moment like I did as a child. Havdalah means to separate. Perhaps I am not much different from Mother. I put off Havdalah as much as possible. I sit in the beit midrash, waiting for the last minyan with my hevruta, my friend, intoning the songs of the Talmud through the twilight and, finally, inevitably, into the oblivion and exile of the week.

Simon Yisroel Feuerman is a psychotherapist and director of the New Center for Advanced Psychotherapy Studies.