How To Make A Yiddish Classic When You Don’t Know Any Yiddish

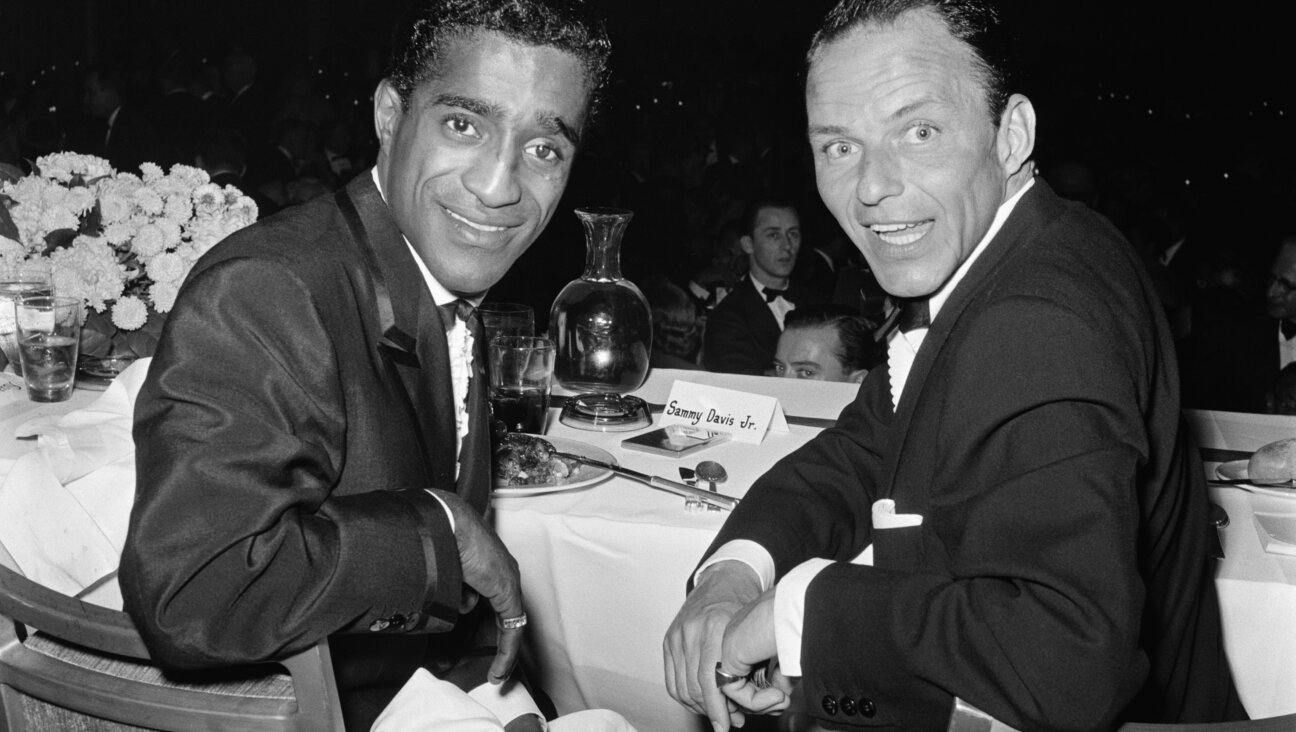

‘Menashe’ stars Menashe Lustig Image by A24 Films

Documentarian Joshua Z. Weinstein, 33, who dubs himself a humanist filmmaker, says he never wanted to make a Jewish movie, but rather one that explores the interplay (maybe the clash) between faith and modernity. It’s almost — but not quite — incidental that his characters are Yiddish-speaking Hasidim, members of the most austere sects living in the Boro Park section of Brooklyn.

“Menashe,” his theatrical film debut, is being billed as the first Yiddish- language film to hit the screen in more than 70 years — not including Eve Annenberg’s 2010 “Romeo & Juliet in Yiddish.” Most of the performers have never even seen a film, many don’t own televisions. They are practicing, observant ultra-Orthodox Jews.

In a Paddy Chayefsky “Marty” vein, “Menashe” (slated to be released on July 28) tells the disturbing story of a round, childlike widower (loosely based on the experiences of its star, Menashe Lustig) who is forced to relinquish custody of his young son, Rieven (Ruben Niborski), because Hasidic tradition dictates that a child be raised in a home with a mother or surrogate mother. If Menashe refuses to hand over his son to his married brother-in-law, Eizik (Yoel Weisshaus), a condescending prig who holds Menashe in utter contempt as a bumbling, inept fool, the child may be expelled from his yeshiva.

“I wanted to explore the nature of faith and how it affects someone,” said Weinstein, who met me on 13th Avenue, in a noisy Boro Park restaurant filled with head-covered women (some accompanied by babies in strollers) and flanked by aging tenement buildings boasting Yiddish signage. It was a few blocks from the massive rusting El on 51st Street. Much of the shooting took place on these streets.

“I love the fact that these people are uninhibited by modernity. They speak their minds. With the advent of modern technology, something has been lost throughout the culture. Eccentricity has given way to homogeneity. There are fewer clearly marked regional accents. But here, in this community, there’s still something unique, and I respect that.” Weinstein said. He gestured at the yarmulke on his head: “I never wear it. But I do when I come into this neighborhood. It’s a sign of respect.”

Best known as a cinematographer on documentaries, Weinstein was looking for a project that was serious but not so dark that he wouldn’t be able to sleep at night.

His fascination with Brooklyn and its ultra-Orthodox population dates back to his childhood, when he visited and later worked at his grandfather’s toy store (the iconic Red’s Warehouse Outlet in Mill Basin and Canarsie).

More recently he moved to Crown Heights (admittedly the Caribbean section), but he spent much of his free time walking around those religious enclaves that only captivated him further with each exposure — from Crown Heights to Boro Park and beyond, to communities in upstate New York. He was drawn to the characters, an amalgam of messy contradictions who also spoke to his nostalgia, evoking the friends, acquaintances and neighbors of relatives he recalled (or perhaps re-imagined) from childhood.

“Their rituals, spectacles and celebrations were wonderfully mystifying,” he said. “What I found was so opposed to the usual narrative presented in the New York Post, with its descriptions of molestation within the Hasidic community and organs being sold on the black market. I wanted to create a film that showed the community’s complexity and nuance. It had never been done. Boaz Yakin’s ‘A Price Above Rubies, or Sidney Lumet’s ‘A Stranger Among Us’ is not a valid example).”

To be fully authentic the film had to be spoken in Yiddish. The problem was that he knew no Yiddish, short of a few phrases picked up from his grandparents. Attending a Conservative Jewish day school, like many post-World War II American Jewish youngsters, he learned Hebrew.

The first time he learned Yiddish was on the set. He realized there were many different Yiddish dialects, which is why he set his story in Boro Park, as virtually every Yiddish dialect is spoken there.

“That didn’t stop the actors from arguing over pronunciations,” he said. “You know the old joke about how many Jews does it take to change a lightbulb? They directed each other and had opinions about acting techniques, close-ups and appropriate lighting.”

•

The story of “Menashe” evolved from Weinstein’s interviews with the actors who recounted their lives and experiences during their auditions,. The actors informed the narrative, and roles were written or reconceived based on the actors who had been cast.

Casting was largely achieved thanks to the efforts of Danny Finkelman, a music video producer who served as a conduit to the community and knew the potential pool of actors, including Lustig, a comic whose Yiddish-language YouTube clips and videos are enjoyed throughout the Hasidic world.

Weinstein felt an immediate rapport with Lustig, whom he found to be an incredibly funny, loving human being and a great deal more independent-minded than one might suspect. “He has his own ideas and is not constantly conferring with his rabbi,” Weinstein said.

And his personal story was both unique to a world with its own worldview and rules and also widely relatable. “It was just what I was looking for,” Weinstein said. “The big challenge was to bring the acting all the way down. Nobody had acting training, and if they had done any acting at all it would have been in one or two of the school productions that the yeshivas produce each year, and the acting there is big and comic. Menashe didn’t believe an audience could possibly find small dramatic moments on screen interesting.”

Writing the script first in English (to be followed by its Yiddish translation) started with a loose storyline and some bits of dialogue. That led to improvisation, which in turn led to a script. Far more complicated was casting men and women in the same film, though there are few women in this story. Weinstein gently evokes the insular, patriarchal society, with the notable absence of women at the cemetery and memorial, and, in one snippet of background conversation, a father dismissing his daughter’s desire to go to college as just plain silly.

Still, in one memorable scene a woman is front and center as a widow facing Menashe across a table at a restaurant. They are on an arranged date for the purpose of determining whether they’re compatible enough to get married. The scene, with its implied mating rituals, is fascinating in and of itself.

But more to the point it would appear the actor and actress are in the same frame, and strictly speaking, this is forbidden unless the actors in question are married to each other or otherwise blood related. Weinstein refused to say if the guidelines were violated or if some trick photography was involved. Instead, he likened himself to a magician who doesn’t want to reveal the how-to of his magic.

Weinstein knows that the most religious members of the community will not see the film, which leads to a couple of obvious questions: Who will see it, and what will the film be saying to them? Weinstein says he’s not remotely concerned that his film will in any way confirm anti-Semitic tropes or stereotypes, or, worse, foster a new batch.

“No, I never worried about stereotypes,” he said. “You’re only doing stereotypes if you don’t explain them. No action in the film is unexplained. I give the audience the tools to understand what it’s all about, the shades of gray. Stereotypes are just cheap art. If you’re not doing cheap art, you’re not doing stereotypes.”

Weinstein was both insider and outsider — empathic and judgmental, embraced and distrusted. And, all these seeming paradoxes gave him a fresh perspective. In the end he had astonishing access, including joining a rabbi in a mikveh. “National Geographic never made as accurate a film about the Hasidim,” he said.

•

Weinstein worked on spec. He shot a few scenes and ultimately attracted the attention of larger investors, including Maiden Voyage Pictures, the production company co-founded by “Mrs. Doubtfire” director Chris Columbus.

But that didn’t solve all his problems. All the actors held day jobs (like his on- screen alter-ego, Menashe works in a supermarket); there was no rehearsing on Friday evenings or Saturdays, and daily accommodations had to be made for the actors who prayed three times each day. To make matters more difficult, a few performers dropped out well into the shoot, deciding that the pushback from their synagogues wasn’t worth it, and replacements had to be found.

Quagmires were everywhere, whether the team was attempting to set up a shoot on the street or in a commercial space, like a restaurant or supermarket. “Managers or owners did not und erstand why they had to sign contracts, or the fact that the filmmakers needed 10 hours to shoot a one-minute scene,” Weinstein said. “And if the owners, usually the grandfathers, live in other countries the managers might not be able to reach them quickly. Not everybody uses emails or texts. They didn’t have any particular incentive to turn off their radios or move customers aside to accommodate filmmakers. For one supermarket scene we ended up shooting in four different supermarkets.”

Interestingly, the filmmakers encountered no hostility from the residents on the streets. On the contrary, onlookers were “fascinated, enthusiastic and enjoyed the proceedings,” Weinstein said. “They didn’t have any desire to be in the movie but wanted to talk about it.”

There were also those who simply couldn’t grasp the idea of moviemaking as a professional or serious activity.

“In the middle of filming, a guy on the street who knew Menashe interrupted the shoot,” Weinstein said, “walking right into the scene as the cameras rolled to ask if he was going to Monsey that night and if he was, ‘Could I give you a box that you could take for me?’ The man had no boundaries. He saw the cameras and lights and just didn’t care.”

After “Menashe” was completed and had its first screenings, the experience was as revelatory for Weinstein as it was for his star, who was seeing a movie for the first time — and playing its title character vaguely inspired by his own life. During the course of a lifetime Lustig never had his feelings, experiences — indeed, his entire being — as validated as they were at that moment. To judge by his expression it was both thrilling and troubling kindling a host of mixed emotions, Weinstein recalled.

“No, I don’t think he wants to leave his community,” he said. “He’s not a bomb thrower. He wants to change the community from within and is now talking about creating a new industry of Yiddish-language films set in the Hasidic world. I think it’s great. As an artist I’m interested in anything that makes the world a smaller place. I’ve always felt that. But I feel it now stronger than ever.”

Simi Horwitz was a 2016 Deadline Club finalist for a series of stories she wrote for the Forward about Orthodox Jewish women pursuing careers in the arts. She also won a 2016 Rockower Award for a feature story about frum filmmakers.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO