Found in Translation: A Round-up

Language, our first barrier, now also seems our last. Babel is one bookend of human communication; today’s instantaneous transmission of Babel through a baffling array of technologies is the other. Perhaps one of the oldest occupations, after the making of towers, is translation — that utopian and often invisible task of making one word mean another is now more important than ever: important politically, socially and, as a means of enriching our native expression, important aesthetically, too. Allowing us to know worlds outside our own, any translation is an attempt to go beyond this last bookend, an ingathering of all Babels both technologically literal and existentially metaphoric, becoming a preview of the once and future Eden, in which, according to midrash and the Prophet Zephaniah, we will all speak the same language again.

At a time in which our lives have become commercialized against the very necessities of translation and its appreciation, it seems vital to celebrate, while critiquing, the little foreign literature that does make it into our print: to celebrate it as essential to any truly global future. Jews have always lived singular lives in multiple languages; if Jews in America are to retain for any future whatsoever the perspective of this inheritance, we must be sure not to write the final page of this chapter. In this spirit, we offer the following: reviews of five titles, all written by Jews or written about them or both, recently translated from the Czech, Dutch, German and Hungarian — Jewish languages, all. — Joshua Cohen

The Circumcision By György Dalos Translated by Judith Sollosy Marion Boyars Publishers 140 pages, $14.95

“The Circumcision” is two procedures: One involves the separation of foreskin from penis; the other is a separation more metaphysical: the estrangement of Robi Singer from the religion of his birth.

At 8 days of age, Robi never had a bris; the oversight was a “vis major,” an act of God. Divinity aside, another explanation of the period, and of the failure of many to circumcise their children, is offered: Hungarian fascists were in the habit of ordering fellow citizens to “drop their pants to check whether they were Jews walking around without their yellow stars in violation of the law. When anyone was caught, he was promptly marched down to the Danube and shot into the icy river. Well, she had no intention of having her grandson caught with his pants down.”

This “she” is Grandmother, a former employee of the Kerchief Dyers’ Cooperative, mother to Erzsike, who’s been a medicated wreck since the death of Robi’s father. Single-mothered, then, Robi, age 12, lives during the week in a Jewish orphanage that demands his circumcision in preparation for becoming a bar mitzvah. He’s torn, afraid of the procedure; he’s afraid, too, of what it means to be Jewish, and so he seeks identity as a Hungarian, in communism and in Christianity, at a church that evangelizes to the remnant of Budapest’s Jewry.

Born in Budapest in 1943, victim of arrests, censors, a ban on publication, György Dalos is a master of all that’s literally, and literarily, Eastern. Having been stateless, without a people, Dalos’s only law is humor, his liturgy the one-liner. Ensuing circumcision circumlocutions evade what’s become expected in this manner, though, by refusing Robi any salvation — even that of Jesus, who, though a Jew and a communist, was certainly no Hungarian.

One complaint. Though Judith Sollosy’s translation is fluent, the mistakes in her footnotes, especially those on the German, are strange. Her “scholet,” a transliteration of the Hungarian sólet, should be “cholent.” The Appelplatz is not “the infamous big square in Berlin where the Nazi book burnings took place” but rather the mustering grounds of a concentration camp, here Auschwitz.

Secretly Inside By Hans Warren Translated by S.J. Leinbach Introduction by Jolanda Vanderwal Taylor The University of Wisconsin Press *80 pages, $16.958

To conflate hiding from the Nazis with a homosexual hiding his or her orientation, even in an age less open than ours, would be artistically disastrous for a lesser writer than Hans Warren. Survival must precede sexuality. One must be alive before one may profess love, or lust.

In Warren’s newly translated “Secretly Inside,” written in 1975, which was the year that Warren left his family to publicly declare his homosexuality, a Jew hides from the Nazis in the Dutch countryside. While attempting to pass as a farmhand he finds his heart, and that of the son of the family with whom he lives.

Eduard van Wyngen arrives in the village of Kruisdrope to be hidden by the Van ‘t Westeindes, impoverished Roman Catholics. He rooms with the son, Camiel, fresh from a relationship with a “Kraut,” a German officer who is mysteriously found dead on family land, stripped naked, lipstick on his lips. As the daughter, Mariete, attempts to seduce the hero (whose name, Ed, echoes that of the writer, Hans, with Wyngen standing in for Warren, the “van” a pretense that raises the hero, though Jewish, to the social standing of his hosts), Ed and Camiel become close; the consummation of their love would mean a crisis within a crisis. All nations develop literatures peculiar to the tenor of their wartimes. One Dutch contribution might be called the “hiding narrative,” the literature of the secret annex. Unable to fight Occupation (air war decimated Dutch naval superiority; the Low Countries fell in four days), a Holocaust literature that saved Dutch face had to be focused not on the glory of resistance but on the more mundane victory of evading capture. Undoubtedly, this genre’s exemplar is the diary of Amsterdam’s Anne Frank, later reworked to achieve more dramatic form by her father, Otto. “Secretly Inside” is at once its memoir heir, and a fictional subversion; with any capacity for sensationalism converted to naturalism, in Warren’s presentation of homosexuality as a fact manifesting equally among the impure (Jew), the pure (Nazi) and those who might metaphysically mediate between the two (Camiel).

Novels in translation often lead their own hidden lives. “Secretly Inside” was originally called “Steen der hulp,” or “Stone of Help,” after the scriptural name of the Van ‘t Westeindes farm. This title is immensely preferable to the more filmic and ultimately glib “Secretly Inside” — speaking to the occasional misjudgment of the translation, or to the difficulties in interesting America in foreign literature. Let it be no secret that Warren deserves better, and his readers do, too.

Fire on Water: Porgess and the Abyss By Arnost Lustig Translated by Roman Kostovski and Deborah Durham-Vichr Northwestern University Press 248 pages, $16.95

Be fruitful and multiply is the exhortation of Genesis; replenish the earth, and subdue it. Auschwitz prisoner, Resistance hero, Soviet exile, master novelist and editor of Czech Playboy, Arnot Lustig reminds us that this dictum has become more important than ever following the tragedy to which he bears witness.

The eponymous character of Porgess, the first novella in “Fire on Water,” “looks likes an Aryan”; he was once “the most beautiful boy in Jewish Prague.” On the war’s last day, he is shot in the spine, twice. He survives with two pains, that of his wound and that of its irony: So close to freedom, he’s paralyzed, rendered impotent and reliant on the care of his mother.

Obsessed with kabbalistic numerology (three is good; Porgess escaped three Selektionen), the sensual music of jazz (three, the triplet, is the musical unit that swings the most) and the women they knew before the war and in the camps (“She flew through the chimney as a virgin, though no one would think so, the way she had developed: full breasts, hips, and a maternal smile”), “Porgess” is composed of these familiar, even familial, conversations with the Lustig-like narrator, a journalist and fellow survivor. An indomitable dialogue of set-ups, hilariously humorless, their punch lines come only as bullets.

In “The Abyss,” the survivor’s testimony is grimmer. Now a Czech soldier, David Wiesenthal patrols the mountainous border with Germany. There, women from his past begin appearing to him, haunting with unrealized eros. Even in fantasy, sex comes hand in hand with the promise of continuity; the idea of resurrecting a people gives duty to pleasure.

Wiesenthal ends with a Virgil-less descent into Dante, as he encounters that most mystically heretical of entities, a Jewish goddess: a resurrected Beatrice who is all flesh, whose hair has grown back from being shaved, whose figure has been returned to her from starvation. What follows is a rewrite of all European love literature, a “Divina Tragedia” in which there’s no passion to mourn, or sacrifice to glorify, only the pain of losing what could have been but never was.

The Golem A New Translation of the Classic Play and Selected Short Stories Edited and Translated by Joachim Neugroschel W.W. Norton & Company 352 pages, $25.95

Talmud tells us that Rava, in the fourth century of the Common Era, created a man and then sent him for inspection to Rabbi Zera, who promptly turned this golem to dust. Jewish literature’s first manmade humanoid, a mud lump made sensate through the invocation of a magical Shem, or name, was short lived, especially when compared with the enduring infamy of his, or its, kind. “The Golem” under discussion here is a golem itself, a fascinating construction if not of clay then of texts, earthy and grave, that range from a new translation of the famous Yiddish play by Leivick Halper to little-known selections from the work of Yudl Rosenberg (1860-1935), Solomon Bastomski (1891-1941) and David Frischmann (1859-1922).

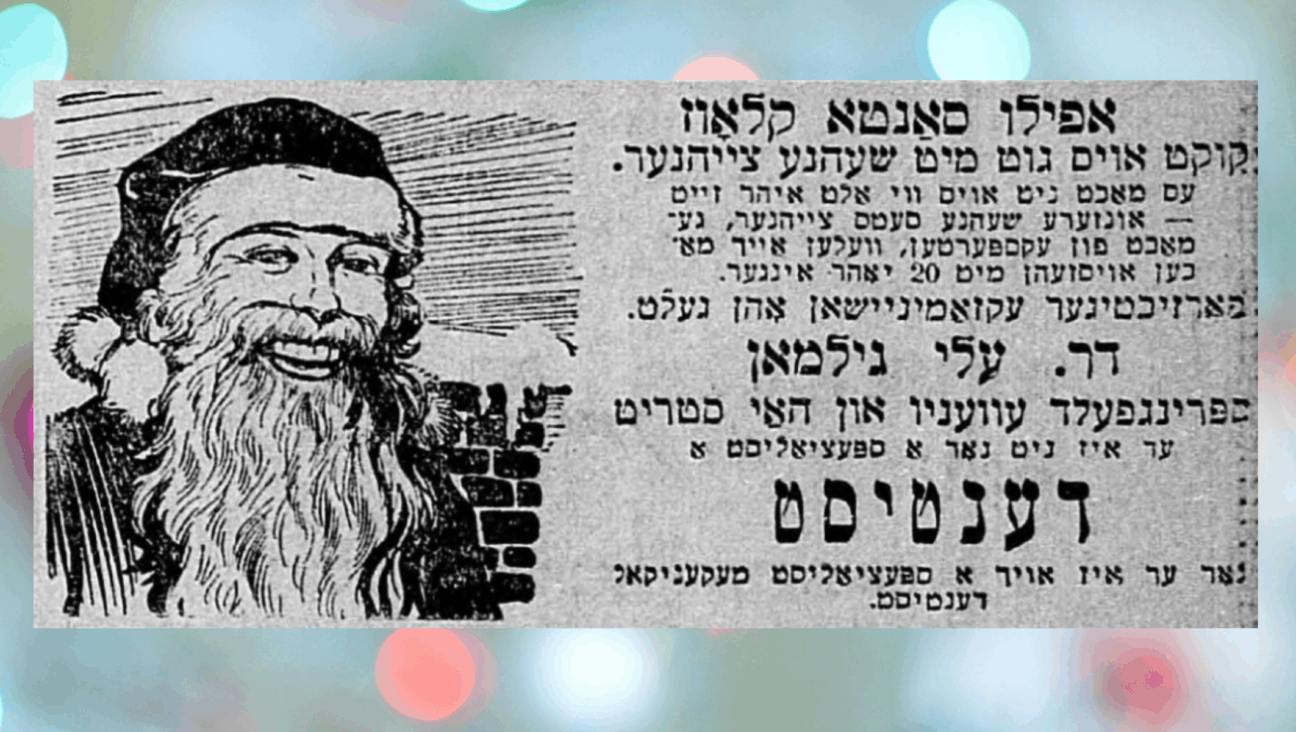

Focusing as it does on Yiddish, this volume enacts the passage of the golem from the realm of Kabbalah and Talmud to that of popular folklore and literature: These are stories told not as parables, or for purposes of moralizing, but for entertainment; made for the same reason that many golems were made: to liberate Jews from the soul-destroying realities of ghetto life. In these pages, blood libels are averted, cardinals are disputed; proto-robots are wined and dined at the court of crazed Rudolf II, the Holy Roman emperor.

Of all the stories and stories within stories here, Halper’s is still the attraction, towering above its thematic peers and predecessors, which include Gustav Meyrink’s novel and Goethe’s fantasia “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” After surviving all that Europe and Russia had to offer: pogrom, war, a stint in Siberia, Halper’s posterity was to fashion the ultimate Jew, a Jew among Jews. As the Jew suffers for the world, the tautology goes, the golem suffers for the Jews. “The fire hasn’t consumed me, the rocks haven’t felled me.” Only Halper is left to suffer for the golem, and the result is a masterwork of dark defiance.

Boys & Murderers By Hermann Ungar Translated by Isabel Fargo Cole Twisted Spoon Press 252 pages, $15.00

While the comparatively staid contributions of Paul Kornfeld, Egon Erwin Kisch and even Franz Werfel have been consigned to the purgatory of the not-yet-forgotten though rarely read, two “Academies” have managed to report back to our literary present from the genius that was last century’s Prague German. One Academy can be called “Kafka,” to be safely interpreted by its own parodies. The other Academy is far less famous and far more unruly: It might be called “Decadent”; it’s certain that its chief exponents were Paul Leppin and Hermann Ungar.

Leppin, whose books are also published by Prague’s Twisted Spoon, was what we’d now call a “personality,” a self-styled Bohemian in Bohemia, an absinthe drinker with a penchant for prostitutes, a late-night denizen of the dilapidated Jewish ghetto around Maiselova Street. Ungar, a transplant from Moravia, was less revealed; a professional bureaucrat at one time employed at a bank, and a visionary who often underwrote his horrific preoccupations (incest, deformity, the decline of Empire) in the interests of classical brevity.

Having written an astounding novel, “The Maimed,” as well as these and other novellas, stories and plays, Ungar died in Prague in 1929 at the age of 36. His work was posthumously praised, notably in a short essay by Thomas Mann, which is included here as a preface in its debut translation. Its title less Freudian than factual, a bald statement of theme, “Boys & Murderers” is obsessional literature, harrowing and pitiless. In its first story, “A Man and a Maid,” a boy leaves his orphanage for America, where he endeavors to make a fortune, only to return to his Moravian town (based on Ungar’s native Boskovice) to enslave the orphanage’s charwoman, whose sexuality so preoccupied his childhood. Other stories similarly confront a world in adolescent decay, a modernity beset with the basest desires: Ungar’s people are almost invariably nymphomaniacs and killers, soldier-drunkards humored by the occasional barbering hunchback. In these pages, there’s little history to parse, and hardly any psychology. Topos matters little; the names may change, but we stay the same — our demons follow us everywhere.