Was Alan Gershwin Really George Gershwin’s Son?

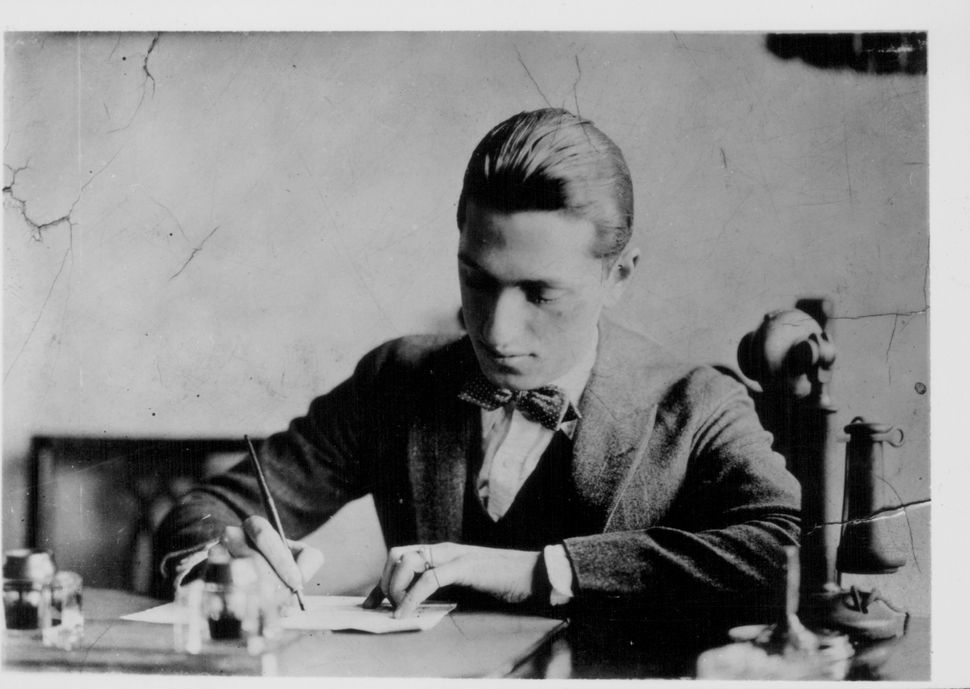

George Gershwin Image by Getty Images

Brooklyn-born Albert Schneider, who called himself Alan C. Gershwin, maintained the claim that he was an illegitimate son of the American Jewish songwriter George Gershwin (1898-1937) for decades until his death on February 27 at age 91. He never relented, despite the Gershwin family’s prompt denial of any such connection. Schneider/Gershwin, as he shall be called here to avoid confusion, asserted that his mother was Mollie Charlkovitz, a chorus girl who performed under the name of Mollie Charleston, after the name of a popular dance of the 1920s. No serious claim on the composer’s royalties ever ensued, despite occasional warning salvos in the popular media. A modest, although quietly persistent, claimant, Schneider/Gershwin never proved his purported origins with a DNA test. This would have definitively resolved any lingering mystery, as Gershwin biographer Howard Pollack pointed out. Schneider/Gershwin, an aspiring songwriter, also claimed to have co-written the Elvis Presley hit “I Want You, I Need You, I Love You,” (1956) but was denied his rightful credit by its authors, Maurice Mysels and Ira Kosloff. No legal challenge about authorship of the ditty was ever made either. Schneider/Gershwin appeared to prefer uncertainty, where a level of doubt might remain, at least among the credulous.

These included at least one historian, Harold Holzer, author of books on Abraham Lincoln. Holzer told the New York Times that when he met Schneider/Gershwin around 2009, his reaction was: “My God, it was George Gershwin as an old man. That protruding lower lip — no one has that face but George Gershwin.” Holzer’s physiognomic analyses of the portraits of Lincoln should have made him an expert at this kind of facial matching. Holzer was serving as a consultant on Schneider/Gershwin’s most visible public commission, The Gettysburg Anthem, a setting for solo tenor and ensemble with organ accompaniment of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. It was performed in 2009 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D. C., and later heard in New York and Florida. Written several years before its first public rendition, “The Gettysburg Anthem” is a stagnant work, revealing no sense of how to set words. A murky sound texture, accentuated by spooky organ accompaniment that is half “Phantom of the Opera,” half down-at-the-heels ecclesiastical, adds further disappointment. Schneider/Gershwin’s other legacy as a musician was a recording of his songs by the Men In Black barbershop quartet, a group from Hartford, Connecticut. Despite this relative obscurity, Hanspeter Krellmann, a German musicologist and authority on such composers as Busoni, Webern, and Grieg, remarked in a book on Gershwin that Schneider/Gershwin possessed an “astonishing facial resemblance to the composer.”

In addition to resemblance, an ingratiating personality was surely part of the credibility of his claims. Schneider/Gershwin cheerfully autographed photos, posters, and even souvenir editions of postage stamps bearing Gershwin’s image. In the 1980s, Schneider/Gershwin had an image measuring 4 x 6 inches printed juxtaposing his profile in younger years with Gershwin’s, suitable for autographing. He gave lectures on cruise ships, attended Gershwin performances as an honored guest, and in October 2004, used his supposed VIP status to get press coverage when his companion Blossom Tracy was unhappy with treatment she had received at the N.Y.U. Dental Clinic.

Schneider/Gershwin also kept up an energetic correspondence with celebrities, attempting to win believers to his side. One example is posted online by the Pittsburg State University Special Collections department. Dated February 1978, it is a letter addressed to the African-American choir leader Eva Jessye, co-music director for Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess (1935). The message manages to be vague and friendly at the same time, with enthusiasm expressed by an abundant use of exclamation points. An initial wrong spelling of the last name of Jessye, whom the message suggests “may have” heard about the writer, is corrected. There is a plain statement of his supposed paternity, followed by the information that this fact has been hushed up for a long time for reasons “that cannot be discussed too freely.” The note further explains that he obtained her address from the blues singer Katherine Handy Lewis — misspelling her first name — daughter of the composer W.C. Handy, known as the Father of the Blues. With a final uncertainty, he suggests that he “may have” met Jessye just after the New York premiere of “Porgy and Bess.” In the library catalogue, the Pittsburg State item is annotated: “Alan Gershwin was the son of George Gershwin.”

As archival collections are increasingly digitized, more such missives may turn up. Further correspondence is housed in the Institute Jobim in Brazil, There, a postcard from Schneider/Gershwin showing an image of George Gershwin was mailed in December 1985 to the composer Antonio Carlos Jobim. It offers the latter best wishes for a successful career. An archival note comments: “The signer is the son of George Gershwin.”

These mentions may provide the best persuasion for the unlikely story, as previous Gershwin biographers Charles Schwartz and Joan Peyser who took the allegations seriously fade from memory. More recently, the novelist Nicholas Delbanco produced a study of young achievers, claiming that Gershwin’s “single known child was illegitimate, a son born to a chorus girl,” although allowing that “there are those who question the veracity” of the claim.

Earlier venues where the story appeared were unreliable. In June 1957, the American Jewish gossip columnist Walter Winchell, under a cloud because of his vehement support of Senator Joseph McCarthy, ran a blind item that a challenge to the Gershwin estate would be forthcoming from “an interpretive dancer’s son.” Although this never materialized, in 1959 the gossip bimonthly Confidential, ran an exposé of the supposed paternity case. After losing lawsuits by libeling celebrities, Confidential had been newly acquired by the publisher Hy Steirman, who must have seen Gershwin as fair game, being safely dead.

Sifting through the nebulous details expressed over the years, one finds echoes of the story of Emerich Juettner, a counterfeiter who managed to evade capture for a decade until 1948 by only falsifying money in small denominations. Filmed in 1950 as Mister 880 starring the endearing character actor Edmund Gwenn (Santa Claus in “Miracle on 34th Street”) as the forger, the film showed how by keeping claims within reason, it is sometimes possible to get away with a charming, humble shvindel. Whether or not this applied to Schneider/Gershwin remains to be established for certain.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.