Among The Treasures Of The Bund, Lessons For Today

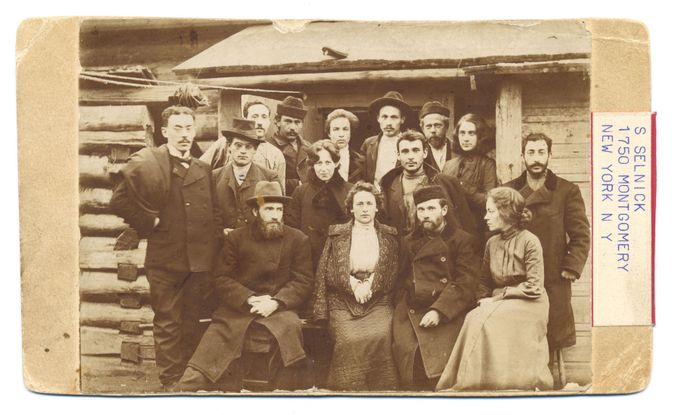

On The Streets Of Warsaw: A May Day 1936 Bund demonstration. Courtesy of the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Image by Courtesy of YIVO

The New York-based YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, which has held the fragile archives of the Bund since 1992, has announced a new initiative to make them more accessible to scholars and family researchers by digitizing and posting them online. Irene Pletka, the vice chairman of YIVO’s board, is kick-starting this effort with a reported pledge of $1 million, and after a $2.5 million to $3 million goal is reached, the institute will begin the first phase of digitization covering some 219 linear feet of records. In archivist jargon, 1 linear foot translates into 5,000 pages.

The Jewish political party, founded underground in 1897 in Vilna (today’s Vilnius, Lithuania), championed not only a broad progressive agenda but also physically confronted pogroms and resisted the Holocaust. YIVO describes the Bund as “a Jewish political party espousing socialist democratic ideology as well as cultural Yiddishism and Jewish national autonomism.” To CUNY political science professor Jack Jacobs, who twice has been a visiting professor at YIVO, it was the first modern Jewish political party in Eastern Europe. As a mass movement the Bund lasted for just the first four decades of the 20th century, he said. But its influence extended across the globe — and has lingered long after that, spilling over into other organizations that Bundists became involved in.

In its early years, a time of “dramatic urbanization among East European Jews,” the Bund focused on organizing unions and strikes and circulating radical literature (even arranging secret libraries) to raise workers’ consciousness about economic exploitation and political subjugation, Jacobs told me by phone and email from London. “Its bastions were cities like Warsaw, Lodz, Vilna and Bialystok,” then part of the Russian Empire.

By the early 20th century the Bund “played an important role in defending Jews from pogroms in the Russian Empire,” by setting up self-defense groups, Jacobs said. “When word got out that a mob was about to descend, the Bund mobilized its members and supporters … to physically confront the pogromists,” who sometimes were not highly organized and ran away when challenged.

“And the Bund’s response to anti-Semitism is, shockingly, very relevant to current concerns,” he added.

The Bund assumed a critical role in the 1905 Russian Revolution, calling on Jews to join with other socialist movements in a bid to overthrow the czar and thus attain political and economic rights, Jacobs said. Along with this, the Bund issued a singular demand, for “national, cultural autonomy so that Russian Jewry could control its own cultural and educational institutions.” Nonetheless, after the 1905 uprising was suppressed, many Bundists fled the Russian Empire.

Although Bundists supported the successful February Revolution in 1917, the ascendant Bolsheviks of the ensuing October Revolution posed ideological problems for them, prompting still more to flee, to Poland or other places, Jacobs said. Ultimately the Bund party in Russian lands fractured into two: One wing, still loyal to the Bolsheviks, was ultimately subsumed into the Communist Party; the other was banned.

After Poland gained its independence in the wake of World War I, the Bund could operate there legally and “blossomed,” creating in the 1920s and ’30s a “constellation” of allied secular cultural and educational groups that catered to women, children, young people and sports enthusiasts, Jacobs said. In the 1930s Bundists even staged successful campaigns for municipal posts, becoming the most powerful Jewish political party in Poland’s largest cities, he added. (In the last election in Warsaw before World War II, the Bundist-dominated ticket scored more seats on the city council than any other Jewish party.) But after Hitler and Stalin signed their nonaggression pact in 1939, the Soviet Union took over half of Poland and decided to wipe out the remnants of the Bund, YIVO’s executive director Jonathan Brent said.

During World War II, Bundists significantly participated in resistance activities, with Marek Edelman serving as a leader of the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto uprising, according to Jacobs. Ultimately, like millions of Jews in Eastern Europe, Bundists perished due to the war or Nazi atrocities.

Throughout the 20th century as Bundists scattered across the world, they created Bund-inspired organizations. And after the Polish Bund was liquidated in World War II, they created new branches of the Bund, said David Slucki, a Jewish studies professor at the College of Charleston. Indeed, one of the Bund’s “guiding principles is this idea of doikayt, which translated literally means here-ness” in Yiddish, “about kind of developing Jewish communities and responding to circumstances in the places where Jews lived,” he said. Thus those who immigrated to America poured their energy into the Workmen’s Circle, the Forward and the labor movement: Bundist émigré David Dubinsky presided over the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union; Sidney Hillman led the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America; and Baruch Charney Vladeck founded the Jewish Labor Committee and served as a New York City Council member as well as the Forward’s general manager.

The Paper Trail

Scene From a Rally: Vilna, 1936. Courtesy of the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Image by Courtesy of YIVO

Like the organization itself, the Bund’s archives have surfaced in many countries. By the end of World War I the Bund had moved its archives from Switzerland to Berlin and then, when the Nazis prevailed, to Paris. The Nazis seized the Bund’s archives during World War II, but after German forces were in retreat from France, the archives were deposited by a railroad station. With only portions recovered, the archives landed in New York in 1951 and were kept by the World Coordinating Committee of the Bund at the Atran Center on East 78th Street until YIVO acquired them in 1992.

Today within YIVO’s 23 million-document collection, the Bund’s total 800 linear feet of records include the organization’s own files as well as voluminous material it collected about other labor and kindred groups. The records are in Yiddish, Russian, Polish, Hebrew, English and French, as well as other languages. Currently the handwritten or typed finding aids are not available on the internet, said Stefanie Halpern, the assistant director of YIVO archives. When the digitization process is completed, YIVO will post online an enhanced, more descriptive finding aid for each asset, with a hyperlink to an image of it.

On October 31 of this year, Pletka and Brent visited a major Russian federal archive in Moscow to explore if about 35,000 pages of Bund archives held there could be digitized as well, thus uniting the archives online. “If this could come about, it would be a truly new important effort in American-Russian cultural cooperation,” said Brent, who first learned about this Moscow cache three years ago. This would “reunify in a single digital web platform, not physically but digitally these once coherent collections of materials.”

Brent shared why Russian cooperation on the digitization would be remarkable: The archival record “tears open so many of the wounds of the 20th century… and the acrimony and internecine fighting among the various competing socialist parties of Eastern Europe and Russia and that the Bolsheviks hated other socialist parties almost more than the fascists or the capitalists for that matter,” he said.

Archivist Leo Greenbaum, who has worked with the Bund’s archives in New York since 1978 even before they landed at YIVO, said the party’s early illegal revolutionary publications were created in secret shops in Russia or printed on thin sheets of cigarette paper in Switzerland and smuggled in. Small pamphlets could be fit easily into a pocket, ideal for discretion. Bundists also reproduced handwritten flyers in Yiddish, Russian or Polish with a hectograph, whose gelatin surface transfers ink. Some Bund publications remain folded up, Halpern said. “We have to unfold them, find out their contents, conserve them, then digitize them.”

Promoting Physical and Political Health: Children of the Miedzeszyn Medem Sanatorium near Warsaw. Courtesy of the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Image by Courtesy of YIVO

For Jacobs, one Bundist treasure is Aleksander Ford’s 1935 film “Mir Kumen On” (released in English as “Children Must Laugh”), which shows life at the Medem Sanatorium near Warsaw where its young residents perform “Lialkes” (Puppets). The Bund-run Medem Sanatorium aided children at risk for developing tuberculosis, “providing a progressive education [and] teaching values” as well, he said. Indeed, “the plot of ‘Lialkes’ revolves around a group of puppets, who ultimately learn that they are not powerless by rebelling against those who pull their strings,” said Jacobs, who cited the film and the play in his book “Bundist Counterculture in Interwar Poland.” Sound recordings from the film and its script are in the Bund archives.

Jacobs also referred to two archival sets as “compelling” for the general public to view: The first covers the activities of Bundist Shmuel “Artur” Zygielbojm, one of two Jewish representatives to the Polish government in exile who carried out his drastic 1943 suicide as wake-up call to the Allies to halt the Holocaust. Another shows the futile campaigns to save two prominent Polish Bundist leaders Henryk Erlich and Victor Alter, who were arrested and interrogated by Soviet agents multiple times and died in captivity. This file includes letters between Eleanor Roosevelt and Erlich’s son, Alexander, during the time of Henryk’s second arrest, according to Halpern.

Slucki relied on the Bund archives for his book “The International Jewish Labor Bund after 1945,” which he said pushes back on the idea that the Bund’s postwar history would inevitably be one of decline. He found richness in the World War II dispatches of the American Representation of the Bund in Poland, sent from London with smuggled-out information about what was occurring on the ground. The reports show that Bundists were “aware what was happening in Poland and … that the Bund as it was isn’t going to be anymore and they’re really thinking through the implications of it,” he said.

After steeping himself in archival research for his book, Slucki, 34, was moved to write a memoir about his late Bundist grandfather Jakub and father. In 1939, the elder Slucki escaped Wloclawek, Poland, losing most of his family and landing in a gulag-like camp in Siberia. Later emigrating to Melbourne, Jakub became active — along with his son Charles and grandson David — in the Bundist community there, one of three places today where Bund groups remain, along with Paris and London.

In the archives at YIVO, Slucki also found records of his father speaking as a representative of the Melbourne Bund at the Bundists’ 1972 world conference. “In some ways I understood the historical significance of that moment better than he did because I had the archival records and he had only his memory of it.”

From the Bund Archives: Exiles in Siberia, circa 1904. Courtesy of the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Image by Courtesy of YIVO

Pletka, an Australian now living in New York whose great uncle and refugee father were Bundists, participated in Melbourne’s youth movement of the Bund; she said she is inspired to finance the digitization of the Bund’s archive because she personally believes these records represent a valuable chunk of Jewish history that became overshadowed by the Holocaust and events arising from it.

This Bund digitization project is the second major one that YIVO has undertaken. In 2015 the institute began to digitize the prewar holdings of its original collection, which used to be housed at its first headquarters in Vilna but was looted by the Nazis. After World War II, some files were rescued and brought to New York; others remained hidden in Lithuania. YIVO is digitizing these prewar holdings and uniting them online regardless of whether they reside in New York or Lithuania. So far with $5.4 million already raised for the project, the digitization is two-thirds of the way through. Brent estimated that YIVO needs to raise $1 million more to complete that project, with 2022 targeted for its conclusion.

According to Brent, the digitization of the Bund archives will enable some Jews to better understand their great grandparents — not only as laborers but also as people who existed “within a political world in which they could make choices,” he said. “Then you say to yourself, What kind of choices did they make? And that helps you understand something internal to the people not just the external things that are visible.”

Marjorie Backman is a New York-based journalist.