A Case Of Blood Libel In Chicago

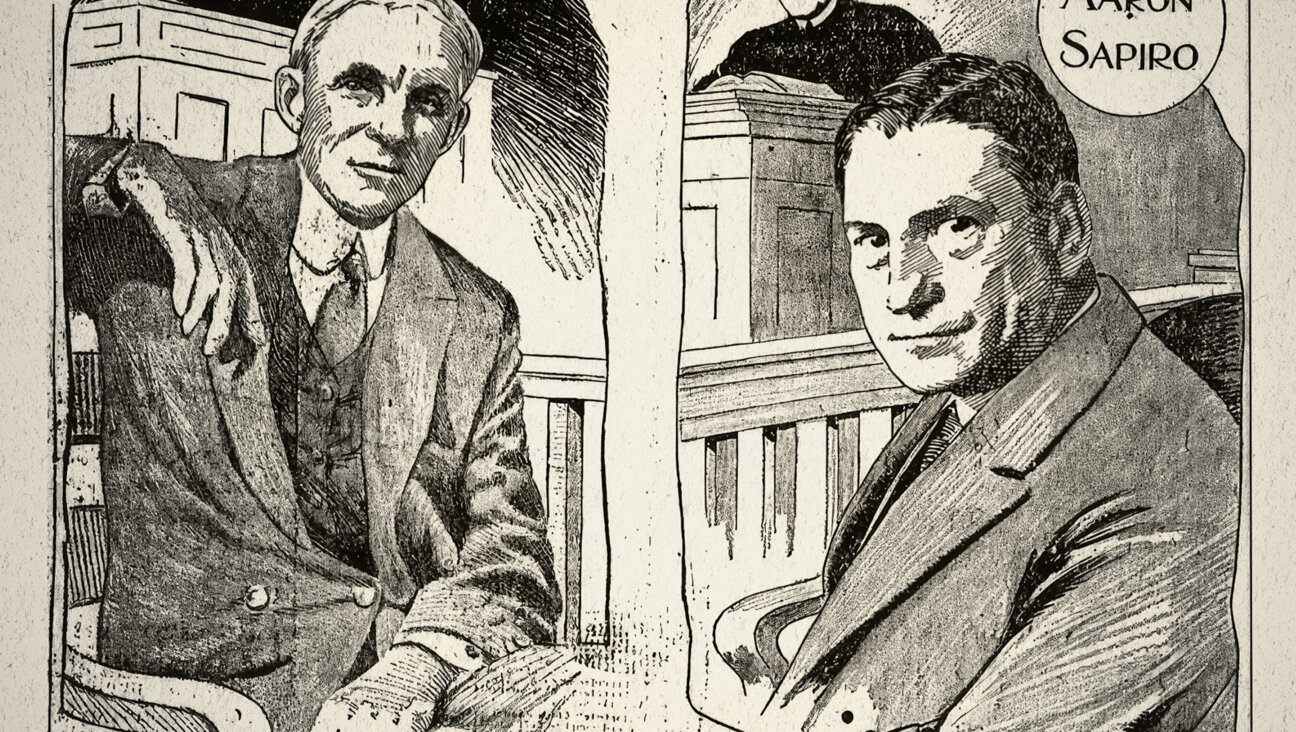

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The accusation against Herris Kahn was a fleeting event in a far corner of Chicago. If not for the reporting in a foreign-language journal and a local newspaper, the story might be completely forgotten by now, a century later. Neither the Tribune nor any of the city’s other six dailies gave it even a sentence. But this local, isolated incident was connected as in a web to momentous events half a world away, events shaped in turn by happenings in Chicago.

For 25 years, Herris Kahn and his sons Moses, Marcus, and Lamos sold dry goods at 8401 South Buffalo Avenue in the Bush, a Polish enclave fast against the Illinois Steel rolling mills in South Chicago. As reported in the Daily Jewish Courier, a militant Yiddish-language newspaper published in Chicago, his troubles began on Independence Day in 1919. Seeing his door open on the nation’s holiday – to admit a repairman, Kahn said – a band of Polish youths pelted the store with mud and stones. Kahn closed the door and left for home.

Within a half hour, a mob of 1,000 assembled on Buffalo Avenue. Their leader, a laborer named Casimir Lota, demanded that Kahn surrender a Polish child locked inside the store. The police arrived, accompanied by Kahn and “several prominent Polish persons.” They searched the store from top to bottom. Finding neither a boy nor anything amiss, the police pronounced the matter closed and ordered the crowd to disperse.

The demonstrations outside Kahn’s store continued the same evening and the next day, the Jewish Sabbath. Lota and his horde still pressed for the boy’s return, now alleging that the Jews had killed him and were planning to use his blood to prepare matzo. The police, they claimed, had found the boy’s body in the store but secreted it out the back.

At the Kahns’ request, their neighbor Frank X. Rydzewski, a member of the county board of election commissioners, asked the Polish clergy to address the matter in their services on Sunday morning. Several of the priests complied. The Chicago police canvassed the community to identify any Polish family missing a son. They found none.

On Sunday, police arrested Casimir Lota, who had “tried to attack” Marcus Kahn, shouting “Return our son!” and “We must kill the Jews!” Prosecutors charged Lota and 17 others with incitement to riot. For the trial later that month before Municipal Court Judge William N. Gemmill, “the courtroom in South Chicago was packed … with Polish men and women,” creating an intimidating atmosphere. Marcus and Lamos Kahn testified, telling of Lota’s “blood accusation … directed against them, and how he had brought the rest of Buffalo Avenue’s Poles to terrorize Jews on the street.” (Herris Kahn was too ill to participate; he died a month later.)

In halting English, Lota testified in his own defense, claiming in fact to have tried to quiet the mob because he knew the Kahns to be “fine people who [were] unjustly accused.” Gemmill had nothing of it. He pronounced all 18 defendants guilty. He rejected the prosecutors’ demand for jail terms but ordered Lota to pay a $100 fine – later reduced to $50 – and the accomplices to pay $10. They discharged their fines, the Courier insinuated, with money given to them by a local Polish druggist.

The tension between Poles and Jews in South Chicago was nothing new. Part of it was the gripes of Polish customers and tenants against Jewish merchants and landlords – and the anxiety of the Polish-American business community that competed with them. Polish business leaders urged Poles to buy from Poles, or as the saying had it, Swój do Swójego (literally, “yours to yours”).

There were also old enmities that had been brought to Chicago from Europe. Discrimination against Jews was common in partitioned Poland, particularly in the areas annexed by the Russian Empire, which included the preponderance of Polish Jews. The oppression intensified after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. For three years, a plague of murder, rape, and pillage fell upon the Jewish community in Russian Poland. The pogroms spurred a mass emigration to the United States and other parts of the Americas. Herris Kahn, his wife Dora, and their three eldest children were immigrants (in 1887) from the Russian Partition in Poland.

The relationship between American Poles and American Jews was particularly fraught right after World War I. By a series of steps commencing in September 1918, a new Polish Republic emerged from the defeat of Germany and the collapse of the Russian and Habsburg Empires. The new Polish state fought wars with Ukrainians in eastern Galicia and with the Soviets all along the border with Russia. By 1920, victorious over the Soviets, it recouped about 60 percent of the territories lost in the Partitions of Poland between 1772 and 1795. For American Poles, it was a time of intense excitement and national pride.

For American Jews, however, 1918 and 1919 was a period of mounting anxiety, alarm and anger. Pogroms swept through the new republic, particularly the contested areas in the east. Between November 1918 and August 1919, anti-Semitic violence hit over 100 Polish cities, towns, and villages. Attackers killed four Jews in Kielce, 64 or more in Lwów (Lviv), 35 in Pińsk, 30 or more in Lida, 65 or more in Wilno (Vilnius), eight in Kolbuszowa, five in Częstochowa, and 31 or more in Mińsk. Many, many more were assaulted, robbed, or terrorized. Polish soldiers played a role in many of the incidents. Most shocking of all was the summary execution of 35 Jewish men in Pińsk accused of plotting a Bolshevik uprising against the Polish army in April 1919.

The atrocities in Poland were widely reported in the American press. The Jewish leadership in America condemned the violence and demanded that Poland take action to end it. The Polish leadership in America, in turn, responded defensively, branding the reports contrived or exaggerated and the brutalities the doing of others or the victims’ own fault, at least in part.

For Poles, more than the national reputation was at stake. The Paris Peace Conference convened in Versailles in January 1919. An independent Poland was the thirteenth of President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points and already endorsed by Britain, France, and Italy. The conditions on Poland’s sovereignty and the extent of its territory, however, still hung in the balance.

The conflict came to a head in May 1919. On the 21st, 150,000 people converged on Madison Square Garden in New York to protest the massacres in Poland and to mourn the dead; 25,000 marched to the Auditorium Theater in Chicago. Addressing the negotiators in Versailles, speakers demanded action from the Polish government and urged that Poland be denied a place in the League of Nations unless and until it guaranteed the rights of its Jewish citizens.

From Chicago, the president of the Polish National Council of America, John F. Smulski, a former West Town alderman and Illinois treasurer, fired off a message to Wilson decrying the “abuse and misrepresentation and attacks on the Polish aspirations for the creation of a united and independent Poland.” Sears, Roebuck president Julius Rosenwald, speaking as a vice president of the American Jewish Congress, and attorney Adolf Kraus, speaking as the president of the Independent Order of B’nai B’rith, both Kenwood residents, cabled Wilson the next day to respond to Smulski’s evasions and omissions. In reply, Nicholas L. Piotrowski, the president of the Polish Roman Catholic Union, headquartered in the Polish Triangle, warned Wilson of the “powerful interests” engaged in intrigues “to deprive Poland of just rights by slandering the good name of the Poles.”

The tone of the leadership was elevated in comparison to Chicago’s foreign-language press. Naród Polski called the Jewish merchants who closed their shops in sympathy with the protest “vermin” and “parasites” and criticized the speakers for failing to mention “the Jewish treacheries in Poland, extortions, bribery, and rascally practices of Jews in business or politics.” According to the Jewish Courier, Dziennik Narodowy ran a cartoon of two men in long coats and yarmulkes nailing Poland to a cross with the caption, “Just as the Jews have crucified Christ, so the Jews wish to crucify Poland.” “Poles in Chicago … are fundamentally no better than those in the Old Country, [despite] the opportunity to learn of … democracy, freedom, tolerance, and justice,” the Jewish Courier raged. They “wish to duplicate here the situation in Poland concerning Jews.”

In May and June, the Jewish press reported attacks on Jewish peddlers in Polish neighborhoods and assaults on Jewish men on the West Side. The Chicago police assigned 250 officers to Douglas Park, reacting to rumors that 5,000 Polish thugs planned to execute a pogrom in Lawndale and an equal number of Jewish toughs intended to prevent it. “I believe the gang fight which has been scheduled … is intended to bring about a final settlement of the dispute between the two factions,” Polish and Jewish, Police Superintendent John J. Garrity said. “Indications point to plans for a desperate struggle.” The 8,000 curiosity-seekers who showed up to see the rumble went away disappointed when the Poles failed to appear.

In June, Polish Prime Minister Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the piano virtuoso, bowed to American pressure and requested the appointment of an American commission to investigate the violence in Poland. Wilson’s commission, chaired by Henry Morgenthau, began its work in July and delivered its report in October. At the insistence of the Western powers, Poland also signed the Polish Minority Treaty, the so-called “Little” Treaty of Versailles, committing the Republic to the “total and complete protection of life and freedom of all people regardless of their birth, nationality, language, race or religion.”

Six days later, out of this roiling mix of resentments and rivalries, Casimir Lota raised his mob at 84th and Buffalo. Even worse was yet to come. Three days after Lota’s trial concluded, on July 29, 1919, Chicago experienced its most searing social conflict, a race riot that began on the lakefront at 29th St.

John Mark Hansen is a professor in political science at the University of Chicago. He is writing a history of the South Side.