A new Holocaust opera premieres — in Thailand

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

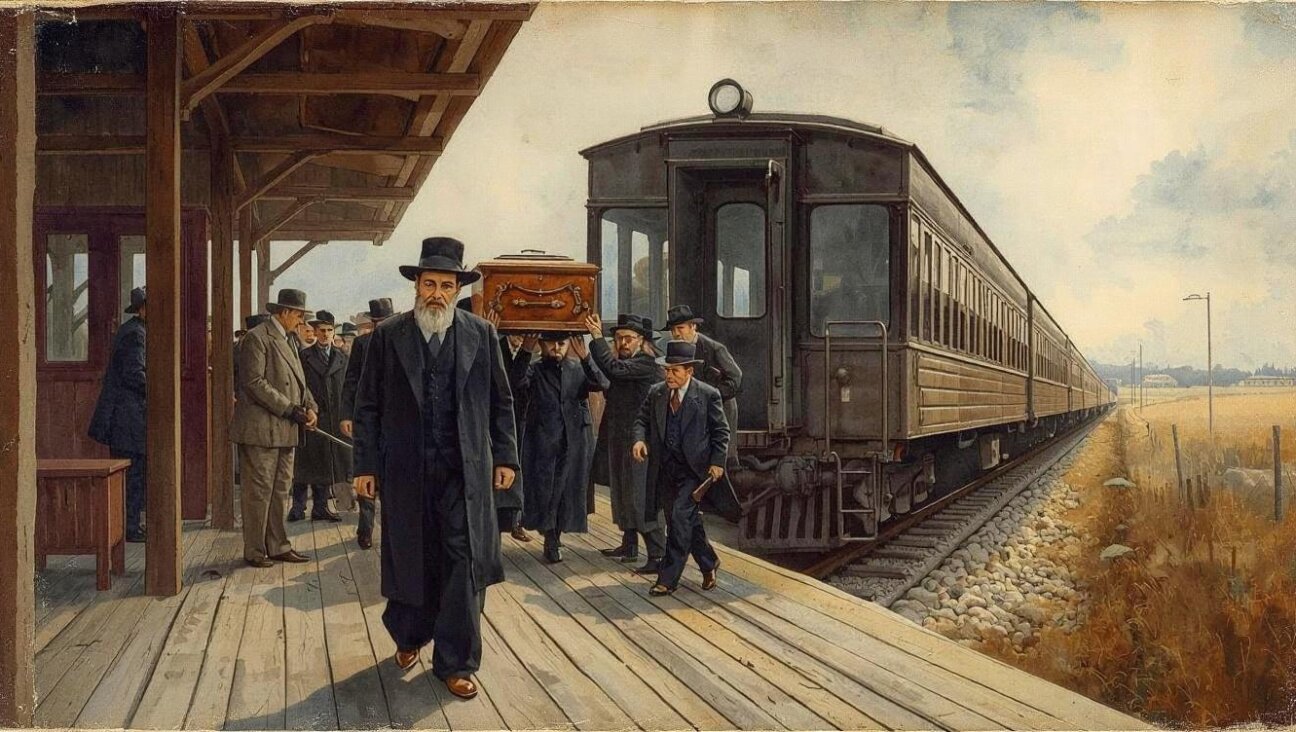

Thailand might not seem the most probable point of origin for a new opera about the Holocaust, but on January 16, the world premiere of “Helena Citrónová” by the composer Somtow Sucharitkul, 67, will be staged in Bangkok.

It is about a real-life Auschwitz survivor of Slovak Jewish origin who at a trial in 1972, testified that a Nazi officer had fallen in love with her and thereafter, saved her and her sister. Despite testimony from others attesting to his crimes, the Nazi was allowed to go free due to a statute of limitations.

Citrónová’s story gained further currency in a 2005 BBC-TV documentary, “Auschwitz: The Nazis and the ‘Final Solution’” in which she was interviewed.

It inspired a controversial romance novel about a Jewish prisoner at a Nazi concentration camp whose love for a Nazi commandant redeems him. As The Forward reported in August 2015, this book sparked objections, notably from Katherine Locke, a Jewish writer based in Philadelphia.

Far from Auschwitz and Philadelphia, Somtow Sucharitkul, who writes and composes under the name S.P. Somtow, published his libretto for Helena Citrónová in 2018.

A polymath, Somtow is a conductor as well as composer, having founded orchestral ensembles, including one that performed a complete cycle of Mahler symphonies, and an opera company in the Land of Smiles.

Somtow is also a science fiction and horror author; Isaac Asimov, of Russian Jewish origin, ranked him among the “excellent new writers” of science fiction, while Robert Bloch, author of “Psycho” (1959), termed Somtow a “brilliant and important new writer whose work is like a bolt of lightning – it is both illuminating and electrifying.”

Shortly before the premiere of his Holocaust-themed opera, Somtow took time to share his motivations with The Forward’s Benjamin Ivry.

Somtow Sucharitkul Image by Courtesy of Opera Siam

Last October, you tweeted a response to those who wonder why you chose the subject of Helena Citrónová by citing lines from Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem “Babi Yar,” about Nazi atrocities in the USSR: “Today, I am as old/ As the entire Jewish race itself,” adding “This story belongs to all of us.” What did you mean by that?

Somtow Sucharitkul: People ask me all the time why should I talk about these things as if I were somehow schnorring in on someone else’s life. I was born in Thailand, but left when I was six months old and lived in Europe for most of my childhood, so it feels like more of my past than what happened in Asian countries. The reason I started getting involved in Jewish issues in Thailand were that none of my students here knew whether Thailand had won or lost the Second World War. I was in the Terminal 21 Shopping Mall [in Bangkok] and saw a statue of Hitler dressed as Ronald McDonald. No one meant anything by it, but it was a terrible moment of disjunction, and I felt that I should explain to young people around me and those in a wider range.

You posted on Facebook in October that in the opera’s final scene, when you set the heroine’s words, “My father told me once, never forget you’re a Jew,” you chose to rework a melody from Wagner’s “Die Walküre.” You add that this was done “unconsciously,” but using the notorious anti-Semite Wagner’s music in this context was an “allusion so cogent and so trenchant that my unconscious must have intended it.” So was it intentional or unconscious?

I imagine it was unconsciously intentional. At the time I wrote those notes, I thought to myself, this is Wagner, but I couldn’t place it. That was an odd moment, I have to admit.

When you programmed in Bangkok Hans Krása’s opera “Brundibár,” first performed in 1943 by children at Theresienstadt concentration camp (Terezín), and the Russian Jewish composer Grigori Frid’s “Diary of Anne Frank” (1968) as well as Michael Tippett’s oratorio “A Child of Our Time” inspired by the events surrounding Kristallnacht in 1938, what were your goals?

I wanted to help the Israeli embassy to commemorate Holocaust Memorial Day in January. Because it is about humanity. This is also about that such things should not happen again. I sometimes tell people that the past is like a mirror and we don’t dare look into it because we are afraid of seeing ourselves.

Your novel “The Other City of Angels” (2008) is set in Bangkok, where Judith Abramovitz, an American socialite, marries a Thai man who may be a serial killer. Judith experiments with Thai animism and other mysticism. Do you know any American Jewish expats who try Thai popular religious beliefs?

She’s like so many of my friends in the States, but not like many of my friends in Thailand. When I lived in the States, I lived in the East Coast and Los Angeles in a culturally Jewish milieu, so I was fascinated by how these friends might react when they were in Thailand.

The literary critic David Punter has compared Judith Abramovitz’s story to that of the “Wandering Jew who seeks forbidden knowledge.”

Oh my God. (laughs) That’s certainly reading a lot into it. I never thought of it like that, but it’s sort of cool. But the Wandering Jew myth is that he is punished for some anti-Christian thing, and that was the farthest thing from my mind.

In another novel, “Aquila in the New World” (1983) set in another dimension where ancient Rome never fell, adventurers meet a certain Abraham bar-David and a group of Jews who remain loyal to their customs, admitting to an “irresistible appetite for this smoked salmon, which we devour constantly with a kind of round, holed bread loaf smeared with creamed cheese.” So bagels and lox will survive into other dimensions and worlds?

Well, I have tried to find good [bagels and lox] in Bangkok without much success. My editor at Del Rey Books in New York was very Orthodox and once she met me for lunch on Saturday on the top story of my hotel. She walked up all 22 flights because it was Saturday. Her faith was so central to her existence that she did this without thinking. This drew me greatly into looking more closely at my Jewish friends and started a lifelong interest that led to writing this opera.

In 1987, you told the Los Angeles Times, “I had initially envisioned myself becoming the Kwisatz Haderach, the term for a future-day messiah used in the science fiction novel “Dune” of Thai music.” Kfitzat ha derech is in fact an equivalent of the term shortcut, but what is the appeal of Hebrew language to science fiction authors such as yourself or Frank Herbert, author of “Dune”?

That’s a very interesting question. One of the most intriguing ideas about the Hebrew language is that words contain their own essences, that words are by their nature magical, in some sense. I don’t know what language is the ur-language of the universe, but Hebrew has the sound that it might be, it has that kind of ring to it.