Louise Glück, Jewish poet of classical themes, wins the Nobel Prize

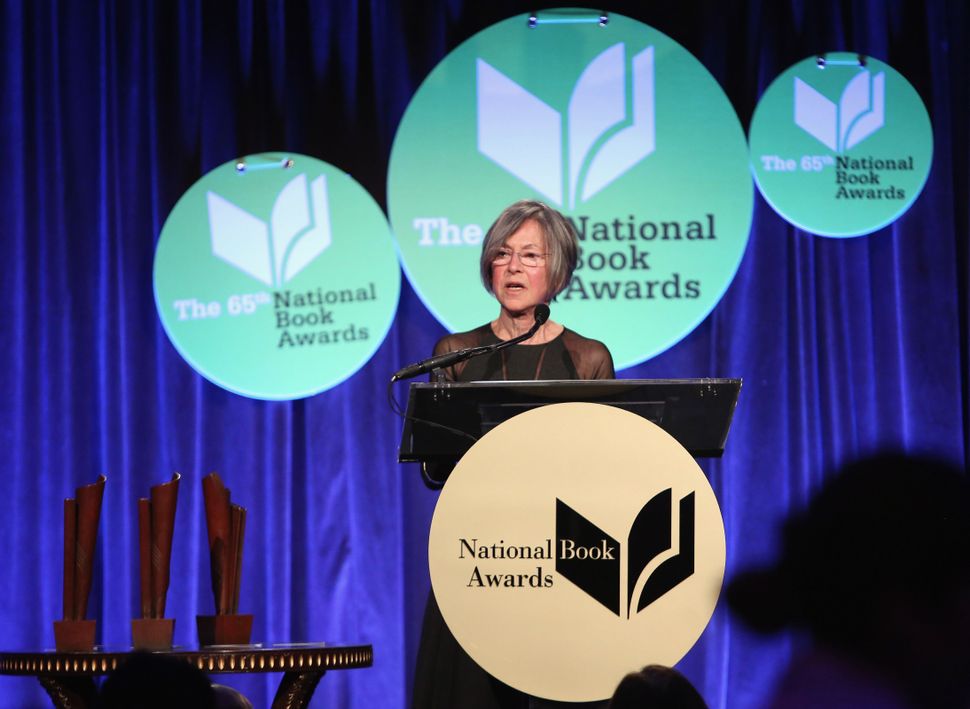

Image by Robin Marchant/Getty Images

In the maelstrom of coronavirus, Borough Park protests and vice-presidential debates, finally some good news: Poet Louise Glück has been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. The granddaughter of Hungarian Jews who ran a New York grocery, she is the first Jewish literature laureate since Bob Dylan, who took the prize in 2016. The Swedish Academy praised the 77-year-old poet, citing “her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

The author of such collections as “The Triumph of Achilles,” “Meadowlands,” “Vita Nova,”“The Seven Ages” and the book-length poem “October,” responding tp the September 11 attacks on her native New York, Glück has collected numerous accolades throughout her career including the Pulitzer Prize, the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for Nonfiction, the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle award and a Guggenheim fellowship. Her most recent collection is 2014’s “Faithful and Virtuous Night.” Between 2003-2004, she served as the U.S. poet laureate, and she has taught at Williams College and is currently on the faculty at Yale.

In a phone call with a representative of the Nobel Prize following the announcement, Glück, in her custom erudite yet self-effacing style, started off with a relatable assertion: She could only talk for two minutes, she said, because “I really have to have some coffee or something right now.” Asked how the Nobel might change her life, she responded “My first thought was, I won’t have any friends, because most of my friends are writers. Then I thought, No that won’t happen. It’s too new, you know. I don’t know really what it means.” And, later, “I thought, well I can buy a house. But mostly I’m concerned for the preservation of daily life with people I love.”

Writing in The New York Times about her collection of poems written between 1962-2012, critic Dwight Garner praised her early work as having “a great novel’s cohesiveness and raking moral intensity. They display a supple and prosecutorial mind interrogating not merely her own life but also the sensual and political nature of the world that spins around it.”

In the same review, Garner mentioned how apt it was, given her incisive verse, that her late father helped invent the X-Acto knife.

When Glück’s father passed, she wrote the collection “Ararat” as a response. Named for the mountain region where Noah’s settled his Ark after the flood, it is one of many instances where her work, so steeped in mythology, drew references from the Hebrew Bible as well. Her work has been highlighted in The Forward on numerous occasions.

While some might ascribe Glück’s first response to winning the prize to shock, it’s in fact characteristic. In a 2009 interview with “American Poet,” Glück said, “When I’m told I have a large readership, I think, ‘Oh great, I’m going to turn out to be Longfellow’: somebody easy to understand, easy to like, the kind of diluted experience available to many. And I don’t want to be Longfellow. Sorry, Henry, but I don’t. To the degree that I apprehend acclaim, I think, ‘Ah, it’s a flaw in the work.’”