Are virtual minyans and avatar rabbis the future of Judaism?

Some Reform and Orthodox Jews are finding a place to practice their religion in the Metaverse. Could a virtual Passover celebration be far off?

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

This past Hanukkah, Rabbi Steven Stark Lowenstein didn’t give Kiddush cups or gift cards to his staff at Am Shalom, a Reform congregation in the Chicago suburb of Glencoe. Instead, the cantors, rabbis, educators and administrators who make up his staff of 18 received Oculus virtual reality headsets.

“It was great fun,” Lowenstein wrote me in an email, “and sent a message that VR is real.”

In October, Lowenstein set out to make Am Shalom “the first Jewish synagogue in the metaverse,” referring to the emerging network of 3D virtual worlds whose name was coined in “Snow Crash,” a 1992 sci-fi novel by Neal Stephenson.

Big Plans: Am Shalom’s goal is to open a 3D digital synagogue by Passover, so anyone with an online avatar can have an immersive experience. Courtesy of Am Shalom

The senior rabbi, who is near 60, enlisted the help of younger tech-savvy congregation members and kept his efforts relatively quiet, careful not to dip into the congregation’s budget. He knew he’d raise eyebrows when, in mid-November, he spent $10,000 worth of cryptocurrency on a land parcel on the Island of Scarcity in the virtual world of Cryptovoxel.

So far, Lowenstein has only streamed a temple concert in an NFT art gallery, but his goal is to open a 3D digital synagogue by Passover, so anyone with an online avatar can have an immersive experience. He plans to host virtual events with Jewish-themed NFT giveaways and livestream Shabbat services.

But there’s competition.

In Decentraland, a parallel virtual world, Chabad Lubavitch, the Brooklyn-headquartered Hasidic movement, is constructing a center. Without knowledge of Lowenstein’s plans, they announced in January that they will be “the first Jewish presence in the metaverse.”

For now, digital saw horses mark off the center’s future location between an NFT art gallery and a kiosk labeled “Beauty Land,” which plays a German-based bitcoin firm’s promotional video in Turkish, Greek and Spanish, all subtitled in Chinese. Chabad purchased the virtual plot for 6,000 MANA, the blockchain currency which powers Decentraland, worth over $14,000 today.

The project is spearheaded by Rabbi Yisroel Wilhelm, head of the Rohr Chabad Center at University of Colorado; Rabbi Shmuli Nachlas, director of the Jewish Youth Network of Ontario; and tech expert Alex Gelbert. According to Wilhelm, the rabbis decided to go ahead with the project during Passover 2021, naming it The MANA Chabad Jewish Center, aptly referencing the Book of Exodus and the cryptocurrency.

While they have no opening date set, their website has images of the future virtual center. The exterior is a digital replica of the Hasidic court’s red-bricked Eastern Parkway headquarters. Inside is a large open space with high ceilings and a photo of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the movement’s spiritual leader who died in 1994.

Wilhelm says the center will be staffed and will function like the Chabad Houses found on college campuses and in over 100 countries worldwide that aim to meet the spiritual and material needs of Jews. The difference being that a “mensch avatar” will be the one asking “Are you Jewish?”

Since it’s Orthodox, the online center will operate at most 24/6.

“We’re not going to be doing anything on Shabbat or holidays,” said Wilhelm.

Both Rabbi Wilhelm and Rabbi Lowenstein boast that their decisions to enter the metaverse came before Mark Zuckerberg renamed Facebook as Meta at the end of October. The tech giant made its announcement in an 80-minute presentation highlighting the potential of the technology. In it, a cartoon Zuckerberg hopped between highly realistic fantasy worlds as he interacted with co-workers and friends.

The video and brand change drew mockery, in part because Meta means “dead” in Hebrew. But it was also a turning point for the virtual worlds. Metaverse became a buzz word, and the rebranding signaled that Zuckerberg was betting billions that immersive experiences, not social media, would be the foundation of our future online lives.

The potential for virtual worship is already apparent. Even though the metaverse is often called “soulless,” other religions do have a presence. I visited a detailed virtual mosque that attracts passing avatars with the rhythmic chanting of the Quran. It sits next to a towering standing Buddha statue.

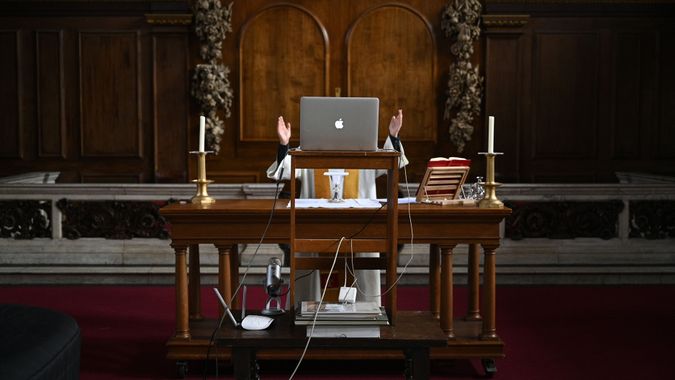

Church in the Metaverse: The reverend Lucy Winkett, rector of St James’s Piccadilly, delivers a service on Rogation Sunday via webcam to the church’s congregation. By Getty Images

For Christians, there are places like VR Church, which controversially has baptized followers in virtual water. And, according to The Associated Press, the app EvolVR lets users meditate “in a virtual incarnation of a Tibetan Buddhist temple high in the mountains or floating weightlessly looking down at the Earth.”

However, neither Lowenstein nor Wilhelm is certain about how Judaism will look in the metaverse.

“We haven’t even figured out how to put a yarmulke on an avatar,” said Wilhelm. Which is fair, no one really knows how the metaverse itself will work. According to Zuckerberg, it doesn’t even fully exist yet.

Both Wilhelm and Lowenstein see their virtual projects as ways to reach a younger generation that is increasingly disengaged with religion.

How Zoom Shabbat May Become Metaverse Shabbat

The Future of Religion? In the synagogues of the Metaverse, worshippers will don headsets to join immersive virtual experiences where rabbis and congregants form cyber-minyans untethered to a physical synagogue. Image by Chabad

Back in October, Lowenstein had never heard of the metaverse when a congregant, who is a hedge fund manager, challenged the Reform rabbi to create a digital synagogue, promising a crypto donation to fund it.

The rabbi had always been an early adopter of tech in the temple. Eight years earlier, he had started streaming Shabbat and holiday services. What was then seen as a novelty or even fringe, became commonplace for Reform and Conservative congregations during the pandemic.

Am Shalom’s Zoom bnai mitzvahs, quarantine shivas and Facebook Live prayer services won the attention of the Chicago Sun Times, which featured the synagogue in a May 2020 article about keeping communities socially distanced but spiritually close.

The metaverse is the logical next step. Bill Gates says that within two or three years, office Zoom meetings will move into 3D virtual spaces, using technology that replicates the real feel of interacting in a physical space.

Rabbi Lowenstein believes the same will eventually happen with Zoom-like 2D Shabbat service broadcasts. Worshippers will don headsets to join immersive virtual experiences where rabbis and congregants form cyber-minyans untethered to a physical synagogue.

“If my kids can play 18 holes of golf in my living room while using their Oculus with another friend from New York playing the same course, why can’t we do the same thing with learning a Torah portion or experiencing a Jewish holiday?” Lowenstein asked in a phone interview.

Virtual shul isn’t the rabbi’s first preference for engaging young Jews, but he’s a realist.

“As much as I hope that they will come to sit in my building, and experience what we’re doing, I want to find ways to come to them and to bring those same high-level experiences,” he said. “And if it means streaming it onto the metaverse, I’m willing to try that.”

For the Reform rabbi, this doesn’t mean compromising his beliefs. “Our function is to take the old and make it new, and take the new and make it holy,” he said paraphrasing Rav Kook, the first Chief Ashkenazi Rabbi of pre-state Israel. “The metaverse is something new that we have to find ways to make holy.”

Bringing Avatar Jews Back Down to Earth

First Synagogue in the Metaverse? Am Shalom, a Reform congregation in the Chicago suburb of Glencoe, is on the forefront of innovation. Courtesy of Am Shalom

While the Reform movement adapts Judaism to the modern world, Chabad adapts the modern world to Judaism.

Chabad has long embraced technology as a means to spread their traditional beliefs. Chabad.org launched back in 1993, making it one of the first 500 websites on the internet.

Before the pandemic, cryptocurrency and NFT-enthusiast students at the University of Colorado brought up the idea of a Chabad house in the metaverse to Rabbi Wilhelm.

“They look at it as something very pure and good, they think that people are creating a positive change in the way we look at currencies and other things,” said Wilhelm.

Wilhelm doesn’t share the idealist view that blockchain will remake the world by decentralizing power and data, but he and Nachlas see the metaverse as a place to reach “unreachable Jews.”

Chabad describes their future center in Decentraland as something similar to their outposts in far-flung places like Dharmesala, India, or at the foot of Macchu Picchu.

“Wherever there are Jewish people, there are Chabad-Lubavitch emissaries working to teach, guide and uplift them,” states an article on Chabad.org. “Even when they are avatars.”

But it won’t be possible to offer a Jewish traveler a kosher meal in a virtual center, or offer shelter and material assistance like the movement has done in recent days in Ukraine. Nor can you pull an avatar into an actual sukkah or mitzvah tank.

While Wilhelm mentioned potential educational activities and festivities like a Purim celebration and a menorah lighting in a public square in Decentraland, Chabad warns that an expanding virtual world may lead Jews to “shrink their physical reality, the one that truly counts.”

In the comments section of a January Chabad.org article about the new center, some followers questioned the wisdom of any engagement in the metaverse. Calling it a “grave danger,” one commenter asked whether it would be appropriate for a nonmarried man and woman to meet alone in the metaverse or touch virtually.

“I’m not here to control the negative things that are happening in the metaverse. That’s not my job,” said Wilhelm. Chabad’s goal, he added, is to meet Jews wherever they may be spiritually and then, as their website puts it, to “bring users ‘down to earth’ for Shabbat dinners, tefillin, shaking the lulav and etrog, and all other mitzvot that can only be done in the flesh.”

Still, Wilhelm sees great potential, looking at the success of Chabad on the internet. “We were the first,” Said Wilhelm, “and now we’re the biggest.” The movement’s tech savviness and dedication to outreach has given them an outsized voice in all things Jewish.

“It’s very powerful,” said Andrea Lieber, a Judaic Studies professor at Dickinson College who studies religion and technology. “Google almost anything Jewish, the first hit you get is almost always Chabad.”

Judaism 2.0

A Familiar Place: The exterior of the virtual Chabad center is a replica of the movement’s headquarters on 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn. Courtesy of chabad

If the metaverse is “the next chapter of the internet,” as Mark Zuckerberg claims, then being the first Jewish group in the metaverse brings more than just bragging rights. It could mean defining Jewish-ness in the future.

Over time, the technology will improve and become more mainstream. Eventually, there may be an app for Jews to pray at a hyper-realistic digital Western Wall, or cyber sukkahs in the metaverse under renderings of the Milky Way. Hebrew school lessons could make the book of Isaiah come alive through a VR simulation.

Orthodox Jews, who make up 10 percent of American Jews, may not accept cyber minyans, but there are plenty of opportunities for them to gather and practice Judaism in the metaverse.

Lieber, who has studied the web streaming of Shabbat services, believes advances in technology allow Jews to experience a wider variety and more personalized spiritual experiences. But she says the ability to stay at home and take religious classes or attend a service from far away synagogues, comes at a cost of eroding the local synagogue as a place where Jewish communities come together.

What is permitted in terms of technology, she says, changes over time. Often those changes are the result of prioritizing values like inclusivity or compassion. For example, Orthodox rabbis permit hospitalized followers to use the phone to meet their religious obligation to hear prayers like the Havdalah.

And it may not be the religious authorities who get to decide how Judaism is practiced in virtual reality. Sometimes, she says, religious law “lags behind what people are doing.”

By the time the Conservative movement leaders in the 1950s laid out rules for driving to synagogue on the Sabbath, Lieber said, members had long been carpooling to shul. Even in the Orthodox community, concessions to technology have been made, like Shabbos elevators and changes to cooking practices on the day of rest.

Virtual reality may seem like a big leap forward, but greater portions of our days, and more aspects of our lives have migrated to the internet. Apple Watches, Peloton bikes and Alexa have blurred the lines between our physical and digital worlds. And more and more people are creating avatars, socializing and spending real money in the metaverse or in video games like Fortnite.

Eventually, some predict we will live part-time in the metaverse, working, shopping, exercising and, depending on who you ask, even praying.

That moment may come sooner than you expect.

“Passover is going from the narrow spaces to the open spaces,” said Lowenstein who is putting the final touches on his virtual synagogue. “It would be a perfect time to be visible in the metaverse.”