How the war already changed the meaning of one artist’s childhood — and her painting

‘When they started bombing Kyiv, there was no place left for fantasy,’ painter Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi said

The war in Ukraine changed Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi’s work, and her life. Graphic by Matthew Litman. Artwork by Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi

The first thing Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi drew after Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine was a little girl in pigtails looking through a window. When you look at it, pops of red catch your eye: The girl’s black-and-red checkered skirt. The bright red jacket of a man in the street, his arms outstretched in the face of a menacing black tank. Smudges of yellow and mostly red fire spilling out of the building across the street, bathing the scene in an eerie pink glow. Next to the artist’s signature is a tiny Ukrainian flag.

Girl at a Window: In Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi’s painting, a girl in pigtails watches as Russian forces lay siege to her neighborhood. By Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi

Some elements of this scene might feel familiar to fans and followers of the Kyiv-born, Israel-based artist. In “Mama” (2016), a little girl also looks through a window, waiting for her mother to come home at the end of the day. But in that instance, the reds and pinks paint a cozier picture: Red polka dots on the girl’s white shirt. A vase of flowers perched on the TV. And more florals — red in the rug and pink on the wallpaper. Outside is calm, tinted a frosty blue, snow falling as a lone figure in black raises an arm in a friendly wave.

When she saw the first photos of bombings and Russian tanks entering Ukraine, “I was really feeling like they’re coming into my childhood landscapes and ruining them,” said Cherkassky-Nnadi, who grew up in Kyiv before immigrating to Israel at age 14 in 1991, right before the collapse of the Soviet Union. “These landscapes, they belong to peaceful times,” she said. “All these neighborhoods, they don’t belong to war stories.”

‘The Country I Grew Up in Doesn’t Exist Anymore’

For years, Cherkassky-Nnadi has documented scenes plucked from her memories of Kyiv as part of her “Soviet Childhood” project. She began working on it when she was pregnant with her daughter — who’s now six. She thought about her daughter’s future childhood and recalled her own in the bygone Soviet era. “This country that I grew up in doesn’t exist anymore,” said Cherkassky-Nnadi, speaking to me on Zoom from her studio in Israel.

She started with a few drawings, and those stirred her memory. Visuals flashed in her mind — like getting ready for school on a cold, dark morning that still feels like night, or a grandmother coming home laden with bags as the children rush over to see what she brought them. “It became a very big project because these memories, they just come and come. They are still coming.”

Cherkassky-Nnadi’s 2019 “Soviet Childhood” exhibition with the Fort Gansevoort New York gallery marked her U.S. solo debut. New York Times critic Roberta Smith lauded the show as a “knockout,” deeming it “merely the tip of a very engaging iceberg.”

“Her wise, appealing works are alive with color, detail and, often, humor,” Smith wrote. “But they are also psychologically subtle and socially astute.” Adam Shopkorn, co-founder of Fort Gansevoort, remembers visitors who’d grown up in the Soviet Union basically showing him and his colleagues around — giving tours in reverse — “so they could explain what their childhood was like and what we were looking at,” he said. “It really struck a chord.”

It was this project and another — “Pravda,” which plumbed the experiences of Soviet immigrants to Israel and was shown at the Israel Museum in 2018 — that spurred Cherkassky-Nnadi to begin traveling regularly to Kyiv again. When she’d first arrived in Israel as a teenager, there was no internet and calling was too expensive, so she and her friends wrote letters to each other to stay connected. She spent a month back in Kyiv after graduating from high school in 1996, but she didn’t go back until 18 years later when her art pushed her to return again and again.

“I needed the landscapes, because I’ve noticed that every time I tried to depict Kyiv, it comes out Berlin, because I was living in Berlin, and it’s similar in a way, but it’s not the same,” said Cherkassky-Nnadi, who lived in Germany from 2005 to 2009. “I go there to hunt for my childhood landscapes, always collecting.”

Most recently, she traveled to Kyiv this past fall with her daughter and the filmmaker Anat Schwartz, who was working on a 30-minute documentary about the artist as part of her “Muses” series.

“Usually, I just see what I see,” Cherkassky-Nnadi said. But filmmaker in tow, they made an effort to go into her old school, for example, where a couple of the classrooms looked exactly as she remembered them. “It was like, you open the door and there’s a time machine,” she said. “I experienced it several times during this trip, and I think this was the deepest travel into the time that I had in Kyiv. And it was so symbolic that it happened just four months before the war.”

‘When They Started Bombing, There Was No Place Left For Fantasy’

If you’d asked her before Feb. 24, Cherkassky-Nnadi would’ve told you a war like this wouldn’t happen.

“I told everybody I don’t believe that Russian tanks will actually enter Kyiv,” she said. “But when they started bombing Kyiv, there was no place left for fantasy.” Russia had invaded the city of her childhood and she recognized the streets and neighborhoods they were attacking. “Every day I’m looking, I think, what will be left from these places?”

Her primary focus in the early days was helping her family get out. When the bombing started, her sister and her sister’s daughters and two small grandchildren left Kyiv for a nearby village. “They thought they will wait a little bit and then it will finish and then they will come back,” Cherkassky-Nnadi said, until they realized “it’s not going to finish and it was getting more and more scary.” That’s when they decided to see if they could make their way to Israel.

In the days that followed, Cherkassky-Nnadi was constantly on the phone as she tried, like so many other Soviet immigrants around her, to stage what she called a mivtzah hilutz, a rescue operation, from afar. There were “no flights and no road — like the road has been bombed and you don’t know which road is open,” she said. After a “nightmarish week of their escape,” as Cherkassky-Nnadi described it in one of the many Facebook and Instagram updates she’s posted in response to the war, they finally landed at Ben Gurion Airport March 4. And for the first time since the ordeal began, she felt like she could breathe.

In a comment on one of her posts a few days later, someone asked where she was located. “My body is in Israel, but I’m in Ukraine,” she replied.

“I was so much inside of it that even when I went out on the street, I was thinking, like, ‘Is it safe to go on the street now?’” she told me. “And then I thought, like, ‘I’m in Israel, nothing is going on on the street now.’”

That Was Then, This Is Now

The war was only a few days old when Cherkassky-Nnadi posted her rendering of the little girl at the window. She offered to sell it in exchange for a donation to Ukraine (It went for about $1,200, she said, and the buyer chose to support the Ukrainian army).

Over the last several weeks, she’s continued to draw and paint. “This is just what I always do, you know, in difficult times, in easy times, in whatever times, this is what I do,” she said. “Some of the news that I was receiving triggered my memory,” she said, adding that those memories evoked drawings she’d made before. She kept thinking about how “the war has changed this subject and has changed this landscape.”

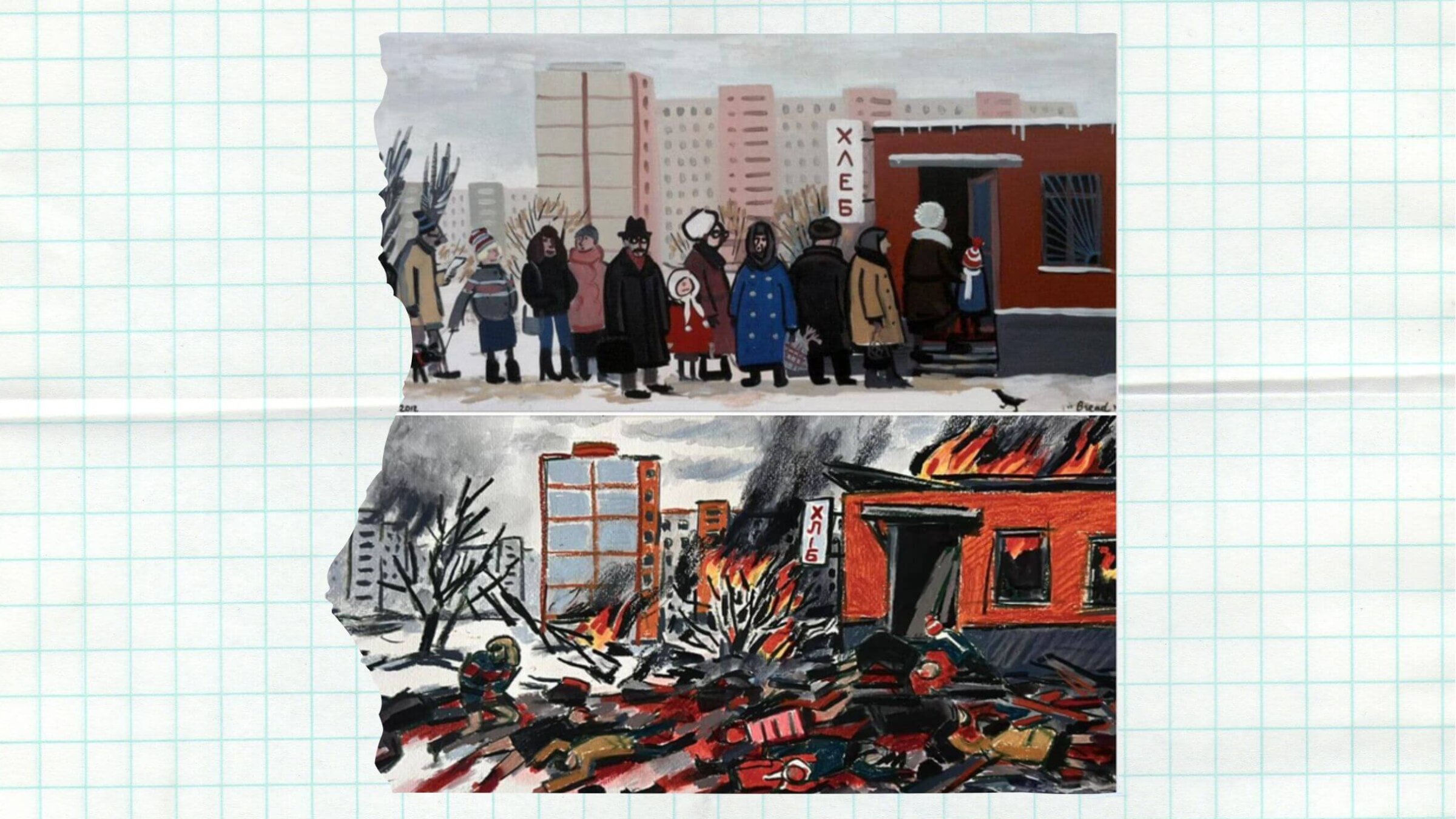

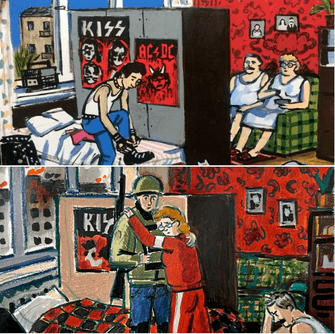

So she started pairing existing drawings from her “Soviet Childhood” project with new ones, depicting striking contrasts of before and after:

Before, a woman stands with her son on the balcony on a pleasant day, gazing out at a street lined with golden trees under a pale blue sky and tufts of sun-kissed clouds. After, the mother and son clutch each other, watching from the same spot as tanks roll down the thoroughfare and everything around them burns black and red.

Before, people form a neat line as they wait for bread, bundled up against the cold. After, Russian forces have fired on these civilians — as they did in Chernihiv — leaving behind a pile of bodies leaking blood onto the snow.

Before, a teenaged son decked out in punk collar, belt and gloves, laces up his boots alongside his KISS and AC/DC posters as his parents sit on a couch on the other side of a room divider in their small apartment. After, that son dons an army green jacket and helmet, rifle slung over his shoulder, as his mother hugs him and his father clutches his hair.

An Act of Solidarity With Ukrainians

As various pockets of the art world have organized exhibitions and fundraisers, Cherkassky-Nnadi has been quick to support them. She participated, for example, in Withdraw the War, an exhibit and art sale that ran in Tel Aviv in early March and continued online. For this event, Cherkassky-Nnadi donated the existing painting “David’s eye,” depicting a scene from her old art school in Ukraine. She’d heard from ex-classmates that the neighborhood, and perhaps the school itself, had been bombed. It sold for 5,500 NIS (about $1,700) to a man whose grandmother was born in Mariupol.

“Some of the visitors came to the exhibition just to see her work,” Mariia Malakh, one of the Withdraw the War organizers, said in an Instagram message. “Some of them asked straight at the entrance where can they see Zoya’s painting?” Including Cherkassky-Nnadi, who Malakh emphasized is one of the most famous Ukrainian-born artists in Israel, was important to the organizers, “as her voice and support will give more attention to war in Ukraine.” And ultimately, the event “wasn’t just about selling art — it was an act of solidarity with Ukrainians.”

Cherkassky-Nnadi is also partnering with Fort Gansevoort to sell 100 prints of her drawing of the woman and child standing on the balcony watching the tanks roll by, with half the proceeds going to the Ukrainian Red Cross via the International Committee of the Red Cross. Barely a week after the announcement, Shopkorn said, about a quarter of the prints had already sold at $1,000 a piece.

The artist donated another existing painting, of a Georgian children’s band in the 1970s, to Art Aid Israel Ukraine, a sale that’s intended to support residencies for Ukrainian artists in Israel. “When we talked to her about it, she stressed that at the moment the most important thing for her is to participate in any exhibition that will make a contribution to Ukraine,” Svetlana Reingold, one of the curators, said in an email in Hebrew.

“With each additional moment of this terrible war, more and more pieces of life she knew are collapsing before her eyes,” Reingold added. And as Cherkassky-Nnadi creates these diptychs of before and after, “her paintings become testimonies of the atrocities taking place at this time in her homeland.”

‘I Don’t Know How Big It Will Get’

It was a Sunday afternoon one month into the war when Cherkassky-Nnadi and I spoke on Zoom, and she was drawing even as we spoke. I could hear pencil scratching paper and noticed her eyes fluttering up and down. When I asked her about it, she held up the work-in-progress for me to see.

It was still outlines, mostly, but I could begin to make out the crowded train she described. The before that had flashed in her memory was her 2015 drawing “To the South” — a vibrant snapshot depicting a group of women and children on a train, munching on a meal as they head south for vacation. The after is a bleaker scene in a similar train car, inspired by a cousin’s recent journey as she fled to western Ukraine in a train packed to the brim.

Cherkassky-Nnadi said she didn’t have any concrete plans for the series quite yet. “I don’t know how big it will get,” she said. “I hope not very big.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO