Lego rabbis, Hasidic coloring books: How toy makers and publishers created an alternative Jewish universe

A new book explores the toys, music and kids’ books found in strictly Orthodox homes.

A “Shabbos Table” set from Kids Play depicts a typical haredi Orthodox family at home. The designer, Shlomi Eiger, says the brand is part of a “contemporary trend of Haredi children’s toys and games designed from within the community.” (Omar Friedman)

(JTA) — I grew up on “Encyclopedia Brown,” a series of books about a grade-school Sherlock Holmes who solves one-minute mysteries. You know the type: “If you didn’t steal the bicycle, how did you know it was blue?”

Encyclopedia’s world looked just like mine: white, suburban, middle-class. If he had a religion, it wasn’t obvious – which, except when we peeled off on the major holidays or for Sunday school, was also true of me and my friends. I later joked that there should be an all-Jewish version of the books, in which the hero solves highly specific Jewish mysteries. I even proposed a name: “Encyclopedia Judaica Brown.”

It turns out, there is such a thing: “Gemarakup” (roughly, “Talmudic brain”) is a children’s book series created for the haredi, or fervently Orthodox, market. Its hero, according to Volume 2, loves “solving mysteries, almost as much as he love[s] studying Torah” (note that “almost”).

I learned about “Gemarakup” in “Artifacts of Orthodox Childhoods” (Ben Yehuda Press), a new collection of essays edited by Dainy Bernstein, who teaches children’s and young adult literature, among other things, at CUNY’s Lehman College. Written by scholars and writers who grew up immersed in books, toys and songs created for the religious Jewish market, it is an introduction to a world that a non-Orthodox Jew like me may only have glimpsed through the window of a Borough Park Judaica store.

Its titular artifacts are an alternative universe of pop culture: Lego-like sets featuring tiny rabbis in their studies and modestly dressed moms making challah; children’s songs that rework secular genres to teach sexual restraint and the power of prayer; a coloring book in which even Adam and Eve are fully dressed in the clothing of Hasidic Jews.

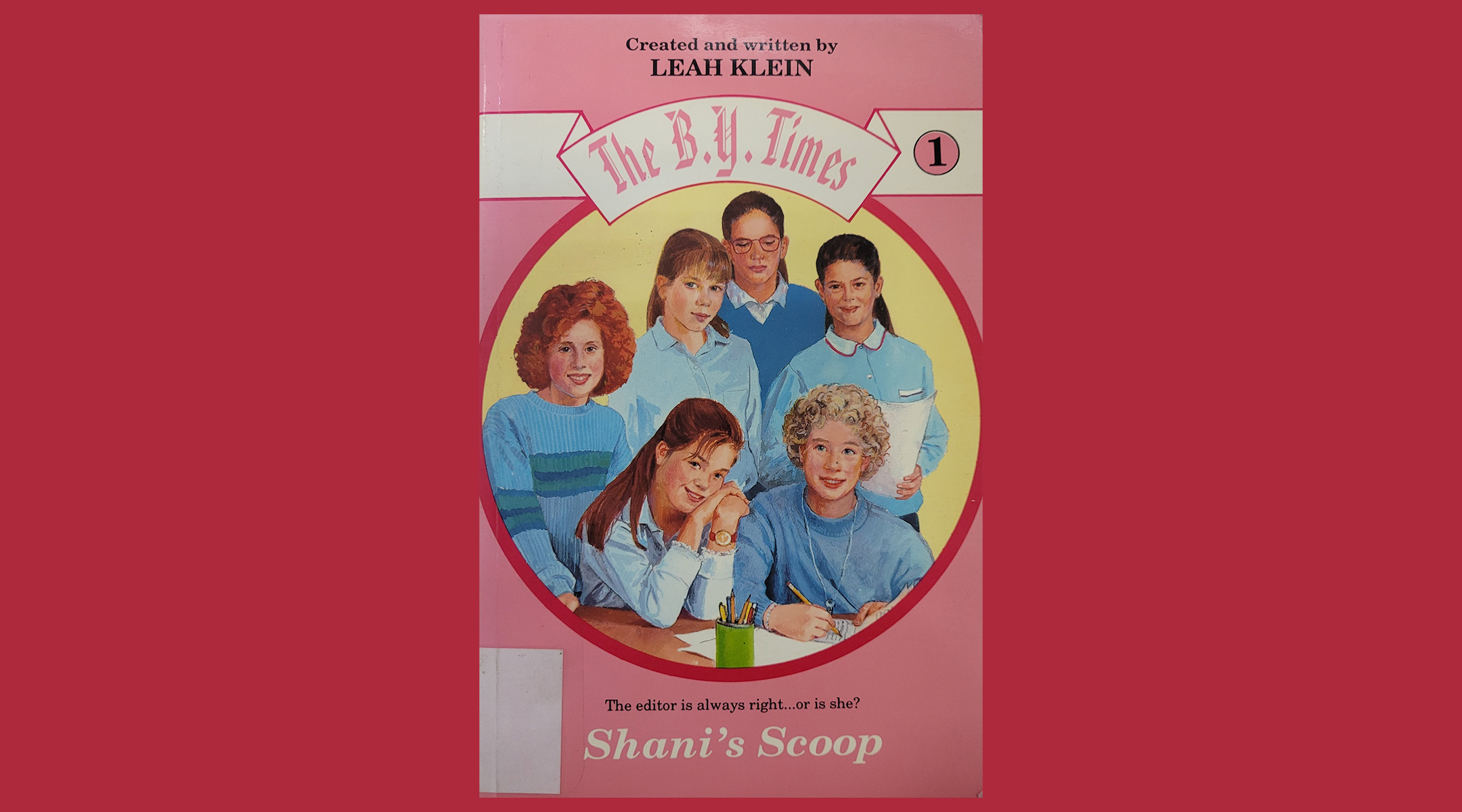

“The B.Y. Times” is a series of books, intended for the Orthodox young adult market, that is clearly inspired by the secular “The Babysitters Club” series (“sans boyfriends,” writes Meira Levinson, a professor of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education). (Courtesy Ben Yehuda Press)

It is also, for many of the contributors, a reckoning with a strictly Orthodox upbringing that many of them have left behind. The books, toys and songs are meant to reinforce values many of the authors find stifling, including strict gender segregation, narrowly prescribed roles for boys and girls and distrust of outsiders. Haredi book and toy stores, writes Shlomi Eiger, a Tel Aviv-based toy designer, “serve as gatekeepers, preventing secular consumer culture from infiltrating the community.”

Except when the gates don’t hold. Bernstein told me about the ways Orthodox publishers and creators can’t escape the culture that they are countering.

“This is a community that is not separate from non-Jewish America or from American politics,” Bernstein said. “They actively participate in American culture and American politics, for all their protestations to the contrary. If you actually look at the books, they are influenced by trends in American publishing.”

Examples include “The B.Y. Times,” a haredi version of “The Babysitters Club” books (“sans boyfriends,” as contributor Meira Levinson points out) and the “Devora Doresh” mystery series, a cross between “Nancy Drew” and, yes, “Encyclopedia Brown.”

For Orthodox parents and educators (and Bernstein acknowledges the wide range of philosophies and values within even the strictest Orthodox communities) the test of a children’s product is whether the creator has the right intentions. “If they don’t believe in the correct kind of Judaism, that will filter through in their work, and you will be influenced by that and you will therefore leave the correct kind of Judaism,” said Bernstein, characterizing the community ethos. “So it’s this idea of being very careful not to allow outside influences even if they seem harmless.”

And yet, as Levinson explains in her essay on the “Devora Doresh” books, (gently) subversive messages can slip past the gatekeepers: Created by Carol Korb Hubner, the books “feature an Orthodox Jewish girl having adventures of the kind that were otherwise normally limited either to Orthodox Jewish boys or non-Jewish girls.”

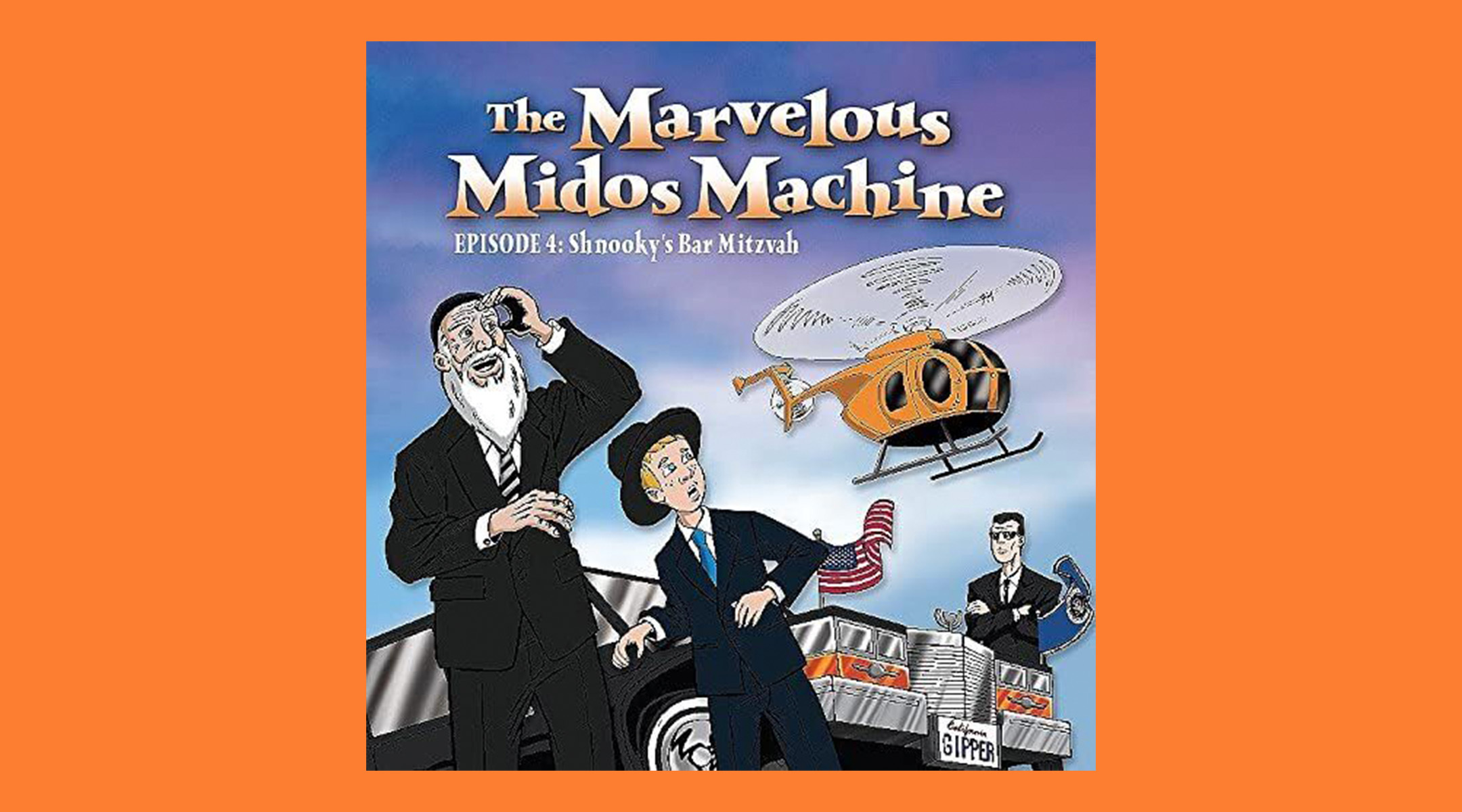

“The Marvelous Midos Machine” was a series of story albums released in the 1980s, featuring a rabbi-scientist who uses his knowledge of science to teach Jewish children to behave properly. The series “holds a special place in the canon of Orthodox Jewish story tapes,” writes a contributor to “Artifacts of Orthodox Childhoods.” (Courtesy Ben Yehuda Press)

Bernstein is a product of such boundary-crossing. Growing up in Borough Park, Bernstein attended Bais Yaakov schools, where Orthodox girls have to abide by strict dress and behavior codes. “I had to sign a list of things, saying that ‘I will not go to the public library. We do not have a TV in the house. There is no internet in the house except if you have permission from a rabbi for your work. You will not go ice skating. You will not go to visit Florida on midwinter vacation.’”

At the same time, Bernstein’s parents both had college degrees – unusual for the community – and allowed a limited diet of books from the public library. “I was as far as anyone could tell a model Bais Yaakov student,” said Bernstein, who nonetheless dove stealthily into books and even movies no haredi parent could ever allow.

Bernstein went on to Yavneh Seminary in Cleveland and came back to teach language arts at Bais Yaakov of Boro Park. “And then I went to college, which was a break from what was expected. And eventually I went on to grad school, and now I teach in college and research and hopefully publish.” Bernstein, who has a PhD in English and a certificate in medieval studies from the CUNY Graduate Center, left the haredi community while in grad school.

I shared with Bernstein my own qualms as an “outsider” who often writes and edits articles about the haredi Orthodox community for a largely non-haredi audience. Is “Artifacts of Orthodox Childhoods” meant to expose the community, and lead it to reform its insular ways? Are readers being invited to gawk at the peculiarly dressed men and women and their distinctive way of raising children?

“As a person, there’s a lot I would want to change” about the community, said Bernstein. “As a scholar, I know that it is useful to have things written about this world in a non-judgmental but still analytical lens. I want the non-haredi world to understand that these are complex people and to stop seeing it as such a completely foreign, exotic thing. And what I think it can do for the community is give them the tools that the leaders don’t always give them to look with a critical lens at these texts and artifacts and not just view them as inevitable.”

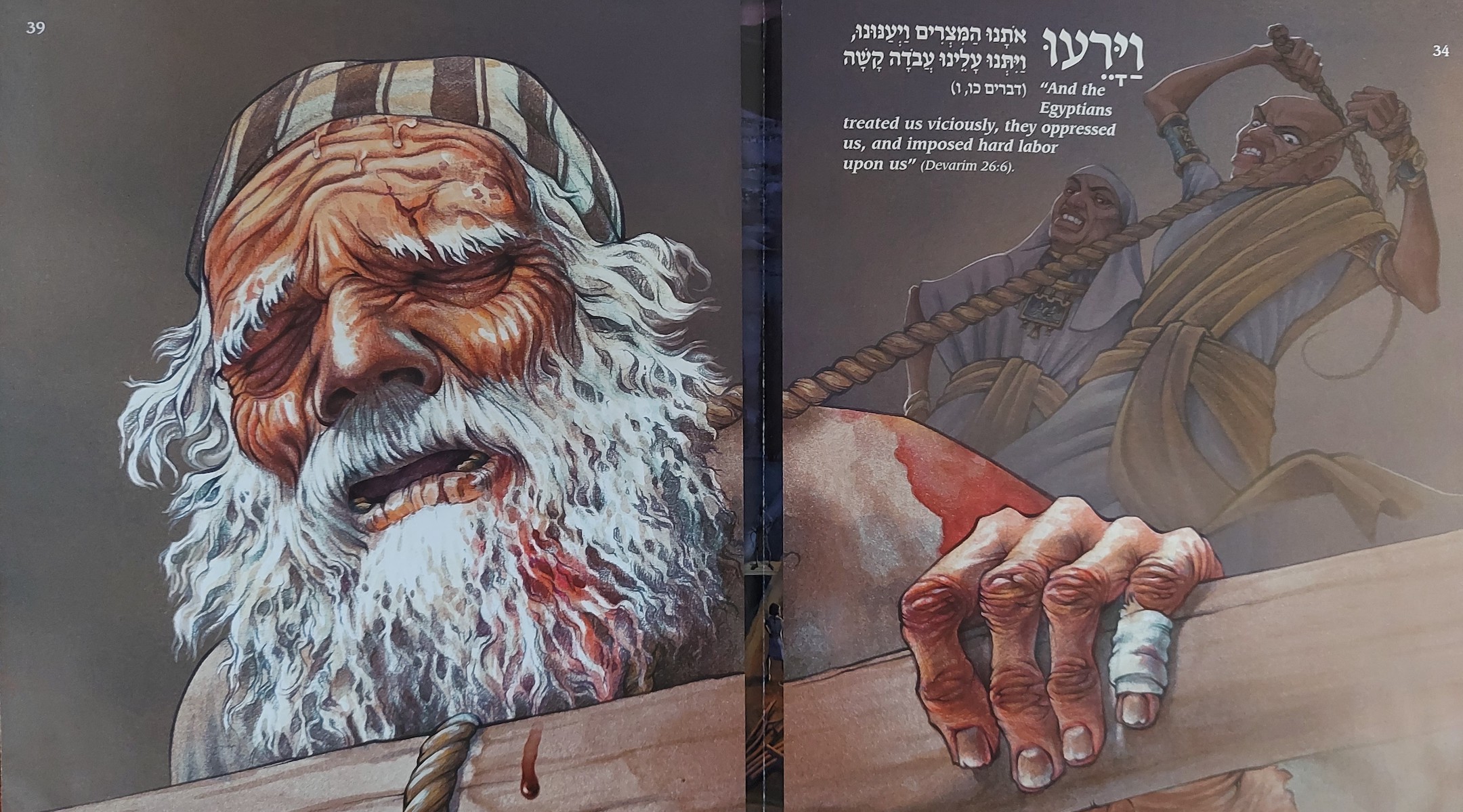

The graphic art in “The Katz Passover Haggadah,” published in 2003 and illustrated by Gadi Pollack, reinforces a haredi Orthodox worldview, writes Yoel Finkelman: “the outside world is not to be trusted, Jews can only rely on God, and sacrifice and suffering are part and parcel of Jewish experience.” (Courtesy Ben Yehuda Press)

In fact, the tone of most of the essays is wistful. Even in the scholarly essays the writers tend to look back with nostalgia on the moral certainty and idealized worldview they absorbed as children. A few writers share their childhood books and music with their own children. “As a mother,” writes Miriam Moster, in an essay about popular haredi boys choirs, “I want to raise my children in the tradition in which my personal narrative is rooted, but I also feel responsible to shield them from the facets that drove me to leave the Haredi community in the first place.”

Her solution could stand as a good description of Dainy Bernstein’s project: “And so I pass on to my children a potpourri of Haredi traditions, stories, rituals, and tunes that we interrogate and challenge together.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.