As the new Bob Dylan Center opens in Tulsa, a new pop culture mecca is born

Patti Smith, Mavis Staples and Elvis Costello were in town for the celebration; Dylan himself chose to skip it

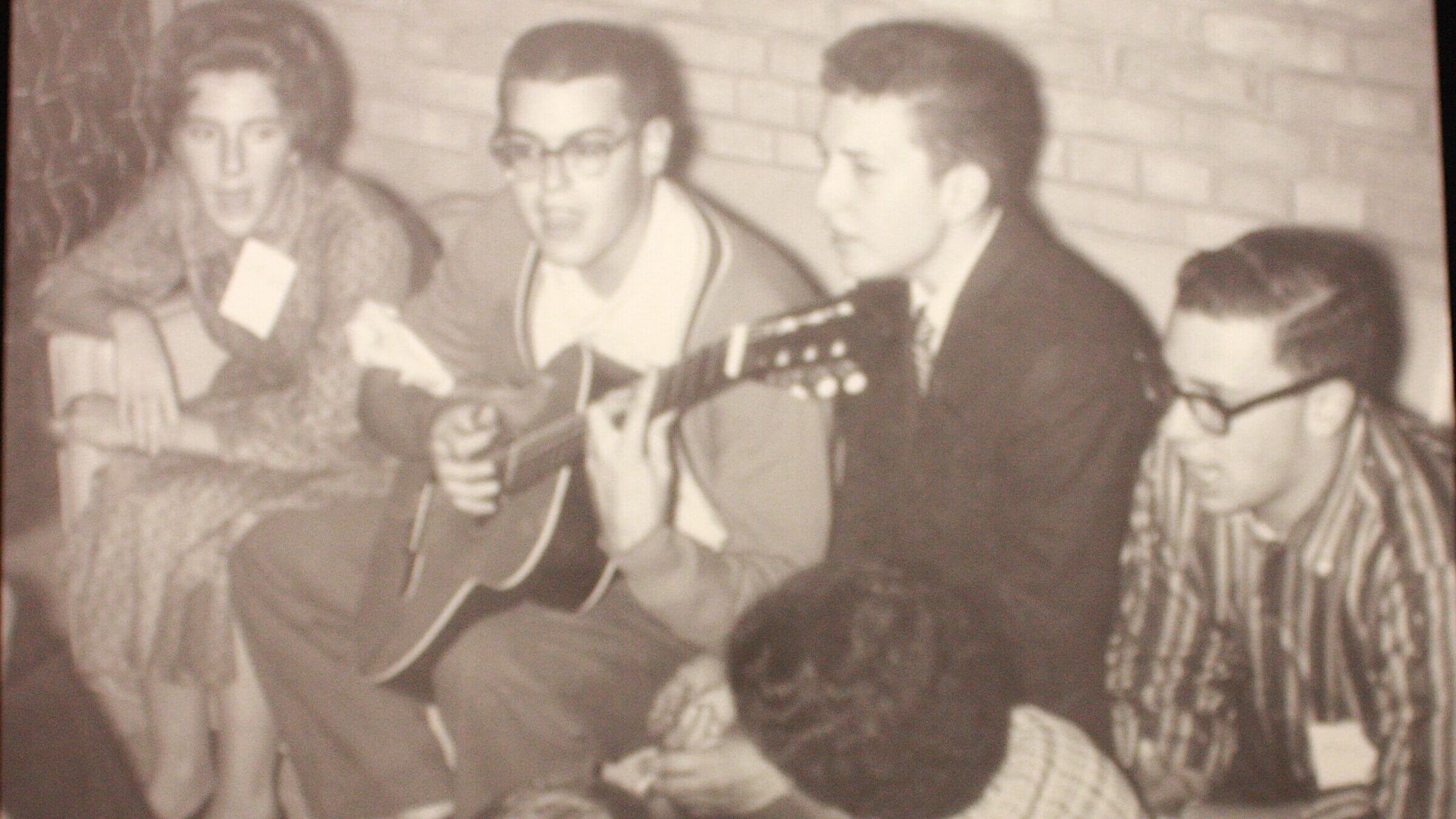

Robert Allen Zimmerman singing folk songs at the University of Minnesota Hillel House 1959 Photo by Seth Rogovoy/Courtesy of Bob Dylan Center

TULSA, Okla. – Duluth native Laura Whitney and her husband, Patrick Eliason, drove 835 miles — just over 12 hours — to be in Tulsa this past weekend for the opening of the new Bob Dylan Center and Archive.

Whitney counts herself as a lifelong Dylan fan. “I was reading his lyrics in my junior high school library,” she recalls. “I was probably 12, trying to decipher what they meant.” Coming from Duluth, Dylan’s birthplace, only added to her fascination with the Nobel Prize-winning song poet.

Later on in college, listening incessantly to “Like a Rolling Stone,” Whitney heard Dylan singing, “You’ve gone to the finest school all right, Miss Lonely, but you know you only used to get juiced in it.” Whitney took a hard look around her. “That was the seminal moment when I decided that I needed a break from college,” she said.

Eventually, Whitney met Eliason, himself a singer-songwriter and skilled craftsman. The couple are leading forces behind the annual Duluth Dylan Fest, which takes place this year from May 21 through May 29, encompassing Dylan’s 81st birthday May 24. They also wound up living full-time in Dylan’s hometown of Hibbing, Minnesota, for over a decade, during which time Eliason met a man named Bill Pagel, who wound up purchasing Dylan’s two childhood homes in Hibbing and Duluth.

Eliason now works with Pagel — who was also in Tulsa this weekend — carefully restoring the houses to the state they were in when Dylan lived in them. “I stripped the floors back to the original wood,” said Eliason. “You’re on the floor and you think, Bob walked on this. He probably toddled and crawled here.”

Theirs was not an atypical story among those VIPs who gathered for a sneak peek at the Dylan Center before it opens to the public Tuesday, May 10. Anne Margaret Daniel, a professor at the New School University (where she teaches courses on Dylan) and a writer and editor, arrived in Tulsa from her home in Woodstock, New York, representing another former Dylan hometown. On exhibit inside the center is rare “home movie” footage of a relaxed Dylan hanging out in Woodstock with family, friends, associates and fellow musicians in the late 1960s.

“It was wonderful to see the home movies of Dylan and Joan Baez at Albert Grossman’s home in Bearsville,” said Daniel, referring to Dylan’s one-time singing partner and paramour and his somewhat controversial manager. “Dylan playing by the pool, heading up to climb a tree, gassing up his celebrated motorcycle before driving it down Rock City Road — his Woodstock days, those days when he was a young father making music with Rick Danko, Richard Manuel and the guys in what would be soon called The Band, and with local friends like Happy and Artie Traum, and visitors like family friend George Harrison, seemed to be so happy for Dylan.”

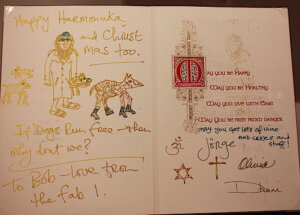

Dylan and the Beatles guitarist cemented their longstanding friendship and did occasional musical collaborations during Harrison’s visits to Woodstock. Evidence of that kinship is on display at the center, in several cards and letters Harrison wrote to Dylan over the years. In one holiday card, Harrison wrote: “Happy Harmonuka, and Christmas too. To Bob – love from the Fab 1.” Harrison included a sketch of Dylan wearing a yarmulke and a hand-drawn Star of David as well as other religious symbols underneath his signature. That Star of David recurs in another card from Harrison, in which he wrote: “Love to you & all the kids / grandkids / Sarah. Have fun – Shalom.”

There are hundreds of gems like these on display at the center and thousands more held in the private archive attached to the public exhibition space. There is a rare photo of Dylan and a group of fellow students casually singing folk music at the University of Minnesota’s Hillel House in September 1959. An Italian poster for Dylan’s experimental four-hour film, “Renaldo & Clara,” lists all the songs in the movie, including “Hava Nagilah.” The contents of Dylan’s wallet include Otis Redding’s business card and scrawled names and phone numbers for Johnny Cash and Lenny Bruce.

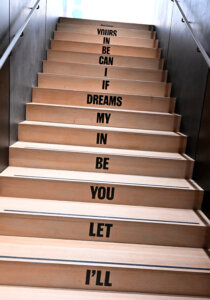

Original handwritten manuscripts of song lyrics replete with crossouts and revisions including “Chimes of Freedom,” “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Tangled Up in Blue” attest to Dylan’s perfectionism and belie the notion — at times perpetuated by Dylan himself — that the lyrics just come to him fully finished in a dreamlike state.

“To see a manuscript collection like this and to see the work in progress of Bob Dylan writing one set of lyrics and changing the whole thing — it’s really unbelievable,” said Bobby Livingston, who traveled to Tulsa from Boston, where he works at RR Auction, which frequently handles Dylanania. Livingston noted that the kind of handwritten manuscripts and letters on display are from a different, bygone era.

“People don’t write letters anymore,” said Livingston. “They send texts and emails. This is going to be lost, a lost art. Bob Dylan is probably the last person still writing on a notepad.”

Also on display is the guitar on which the opening, chiming chords to “Tangled Up in Blue,” widely regarded as one of Dylan’s greatest songs, were played. The guitar was a gift to the archive from Kevin Odegard, formerly of Minneapolis and now a resident of Florida, who also was in Tulsa for the opening. One day in December 1974, Odegard’s phone rang. On the other end was David Zimmerman, a local Minneapolis record producer, inquiring about the whereabouts of a specific model Martin guitar from 1937. Could Odegard, who had worked with Zimmerman previously, track one down?

Odegard suspected that Zimmerman was looking for the guitar on behalf of his brother, Bob Dylan. Not only did Odegard, himself a guitarist, track down almost the exact model of guitar; when he brought it to the recording studio, where Zimmerman had assembled a small group of musicians to help his brother re-record a handful of songs that were originally recorded in a New York City recording studio, Zimmerman suggested that Odegard hang on to the guitar and play it.

Dylan was unhappy with some of the arrangements laid down in New York City on what would become the album “Blood on the Tracks” — considered one of Dylan’s all-time greatest albums — and going back to Minneapolis and working with his brother proved to be an inspirational success. Those chiming chords that kick off the album on the opening number, “Tangled Up in Blue,” were played by Odegard, who recalled how midway through the song he and Dylan locked into a groove that was a musical conversation between two guitarists.

“We played on a masterpiece of heartbreak,” said Odegard, who wound up co-writing with Andy Gill “A Simple Twist of Fate,” a book about the making of the album. “[Bassist] Billy Peterson said it best: ‘I guess Bob liked what we did.’”

Also in town were three famous musicians who visited the center by day and performed concerts at Tulsa’s historic Cain’s Ballroom over three consecutive nights. All three have strong Dylan connections, having shared concert bills with him and varying degrees of friendship. Patti Smith and Elvis Costello peppered their sets with Dylan songs; the former opened her concert with a gorgeous acoustic rendition of “Boots of Spanish Leather” and tackled “The Wicked Messenger” and “One Too Many Mornings,” while the latter offered up his version of “I Threw It All Away” and a triumphant “Like a Rolling Stone.” Mavis Staples stuck mostly to her own repertoire but came closest to Dylan with a version of “The Weight” by The Band, Dylan’s sometime backing group.

Dylan, alas, was not in town this past weekend. He performed in Tulsa a few weeks back, and reportedly skipped a visit to the center, opting instead for a baseball game. The closest thing to a Dylan concert was a late-night underground club gig by New York City songwriter and music journalist Jeff Slate.

“If you wake up and you want to hear a great song, it’s Bob Dylan,” said Slate. “If you want to hear somebody who’s performing live and giving 100 percent of himself every time, it’s Bob Dylan. People complain about his voice, but it’s the most expressive instrument. I put him up there with Sam Cooke and Aretha Franklin. He means every word.”

It’s hard to say how many pilgrims will venture to Tulsa to walk through the exhibit hall at the Bob Dylan Center, but for real fans it is a visit well worth it. The Woody Guthrie Center, which also boasts original manuscripts, guitars and samples of Guthrie’s visual art, is just two doors down from the Dylan Center. At the moment, an exhibition hall dedicated to those who were influenced by Guthrie features a display of ephemera from well-known Guthrie acolyte Bruce Springsteen.

And on the outskirts of town you can visit the Church Studio, once owned and managed by sometime Dylan sideman Leon Russell. The studio is being faithfully restored to recapture the heyday of the Tulsa sound in the early 1970s as well as housing a brand new, state of the art recording studio, which contains the same control panel used to record Dylan’s career-reviving, Grammy Award-winning 1997 album “Time Out of Mind,” the cover image of which pictures Dylan seated in front of the very same panel.

For the most ardent Dylan fans, Tulsa will become a new mecca. But as much as the public displays and multimedia stations in the exhibition hall offer a dazzling, state-of-the-art journey into Dylan’s creative process over the course of his 60-year career, they are just the tip of the iceberg. The real work of the Dylan Center lies in the private archive, where 100,000 items have been organized and cataloged and will prove to be an invaluable resource for Dylan scholars, researchers, and writers for decades to come. Unbeknownst to and fortunately for us, Bob Dylan turns out to have been something of a hoarder and a pack rat, thereby providing the world with a road map to his artistic soul.

For anyone who believes that Dylan deserved his Nobel Prize for Literature, the center and archive are befitting, living monuments to the artist who changed the very sound and potential and purpose of modern popular song, along the way suggesting new ways to live and to challenge one’s point of view: to embrace a world that is, for better or worse, tangled up in blue. Which is why I probably will wind up back in Tulsa before too long. That’s a sentence I never thought I would write. But that is also a testament to a song-poet and modern-day prophet who, alluding to Walt Whitman, acknowledges that he contains multitudes.

Seth Rogovoy is a contributing editor to the Forward and the author of “Bob Dylan: Prophet Mystic Poet” (Scribner, 2009).