Why there is no holiday more tragic than Lag B’Omer for my family

79 years ago, much of Ann Weiss’ family was murdered by the Nazis

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Lag B’Omer is traditionally a happy festival when Jews celebrate with bonfires and picnics, but I have always known it as the day when most of my mother’s family was murdered.

My mother, Lunia Athalie Backenroth Gartner Weiss, came from the Gartner family, which was well-known for philanthropy. The Gartners built the theater in Stryj, Poland — now Ukraine — and a hospital wing dedicated to the care of women and children. They were also prodigious Torah scholars — particularly Shamei and Naftali. (My mother’s maternal family, the Backenroths, is the subject of Israeli journalist Michael Karpin’s “Tightrope: Six Centuries of a Jewish Dynasty” and is featured in Yaffa Eliach’s “Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust.”)

In 1943, on Erev Lag B’Omer, the family of Shamei Gartner (including his wife, his daughters, sons, all their spouses and all their children — among them, my grandfather Naftali, after whom my 5 year old grandchild in Israel is named, and my grandmother, Chana, after whom I am named) were all murdered.

The Nazis routinely “celebrated” Jewish holidays with extra aktions against the Jews, and this holiday was no exception.

As my mom often explained, the most important thing during these aktions “where the Nazis tried to catch every Jew” was “not to let the Nazis get their hands on you.” Therefore, it was imperative to hide. My mom’s Gartner family hired an architect to design a secret bunker, so secret that only members of the family were allowed to build it and know its location. It was so well stocked that, despite the starvation rampant in the ghetto, the whole family could have survived there for many weeks.

The hiding place was a room behind a hearth with a false wall; in the hearth was a big cauldron of water with a few potato shavings floating on the top — as if they were making soup. Before each aktion, the men in the Gartner Family drew lots; the one who got the short straw closed up the false wall and climbed above in the rafters. This person was totally exposed, if any of the Nazis happened to look up, but that was the system — one was vulnerable in order to save the others.

During one aktion, maybe a week or so before, many people were running to escape the clutches of the Nazis. Shamei Gartner was among them. Mom described him as having a long, flowing white beard, soft, kind eyes and a ready smile. “To me, he looked a modern-day Moses,” she said.

While everyone, including Shamei and his daughters, was running away from the Nazis, Shamei noticed a young man near them who was running too. “We must take him in too,” he told his daughter (my mother’s aunt), who was frantic, knowing how crucial it was that the location of the bunker be kept secret.

“The Nazis have taken everything away from us, but I won’t let them take away my ‘menshlichkeit’ (‘humanity’),” Shamei said simply. “If he doesn’t come in, I won’t come in.” With anguish, his daughter relented, and everyone was saved.

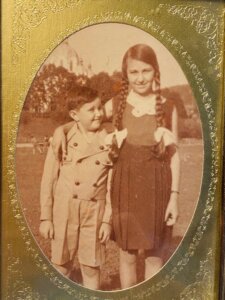

During the next aktion, most of the Gartner family ran and managed to hide in the bunker. My mother and her little brother, Zvi, were too far away and they didn’t make it there, so they found somewhere else to hide — which was why neither was in the bunker when an uncle witnessed this devastating scene: He saw the same young man, the one Shamei Gartner had saved, leading the Nazis to the bunker.

“Want to see a bunch of rich Jews?” the young man asked — which is how all of the Gartner family — mothers, fathers, children and grandparents — were all led away and murdered in a pit.

It has been 79 years since that awful day. I often think of Shamei Gartner, the man whose kindness and ethics saved that young man from the Nazis — and I feel so proud to be related to him. But then I also think of Shamei Gartner, a man whose ethics and humanity were much too good for that brutal world, and I wonder if, had he been less righteous, if I actually would have been lucky enough to know any of these relatives. Thanks to my mom and her many stories — always told with love — my sister, my two daughters and I almost feel as if we do.

Today, and many days, may their memories be for a blessing. Today and many other days, I know that they truly are.

Ann Weiss, Ph.D., is the author of “The Last Album: Eyes from the Ashes of Auschwitz-Birkenau,” the curator of a traveling photographic exhibition, a filmmaker, an educator, and an interviewer for the Transcending Trauma Project. She is also the Founding Director of Eyes from the Ashes, an educational nonprofit. For further information, please see: www.thelastalbum.org.