How the grandson of Jewish diamond dealers created the greatest rock ’n’ roll swindle of all time

There was method to the madness of the Sex Pistols — and his name was Malcolm McLaren

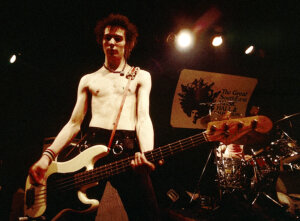

Malcolm McLaren, seen during the time when he managed the Sex Pistols. Photo by Getty Images

Malcolm McLaren, the creator of the Sex Pistols, built a voluminous, if tattered, resume over his many years in the music business. Among the terms that were applied: impresario, visionary, charlatan, anarchist, master manipulator, and plunderer of other people’s ideas and cultures.

Given the opportunity, he didn’t care to counter any of those perceptions.

“I don’t know what else to do!” McLaren told me with a laugh, copping to any and all charges, equal parts confessing and crowing. It was early 1985 and we were having afternoon drinks on the balcony of the Hoodoo Barbecue, the restaurant above The Rat, a Boston punk rock club.

“I take what I think is good and I remake it and make it work again,” he said. “I manipulated disasters and turned them into successes. I left people with a lot more than I took.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9KhxwG0eCiE

Interest in McLaren and the Sex Pistols is spiking again as “Pistol,” Danny Boyle’s miniseries, launches on FX via Hulu May 31. “Pistol” is based, mostly, on guitarist Steve Jones’ 2017 memoir, “Lonely Boy: Tales from a Sex Pistol.” But there are many scenes in the series that Jones could not have witnessed.

The battle for control of the band, as well as the band’s image and message, is central to the story, and it comes down to a clash between McLaren and singer Johnny Rotten. Yes, it started out as Jones’ band — along with his drummer pal Paul Cook and then original bassist-songwriter Glen Matlock. But ultimately it would belong to Rotten, who became the public face of punk. It was a band that McLaren both managed wily and willfully mismanaged.

When McLaren and I spoke, it was just seven years after I’d seen the Sex Pistols in Atlanta at the Great Southeast Music Hall, a club at the corner of a shopping mall. It had been their U.S. debut and it was ferocious fun, all amped-up anger and explosive catharsis, but the Sex Pistols were doomed, crashing and burning at the end of that tour.

McLaren, who wasn’t with them on that tour, had routed them through the American South, thinking that’s where they’d be most hated and could do the most damage. He wasn’t altogether wrong. There were genuine Sex Pistols fans in the U.S. — I met 500 rabid ones in Atlanta — but McLaren was spot-on in terms of mainstream media coverage and ordinary people who were offended by the snot and vitriol of these young English upstarts.

That tour concluded in San Francisco at Winterland, with singer Johnny Rotten prowling a debris-ridden stage, leaving the audience with the taunt, “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?”

Sure, it ended in chaos and lawsuits and the heroin overdose death of bassist Sid Vicious after he allegedly stabbed girlfriend Nancy Spungen to death. But when we spoke, McLaren wistfully recalled the band’s formative days.

“How can I create such poisonous and virile frenzy?” he asked. “The chemistry was perfect. The concept was brilliant, just brilliant! I had all the ideas, with Rotten picking up on them. And I had the best soldiers possible, all of them hating each other. We were bound together: We all hated everything that came before.”

In person, McLaren seemed very much like the character portrayed in “Pistol” by Thomas Brodie-Sangster, best known for his role as Benny in “Queen’s Gambit.” McLaren was — and Brodie-Sangster plays him as — an alternately charming and abrasive man, an elfin fellow with a shock of wild, curly reddish hair. He was an enthusiastic and bombastic wordsmith who wore his pretentiousness proudly. He touted cultural revolution and reveled in making, as he liked to put it, “cash from chaos.”

McLaren was born into an upper-middle-class family in London, the son of Scottish-born engineer Peter McLaren and Emily Isaacs, whose parents, Mick Isaacs and Rose Corré Isaacs, were Sephardic Jewish diamond dealers. It was his grandmother, Corré Isaacs, who primarily raised him. According to former McLaren colleague Mark Beasley, writing in Frieze, Corré Isaacs taught him “to be bad is good” and “to be good is simply boring.”

As far as his relationship with his mum, Emily, goes, suffice it to say that it was not a loving one. In 1984, Judy Vermorel, who was co-writing a book about the Sex Pistols with her then-husband Fred, told the Daily Standard, “We’ve talked to Malcolm’s mum. Even she doesn’t like him.”

When I relayed this quote to McLaren, he cackled for nearly a half-minute. Settling down to ponder the thought, he said, “Well, it might be true.” Then again, he reasoned, “I haven’t seen my mother for 17 years. I don’t know what the hell she thinks about me, and personally I don’t bloody care. She’s stupid.”

McLaren seemed happiest when talking about pop music in terms of creating “chaos” and “frenzy”; he was most bitter when he talked about prepackaged pop music, as he felt most of it had become.

“I don’t mind telling everybody off,” McLaren said. “I don’t mind opening the can of worms, I don’t mind not having a relaxing time. I don’t mind not rubbing shoulders with people, and I don’t mind not shaking hands. And I don’t mind a bit of fisticuffs.”

Many saw the symbiotic, if acrid, relationship between McLaren and Rotten — who was born John Lydon and has used that name in his subsequent band Public Image, Ltd. — as an older brother-younger brother relationship or mentor and protege. Rotten always disputed that and, after the Sex Pistols implosion, he fired many a nasty word McLaren’s way, at one point calling him “the most evil man in the world.”

Given that, Lydon was sanguine when McLaren died. “For me, Malc was always entertaining, and I hope you remember that,” he said. “Above all else he was an entertainer and I will miss him, and so should you.”

McLaren was entertaining. Peppering his discourse with four-letter words, he gave the impression that he was in on life’s little jokes and — if you had the time — was willing to share the punch lines.

After the Sex Pistols imploded, McLaren labored on “The Great Rock ’n’ Roll Swindle,” a movie directed by Julien Temple, intending to reconstruct the Sex Pistols myth as to paint himself as the master manipulator.

“It was my fantasy,” McLaren told me. “Trying to blow your ego up to ridiculous proportions, going further beyond anything Fleet Street had conjured up.”

McLaren was always a man with a scheme. He was not a musician or much of a singer, but before the Pistols, he managed the glam/proto-punk New York Dolls in their final days, and post-Pistols, he was involved with some of Britain’s most trendy acts, including Boy George, Adam and the Ants and Bow Wow Wow, the latter of which was fronted by a scantily clad 15-year-old singer named Annabella Lwin, which left him feeling an uncharacteristic twinge of guilt.

“I’m just a lecherous lunatic,” he said. “She didn’t want to do this. She really would be just as at home singing out-of-tune Stevie Wonder songs.” McLaren said his experience with Bow Wow Wow led him to consider getting out of the business altogether.

He didn’t. Improbably enough, McLaren became a recording artist in his own right in 1983. “Duck Rock,” his first album, was an eclectic electro-pop and rap album. ”Fans,” his second, was one of the more bizarre concoctions of its time, an album of classical opera set to electro- pop music. McLaren wrote his own rap to Puccini’s “The Children’s Chorus,” retitled “Boys Chorus.”

“All work and no joy makes Malc — and every other kind of hack — a dull boy,” he said.

In 1999, he ran for mayor of London. He did not win. He moved to Los Angeles and worked as an “ideas” consultant for Stephen Spielberg, though it appears none of those ideas came to fruition. He released his final album, “Tranquilize,” in 2005.

In 2010, he died in a Switzerland clinic, suffering from the rare cancer mesothelioma. At his side were his son, Joseph Corré, and his girlfriend of 12 years, Young Kim.

At that long-ago afternoon session of beers and chat, McLaren told me, “There’s a pattern that seems to be developing in the way I work, right from the Sex Pistols onward. And that pattern seems to me always dealing with something old, with a root, and then turning it upside down and making it new again.”

I asked him if he thought of himself as a thief.

“Inspiration doesn’t come out of thin air,” he said. “Might as well say to Picasso: ‘Hey, man, you just ripped off all that African sculpture.’ ‘Of course,’ Picasso would agree. ‘I wish I could rip off more. Isn’t it fabulous?’”

/* ——-05.31.22 Request From Jay MHD-4438 ——- */