In Argentina, a search for a Jewish rebel who became one of the ‘disappeared’

Marc Raboy’s ‘Looking for Alicia’ recounts a history of fascism through the story of a single murder victim

A girl holds a banner reading “Memory, Truth, Justice” next to a large banner with portraits of people disappeared during the military dictatorship (1976-1983), at a gathering to commemorate the 46th anniversary of the coup, at Plaza de Mayo Square in Buenos Aires. Photo by Getty Images

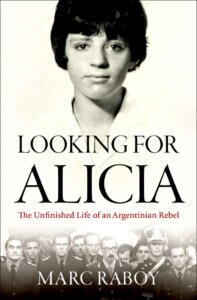

Looking for Alicia: The Unfinished Life of an Argentinian Rebel

By Marc Raboy

Oxford University Press, 310 pages, $27.95

The politics of memory remain raw and vibrant in Argentina. Every Thursday at the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, two different factions of bereaved mothers and grandmothers still march to demand justice for the desaparecidos, “disappeared” by the military junta of 1976-83.

In a residential neighborhood of this beautiful Baroque city, an old Argentine Navy school used as a clandestine detention and torture facility has become a historic site with exhibitions about this period of state terror.

The spectacular Parque de la Memoria, along the Rio de la Plata, contains a sculpture garden commemorating the tragedy and a memorial listing the murdered and missing. Here, too, the site’s dark history adds emotional resonance. One statue in the river faces the watery expanse where many of the regime’s victims were dropped, alive or dead, never to be recovered.

I first visited Argentina early in 1985. After seven years of dictatorship, democracy had resurged with the election of Raúl Alfonsín as president. “Nunca Más” (“Never Again”), the 1984 report of the commission investigating the junta’s crimes, was available at every corner newsstand. Spearheaded by the novelist Ernesto Sabato, that swift and detailed, if necessarily incomplete, historical indictment seemed extraordinary — as though Germany had published a compendium of Holocaust fatalities in 1946.

In the decades that followed, Argentina, beset by economic and political turmoil, writhed cyclically through paroxysms of accountability and historical amnesia. Trials were held; generals sentenced and then released; amnesties declared and revoked. When I made a long-delayed return trip, in 2019, Alfonsín was entombed in Buenos Aires’s famous Recoleta Cemetery, the mothers were hawking souvenirs in the Plaza de Mayo, and the country’s attempts to reckon with its past — the abducted children and others still missing, the perpetrators still at large — remained agonized and ongoing.

Argentina’s torturous history has proved compelling for Marc Raboy, an emeritus professor of media studies at Montreal’s McGill University and author of “Looking for Alicia: The Unfinished Life of an Argentinian Rebel.” It’s an informative book, a bit plodding at times, but written with clarity and conviction.

Raboy’s goal is to elucidate the backstory of a single murder victim, Alicia Raboy — one among as many as 30,000 (a figure that remains contested, like much else about those years). He does his best to place Alicia, a remote relative who shares both his Ukrainian Jewish heritage and his birth year (1948), in political and historical context. Raboy also finds parallels between Alicia’s activism and his own brief career as a 1970s radical. Both of their families were uprooted from Ukraine by pogroms, but where they settled mattered; he survived, and she did not.

Raboy’s initial interest was stirred by a family anecdote. His paternal grandfather left Ukraine in 1908 to spend a year in Argentina, before returning home, marrying and immigrating to Canada. Through internet research, Raboy stumbled on Alicia and her fate: a June 1976 police abduction that led to her disappearance.

Not every victim of the military dictatorship was a political activist. The junta’s tactics of kidnapping, torture, detention and murder extended to anyone who expressed dissent, or who might, as well as their intimates and acquaintances. The terror became increasingly indiscriminate, evolving into what Sabato in the commission report called “a demented generalized repression.” Raboy notes that as many as 10% to 15% of Argentina’s desaparecidos were Jewish, even though Jews comprised less than 1% of the population.

Alicia was a committed member of the left-wing Montoneros, a revolutionary group that retreated underground in 1974 and was outlawed a year later. With her romantic partner, Francisco Urondo, known as Paco, a celebrated poet-activist, Alicia had just moved to Mendoza, a mountain town known for its wine industry.

Urondo was tasked with reviving the movement there, a mission the disapproving Raboy sees as both dangerous and impossible. He hypothesizes that the assignment was, at least in part, a punishment for Urondo’s extramarital entanglement with Alicia. The Montoneros, Raboy writes, were “a Stalinist organization, elitist, hierarchical, bureaucratic and authoritarian.”

Targeted in a police ambush while driving with his family, Urondo was killed. Alicia was captured, transported to a detention center, and never heard from again. Their infant daughter, Ángela, survived. Raised by maternal relatives, she eventually was reunited with her father’s family and wrote a memoir.

Raboy interviewed both Ángela and Alicia’s brother, Gabriel, as well as many of her old friends and political comrades, including the husband from whom she had separated. They uniformly describe a rebellious woman of fierce intelligence and loyalty, an engineering student and journalist influenced by Simone de Beauvoir’s 1949 feminist classic, “The Second Sex,” and dedicated to politics from her teenage years.

To Raboy, Alicia’s loyalty seemed misplaced, at least when it came to the Montoneros.

Argentinian politics is hugely complicated, difficult for an outsider to parse. (Raboy tries.) Since the middle of the 20th century, the homegrown movement called Peronism, named for General Juan Domingo Perón (1895-1974), has loomed large. For most Americans, the main point of reference is Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1978 musical, “Evita,” focused on the working-class appeal of Perón’s charismatic first wife.

A compound of nationalism and trade unionism, with tendencies toward both authoritarianism and social progressivism, Peronism traverses the political spectrum from right to left, and many of its conflicts have been internal. The Montoneros defined themselves initially as left-wing Peronists but also were influenced by Che Guevara and the Cuban Revolution. They accepted the necessity of armed struggle and became prime targets of right-wing death squads even before the junta formally assumed power in 1976.

Raboy can’t pinpoint exactly what happened to Alicia. Urondo’s killers, and presumably hers as well, finally were convicted in 2011. As for his distant cousin, “Alicia remains unknowable,” Raboy writes, unfairly dismissing his own prodigious research. “She left no trace whatsoever,” he writes, too, referring to her disappearance, not the emotional wounds of her survivors.

Maybe any epiphany is elusive. But in sketching the outlines of Alicia’s story, Raboy points us to other mysteries of Argentina’s 1970s and ’80s — thousands of them — still waiting to be solved.