A humongous retrospective honors the glorious career of an iconic Jewish photographer

William Klein’s humor and social conscience have informed his work since the 1940s

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Although the title “William Klein: YES” may seem elusive and provocative, it’s also totally appropriate for the glorious retrospective of Klein photographs, paintings and films that’s now running at the International Center of Photography through Sept. 12.

The multitalented, 94-year-old visionary artist has embraced life fully. Saying “Yes!” to any and all opportunities, as irrational or even pointless as some might have seemed, has been his deeply held philosophy. This attitude defined him as an artist and person, said David Campany, the British-born exhibit curator and lifelong admirer of Klein, who is also working on a book about the artist.

“He didn’t take anything too seriously,” Campany told me. “It was always, ‘Sure, why not?’”

Klein started his career as an abstract expressionist, then moved into figurative painting and later found his artistic identity in photography and filmmaking when his teacher Fernand Léger, the modernist painter, sculpture and filmmaker, suggested Klein give those mediums a shot.

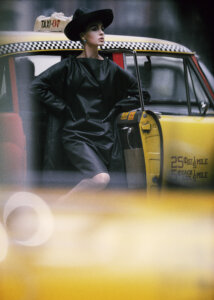

Similarly, when Vogue’s iconic editor Alexander Liberman offered Klein the chance to work for him, Klein was at the ready, even though, by his own admission, he had never taken a fashion pic in his life. And Klein’s forays into abstract photography, portraiture, documentaries and filmmaking were almost spawned, it seems, spontaneously.

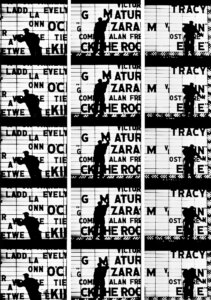

Featuring more than 300 pieces, the two-floor immersive, maximal exhibition at ICP chronologically explores Klein’s creative trajectory, subtly illustrating the interconnections — from his bold street photography in New York City, Paris, Rome, Moscow and Tokyo to his slyly absurdist fashion shots to his political documentaries on such iconic figures as Cassius Clay (before he became Muhammad Ali) and Eldridge Cleaver. Klein has also made narrative films, mostly in the satirical vein, that send up, among other topics, the fashion industry and American imperialism during the Vietnam War. “The Model Couple” (1958) is frighteningly prescient in anticipating reality TV. Looped film snippets projected on stark white walls are interspersed throughout the gallery.

Klein has had a major following abroad, but regrettably that’s not true in the U.S., where he is known by discrete audiences for his output in one or another genre, but not for his large body of work. According to Campany, “Yes” is a long overdue exhibit that will introduce many New York gallerygoers to a stunningly versatile artist who eludes easy understanding.

The Paris-based Klein, who no longer works and was too frail to be interviewed personally, nevertheless played a major role in overseeing the exhibit, which is located near where his Hungarian-born Jewish grandparents resided at the turn of the 20th century. “In some ways this is a homecoming for Klein, who has mostly lived abroad since the ’40s,” said Campany.

Although Klein’s grandparents were quite devout, Klein did not grow up with religion. Still, coming of age on West 110th Street in Manhattan, he identified as a Jew. Many nominally observant or, more often than not, secular Jews resided (still do) in that community. Klein saw himself as a part of the Jewish Diaspora and not surprisingly was interested in the lives of others.

“He understood the concept of displacement,” said Campany. “He always wanted to know where people came from and where they ended up and how history intrudes. I believe that comes from his Jewish background.”

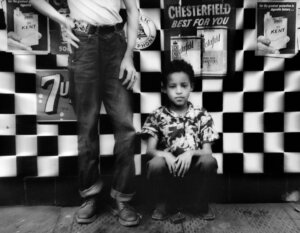

To what degree his work may be informed by his ethnic identity is not readily definable. Jeff Mermelstein, an ICP photographer who is well-versed in Klein’s work, said that there is “a particular energy and a pervasive anxiety, especially in his street shots, that I think reflects his Jewishness. Later, his connection with someone like Muhammad Ali may be part of that, too.”

“Klein did once make the remark that there were two forms of photography, two modes of dealing with subject matter,” Max Kozloff, an art historian, art critic, and photographer told me. “They were Jewish and Gentile. The Jewish work was more closely allied with jazz, nativism, folkloric traditions, religious ethnic identities, activism and social expression.”

Klein saw himself as a citizen of a global community. Even as a youngster he was fascinated by modern European art and spent many happy hours at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. He had his sights set on going abroad, and after serving a tour of duty in World War II he relocated to France where he launched his career as a painter and studied with Léger.

In 1947, he married Jeanne Florin, a Frenchwoman and fellow artist with whom he lived (tumultuously, suggests Kozloff) for 58 years until her death in 2005. She was his muse and influence, especially early on. She explored abstract photography, and Klein followed suit before branching out into street photography. His New York shots, taken in the 1950s and then in the 2010s are generally viewed as the major, if not the most significant, facet of his illustrious career.

“There was an enormous graphic energy in the work,” said Campany. “He never pretended to be objective. He felt it was an ethical problem to observe his subjects from afar and then put the camera in front of their faces without engaging them. He was very curious about his fellow human beings, interested in their interactions, among themselves and with him. They played up to him.”

Though he frequently photographed African American subjects, he was no social documentarian. Nevertheless, a political sensibility was implied. He was not presenting “victims or an underclass,” Campany said. “He was far more interested in the vitality and the wild excess of the picture. Unlike many other photos of the era, he did not frame his pictures in clean white borders. His was far closer to pop art energy. Subject and form were bound together.”

Either way, no American publisher would come near Klein’s 1956 book of New York street shots, “Life is Good and Good For You in New York — Trance Witness Revels,” though it was promptly published in Paris and today is considered a classic. More books featuring convention-breaking street shots followed: “Rome: A City and Its People” (1959), “Moscow” (1964) and “Tokyo” (1964).

“Europe was ahead of the curve, certainly compared to America,” said Mermelstein.

Beyond the opportunities and admiration he received abroad, which was not forthcoming at home, Klein had grown disaffected with America’s racial inequities and obsession with money and commercial success. Later, he was troubled by the Vietnam War. For Klein, life in exile made sense on many fronts, not least his image of himself as “an American in Paris,” said Campany. “He was an insider and an outsider.”

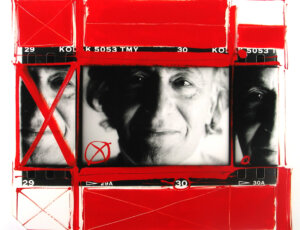

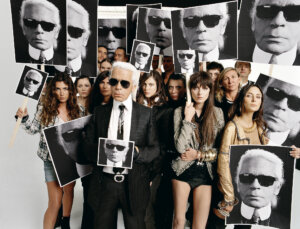

Artistic experimentation came naturally to Klein, the more irreverent the better. In some of his celebrity portraits, most notably a portrait of fashion mogul Karl Lagerfeld, he composed the piece with multiple Lagerfeld faces spread across the page at various angles.

“These portraits were alluring and silly and there was always that sense of playfulness,” said Campany.

Kozloff views Klein through a darker lens. In a 1981 piece, “William Klein and the Radioactive 50s,” written for Artforum, where Kozloff was executive editor, he suggested Klein was a bit of careerist, a “poseur,” and a voyeur whose work, often celebrating sleaze and scandal, appealed to other voyeurs. Still, he liked him, maintaining they had a good relationship because they accepted their differing viewpoints, personalities and functions.

“He was confrontational and collegial,” said Kozloff. “Despite a lack of finesse, Klein was intellectually probing, and erudite, without being a show-off.”

When Klein started doing fashion shoots for Vogue, once again he broke the rules, interacting with the models and encouraging their collaboration. In one instance, he photographed models parading through a crowded Italian thoroughfare toting mirrors — Dadaism meets improvisation.

In his dark 1966 film parody of the fashion world, “Who Are You Polly Maggoo?” Klein skewered the industry’s brutality and manipulation; the models’ frailty and vulnerability; the cult of personality and, most central, the pervasive materialism and out-of-control consumerism that characterized the culture at large. To this day, “Maggoo” has a cult following. (Over the course of the next three months, Klein’s movies will be shown at the Metrograph and Anthology Film Archives in partnership with the ICP).

Klein’s earliest film, “Broadway By Light,” a short cinematic montage of illuminated Times Square signage in 1958, was anointed by none other than Orson Welles, who said it was the first film ever that deserved to be made in color.

Klein trusted his own convictions. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Klein was fascinated by Muhammad Ali’s charisma, righteousness and outspoken views, and decided to make a film about him. On his flight to Miami to shoot the Ali-Sonny Liston fight, he found himself sitting next to Malcom X. By the time they disembarked, Klein had become part of Ali’s close entourage.

The film, “Muhammad Ali, The Greatest,” later retitled, “Float Like a Butterfly, Sting Like a Bee,” “is one of the greatest documentaries ever made,” said Campany. “It made Muhammad Ali an international superstar. Much of the Muhammad Ali footage that we’ve seen over the decades comes from that film.”

Klein was drawn to Black culture and politics, and the feelings seemed to be mutual. When Algiers was hosting a Pan-African arts festival, Klein was hired shoot the film. After that flick wrapped, Klein went on to make his film about Eldridge Cleaver; half of the film’s proceeds went to the Black Panthers.

Klein’s disaffection with U.S. policies at home and abroad continued to grow; some viewed his 1968 parody of American military might, “Mr. Freedom,” as an over-the-top bit of anti-Americanism.

“His criticisms are actually affection,” said Mermelstein. “It’s an expression of love to be candid about what you’re part of. It’s not uncommon for critics of American complacency to be accused of anti-Americanism.”

So, what will viewers walk away with after seeing the Klein retrospective? What will resonate long after the exhibit has come and gone? Campany has little doubt that Klein leaves a significant legacy and is hopeful that those who venture down to the Lower East Side to see the retrospective will appreciate Klein as he does.

“I’ve never known a person with such appetite for life, and such deep understanding of the complex forces that shape modern life: cultural, political, racial, economic, geographic,” he said. “Nothing seemed alien to him. He never became melancholy or a pessimist. Although he’s a realist there is a profound optimism in his outlook on life and art. As large as this exhibit is, we’ve only scratched the surface.”