Learning about antisemitism from the people who fought it

A London exhibit at the Wiener Holocaust Library examines the historical context of the world’s oldest hatred

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The Wiener Holocaust Library in London has a fascinating new exhibit on antisemitism powered by the idea that much of what we know about antisemitism comes from those fighting it. “Fighting Antisemitism from Dreyfus to Today” starts with the Dreyfus Affair of the 1890s, when Jewish army officer Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of treason, convicted and sentenced to life in prison in France, and ends in our current moment of resurgent antisemitism. To show how timely the exhibit is, it even includes a poster of a recent library exhibition on Kristallnacht that was defaced in the London Tube.

It’s impossible to take in this rich historical material without seeing connections between the framings of decades past and the rhetoric of today. The old canards that Jews control the world, rule the global monetary system, and are disloyal to their countries, repeat throughout the decades in an array of countries.

Supporters of Dreyfus were depicted as reptilian, to a degree that is shocking to look at. Just a few feet away, a 2012 mural by British street artist Mear One in London depicts Jews as demonic bankers oppressing people of color. The Jewish bankers in the mural sit at a table literally laid on the backs of Black and brown people. Mear One’s statement in response to objections from the Jewish community is included in the Library’s exhibit: “Some of the older white Jewish folk in the local community had an issue with me portraying their beloved #Rothschild or #Warburg etc as the demons they are.”

This statement is also discussed in “Jews Don’t Count,” British entertainer David Baddiel’s recent bestselling book on why Jews, a minority in Britain, are not viewed as a minority along with other marginalized groups. Baddiel spends six pages on the mural, which was taken down after the Jewish community complained. He finds politician Jeremy Corbyn’s reluctance to condemn the mural, as well as Mear One’s use of the word “white,” to be antisemitic. He also looks at how Mear One’s response uses internet culture, which is one of the main differences between antisemitism in the Dreyfus era and our own.

“Mear One’s own reaction to the buffing of his mural was instructive,” Baddiel writes. “Ignore the patronizing, Goebbels-like, insinuating tone — one that would never be used by anyone ‘woke’ toward any other ethnic minority — and instead consider why Mear decided to add hashtags to those names.

“It was posted on his Facebook page,” Baddiel writes, “and thus these hashtagged names can be clicked on. This means that Mear is not just saying: ‘I have painted Rothschild, the Jewish banking scion’, but: ‘I have painted Rothschild, the Jewish banking scion whose name you can now follow into the darkest corners of the internet, which will help you understand how this Jewish banking scion controls the world.”

The library has its roots in the work of Alfred Wiener, a German Jewish editor and activist who was alarmed by increasing antisemitism and collected evidence of the Nazi threat and the perilous situation of Jews in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s. Wiener and his family fled Germany in 1933 for Amsterdam, where he established the Jewish Central Information Office (JCIO), which collected information about the Nazis at the request of the Board of Deputies of British Jews and the Anglo-Jewish Association. After Kristallnacht, Wiener realized he could not stay in Amsterdam and prepared to move to the UK with his archive. It “is believed to have opened on the day the Nazis invaded Poland,” according to the library’s website.

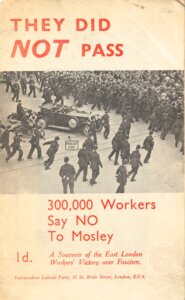

The “Fighting Antisemitism” exhibit focuses on three countries — France, Britain and Germany — and examines how “individuals, organisations and campaigns” worked to combat prejudice. One of the exhibit’s surprises is how it reveals behind-the-scenes work done by the Jewish community and busts some myths in the process. For example, during the leadup to World War II and during the Holocaust itself, the Board of Deputies of British Jews was accused of not doing enough, but the exhibit documents their extensive attendance at, monitoring of, and reporting on Fascist and antisemitic groups in Britain.

“Fighting Antisemitism” is curated by Dr. Barbara Warnock, who also wrote an accompanying catalogue, which makes for illuminating reading since all the information in the exhibit is hard to take in at once. The exhibit helps place the rise of antisemitism in the U.S. — and the collection of data on antisemitic incidents — in a more global context.

“State-orchestrated antisemitism such as that of the Nazis may be a thing of the past in Britain, France and Germany, but antisemitic ideas and antisemitic violence persist,” the exhibition catalogue notes. “The far right continues to hold racist ideas about Jews and to promote notions about ‘the Jews’ running global conspiracies to gain political and economic power, or to somehow ‘replace’ white communities with migrants. On the far left, it is common to find conspiracy theories associating Jews or ‘Zionists’ with capitalism and imperialist power. Islamic extremists claim that Jews are waging a war against Islam.”

One interesting point the catalogue makes is that Germany, Britain, and France gather statistics on antisemitic incidents in different ways. Some are state statistics; others are privately gathered. Americans reading news reports may want to keep these distinctions in mind.

In Germany, which recorded 1,898 antisemitic incidents in 2019, the state keeps official statistics on hate crimes — and these are referred to as “politically motivated criminality” (PMK). “Antisemitic incidents that are not designated as unlawful under German law would not appear in these statistics, nor would crimes not reported to the police. Recently, some regions in Germany have established a system to allow people to report incidents to an independent organization,” the catalogue explains.

Statistics on antisemitic incidents in Britain, by contrast, are gathered by the Community Security Trust, (CST), “a community-based monitoring organization funded almost entirely by donations from the Jewish community,” according to the catalogue. “CST encourages the Jewish community to report incidents to them, and the organization then uses its criteria to assess whether to designate incidents as antisemitic.” The CST recorded 2255 antisemitic incidents in the UK in 2021, the highest annual figure ever reported.

In France, where half of racist attacks target Jews even though they represent less than 1 percent of the population, statistics come from the French police. And the catalogue notes, “there is not a mechanism by which members of the public can report antisemitic incidents to an independent monitoring organization.”

For American visitors, this country-specific context on statistics and how information on antisemitism is recorded can be helpful in considering how the FBI gathers hate-crime statistics, and how American Jews can also turn to the Anti-Defamation League to report antisemitic incidents.

“Fighting Antisemitism” will be on view through Sept. 9, and the library will be hosting several events in conjunction with it. Admission is free.