Should Ivanka Trump sit shiva for her (non-Jewish) mother?

Ivana Trump died at age 73 on Thursday. Her death raises questions about the Jewish laws governing mourning practices for converts.

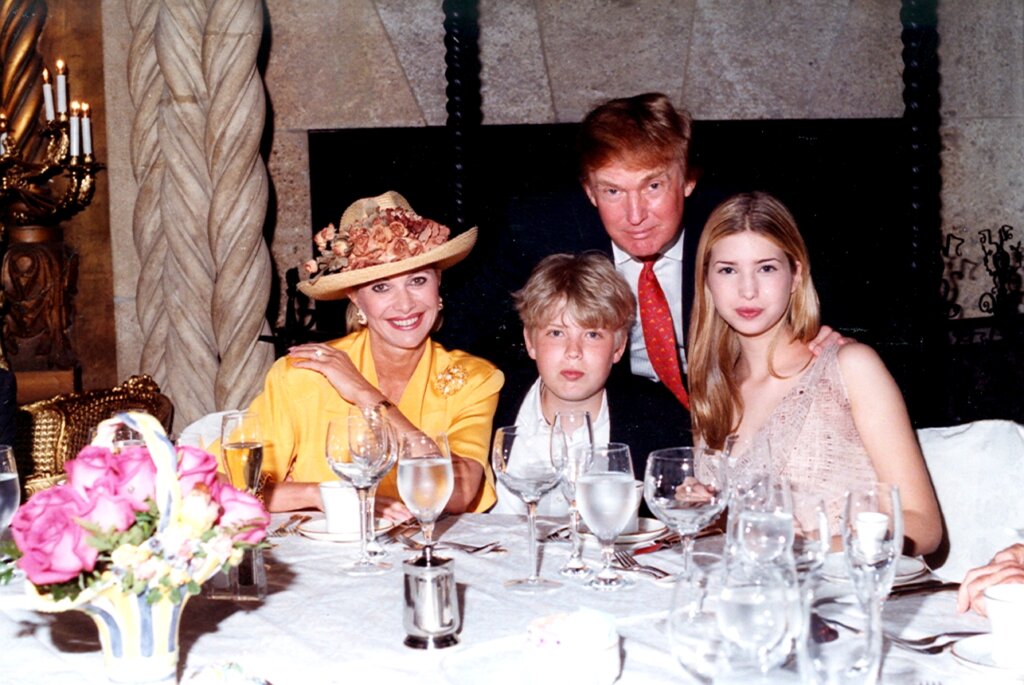

Ivana Trump 2018 Photo by Getty Images

Ivana Trump, the Czech first wife of Donald Trump and mother of Ivanka, Eric and Donald Jr., has died at 73.

Her death presents a question for Ivanka: How should she, as a convert who is now an Orthodox Jew, mourn her non-Jewish mother? Will she — and, Jewishly, is she allowed to — sit shiva?

Converts to Judaism are symbolically renamed the son or daughter of Abraham and Sarah, a gesture toward the idea that Jews are all the children of the patriarch and matriarch. In a strict interpretation of Jewish law, this functions as a nullification of your former life and parentage — now you’re a Jew, and your past life as a non-Jew is dissolved by the conversion. That means you’re certainly not obligated to sit shiva for your (non-Jewish) biological parents; religiously, at least, you don’t have any living parents.

But of course, that’s not how it usually feels. Ivanka Trump is clearly involved and attached to her non-Jewish family — look at how close she is to her father. And Jewish mourning rituals are made, in part, to help the bereaved process their loss.

Some authorities advise such survivors not to observe full Jewish mourning rituals so as to prevent anyone from accidentally thinking the person being mourned was Jewish. But everyone acknowledges that there’s real grief involved, and even the most stringent sources urge the convert-mourner to Jewishly mark the death in some way.

Rabbi Jon Leener, who leads a modern Orthodox congregation in Brooklyn, pointed out that most rabbinical authorities advise sensitivity to both mourners and converts, and rule that “discretionary mourning” — that is, ritually mourning someone you are not halachically obligated to mourn — should not be discouraged. In fact, if it will help the mourner, it should be actively encouraged.

Leener did note that there can be limits; some rabbis might take issue with reciting blessings that are not halachically required, such as the blessing made over a ritually torn garment Jewish mourners typically wear from the funeral through the seven-day shiva period.

“The language of the bracha is around being commanded, which is a problem if you’re actually not commanded to do so,” he explained.

But he said that saying kaddish and sitting shiva should not pose an issue, and that Jewish converts should be encouraged to use these rituals to mourn their parents in community.

Not everyone finds it quite so simple. The Aish and Chabad websites, for example, discourage full Jewish ritual observance for non-Jews. But even they urge the convert to find a Jewish way to mourn, such as reciting a psalm instead of kaddish, or reciting the kaddish but for only a month.

Halacha is not the only obstacle. For Yisrael Campbell, a comedian who grew up Catholic and now is a religious Jew, logistics made it tricky when his parents died.

Jewish tradition calls for burying the dead as quickly as possible, for example. But it can take days or even more than a week to bury the body with a non-Jewish funeral home and a family who doesn’t see the rush — six days for Campbell’s father, who died on an October Tuesday in 2009 and was buried the following Monday.

Campbell had to make his peace with what he called an “upside-down shiva,” where mourners and well-wishers poured through in the week before the burial instead of the week after.

Ivanka Trump will likely have to deal with a similar choice of how to observe, given that it has already been more than a day since her mother died and no funeral arrangements have been announced. Given the family’s celebrity, it may well take days for the high-profile mourners to gather. A traditional shiva seems unlikely, and she will need to choose which rituals she incorporates, and how.

If anything, the lack of halachic obligation can free Ivanka to do what feels meaningful and fitting, and not feel guilty about what doesn’t end up panning out amidst the hubbub and press coverage and various needs of other, non-Jewish relatives.

“I think that’s the beauty of not being bound by halacha,” said Campbell. “We don’t have to walk away from our families when we convert to Judaism.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture How one Jewish woman fought the Nazis — and helped found a new Italian republic

-

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

-

Fast Forward Betar ‘almost exclusively triggered’ former student’s detention, judge says

-

Fast Forward ‘Honey, he’s had enough of you’: Trump’s Middle East moves increasingly appear to sideline Israel

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.