Former White House speechwriter now singing a different tune in Boston

Joe Resnek’s first album, ‘1,’ reflects his roots in Chelsea, Massachusetts, a town formerly nicknamed ‘Little Jerusalem’

Joe Resnek traded law for music and is back in his native hometown of Chelsea. Courtesy of Joe Resnek

(Boston Jewish Journal) — A decade ago, Joe Resnek was a precocious 23-year-old with a hard-knocks background who’d graduated Harvard and talked his way into a job as a speechwriter for Obama administration big shots.

His goal – he’s big on goals – was to get into Harvard Law School. Which he did. Along the way, he founded the law school’s mock trial team, becoming the top-ranked student attorney on the national circuit.

Next goal: To become a public defender. “It’s because I played Atticus Finch in my high school production of “To Kill A Mockingbird,” he said in an interview, referring to the principled lawyer who championed racial justice in Harper Lee’s 1960 novel.

He accomplished this, too. For two-and-a half years, he represented drug offenders, drunk drivers, assault-and-battery suspects, and others who couldn’t afford a private attorney.

Resnek’s law school classmates, meanwhile, have gone on to judicial clerkships, to Wall Street, to elite law firms. So where is Resnek now?

Back in Chelsea, Massachusetts, where he grew up, rocking dreadlocks, hanging with his lifelong pals – and making music about life in the neighborhood. In June, he released his first album, which is called “1,” reflecting his roots in Chelsea, the smallest city geographically in Massachusetts at 2.46 square miles, where the per capita income hovers around $26,000.

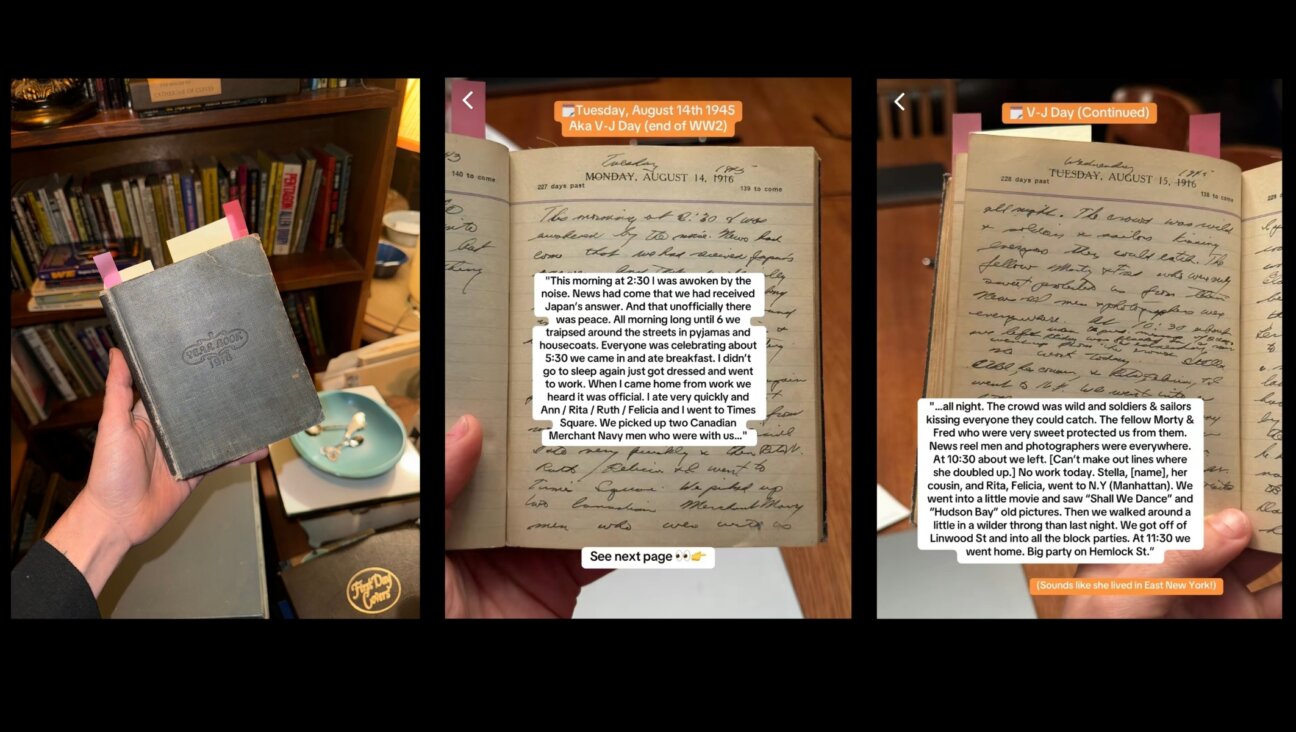

Nearly 70% of Chelsea’s population is Latino, bearing little resemblance to the community a century ago, when it was a working-class center of Jewish life. Back then, more than half the population identified as Jewish and Chelsea was nicknamed “Little Jerusalem.” Resnek’s Chelsea lineage goes back to 1885, when his great-great-grandfather Josiah came over from Belorussia and eventually ran a butcher shop.

He sings about leaving and coming home, about a shared vision of community, about hard-luck lives – in a kind of pop/rap genre that defies categorization.

He’s also released a couple of music videos, including one for a song called “Ghetto” where he hop-skips – singing – down Park Street.

Welfare case

Landlord chased

Working the block is the only hope anyone got at making it big …

Next goal? “Just trying to promote my music, and release more new music,” said Resnek, enjoying the night air on a bench at Mary O’Malley Park, named for a well-known matriarch of Chelsea. It overlooks the Mystic River, in the shadow of the Tobin Bridge. He loved being a public defender, he said, but “music led me here. I’m back.”

“It’s been quite a metamorphosis, or an evolution. Or both,” said his father, Joshua Resnek, publisher and editor of the Everett Leader Herald.

From ‘punk’ to ‘speechwriter’

I first met Resnek in 2012 when I interviewed him for a Boston Globe story about his unlikely ascendance from self-described “Chelsea punk” and low-level delinquent to a speechwriter for bureaucrats, cabinet heads, and ambassadors. An Obama appointee, Resnek spent a year and a half in the post, which he said gave him “a greater understanding of the workings of power in America.”

It was a long way from the Tobin Bridge. “When you’re from Chelsea, you’re kind of lucky to get to Everett,” he said at the time.

While he was in Cambridge attending Harvard, Chelsea stayed in his blood.

He stayed close to his buddies, sometimes jogging back from Harvard Square, crossing through four cities – Cambridge, Somerville, Charlestown, and Everett – to get home for Shabbat dinner.

His mother, Carol Resnek, traces his passion for music to the time she took him to a Sting concert when he was about 8. “We walked out of that concert and he looked up at me and said: ‘That just changed my life.’”

She bought him an electric guitar and amp, and soon he was writing his own music. In fifth grade, he started a band called Impulse with a guitarist he’d met at Hebrew School.

“We played over there,” he said, gesturing to the cement platform at the park. They played at Punks Corner at Revere Beach, and at school dances.

At Harvard, he put music aside to concentrate on his studies, but spent summers back in Chelsea, parked in his mother’s basement. “All he did was make beats, make beats, make beats,” she said. Towards the end of law school, he played in the streets around Harvard Square and downtown. The day someone gave him a $50 tip was “one of the greatest moments of my life.”

The day he was admitted to the Massachusetts bar, he applied for his first job as a public defender. He found one in Greenfield, where he didn’t know a soul but “the people in the system were really nice,” he said. “I got along really well with the clerks and the guards and the clients. It provided me with camaraderie.”

It also provided him with material:

Walkin outta jail ‘bout the best way to start the day

Look at the sun hittin’ the pavement, I got nothin’ bad to say

But lookin’ at my people in jail got me thinkin’ goddamn I should be

A little less concerned with my reputation, a little more grateful I’m free

He made music every minute he wasn’t doing law. And occasionally while he was doing law, after the pandemic started and court appearances moved to Zoom. One time he was waiting for his case to be called while editing a song on his computer. He thought he was on mute but the whole courtroom heard him rapping.

The judge wasn’t amused. But Resnek was delighted: the prosecutor asked where he could find that song on Spotify.

“Greenfield is where his hair grew out, where the real transformation took place,” Joshua Resnek said. “He rented a house and made a sound studio full of speakers, mics, guitar, drums, a piano. And that became his cause celebre. Greenfield was completely liberating for him.”

“He has this passion,” said his friend Gabe Cederberg, a musician who met Resnek at Harvard and has been helping him with production. “I know how much he toils over every single phrase.”

Connecting to his ancestors

Though the path he’s chosen might appear to be a disconnect from his former life, Resnek doesn’t see it that way. “It feels ‘from the bottom,’ like my Jewish ancestors coming to Chelsea selling pots and pans. I feel deeply connected to my ancestors who got their start here like I’m getting mine,” he wrote in an e-mail. “I believe I’m carrying on a tradition of ambition in my family. Whether that’s Jewish or not, I don’t know.”

He’s playing everywhere he can these days, including high-traffic tourist destinations and music venues. On Aug. 22, he’ll perform at the Midway Café in Jamaica Plain. His songs can be heard on several streaming platforms including Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon, and YouTube.

“I use the streets to practice and see what people respond to,” he said. It’s occurred to him that a song is a lot like a speech. “Moving a crowd is the principle,” he said. “Obama was a rock star – and not because he sang.”

A few days ago, he got his first $100 tip from a man who told him: “Use what you’ve been given to share your music with the world.”

“That’s a good sign,” Resnek said. “People being really moved by what I’m doing.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO