7 great new films from Israel coming soon to a (big or small) screen near you

Documentaries and social dramas were among the highlights at this year’s Jerusalem Film Festival

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The Jerusalem Film Festival has showcased the Israeli film industry for 39 years. The best entries circulate there before they arrive in the U.S. This year I saw several excellent candidates for international distribution.

Holocaust films

“June Zero,” a new Israeli-American film directed by Jake Paltrow (Gwyneth Paltrow’s brother) takes place in 1961. Adolf Eichmann, a major architect of the Holocaust, has been sentenced to death in Israel. The question is what to do with his body. Burial is not an option, lest his grave turn into a site of Nazi pilgrimage. Though the premise is grim, the film is delightful. The story is told from the point of view of 13-year-old David (the excellent Noam Ovadya). The son of new immigrants from Libya, David works at a factory to help out his family. Mechanically gifted, he becomes instrumental in the creation of a crematorium for Eichmann’s body.

Along with David’s fictional story, we get to look under the hood of history. The story of Eichmann’s guards is based on real-life events; concerned about vigilante revenge, every staff member who came in touch with the Nazi had to be verified non-Ashkenazi and non-survivor. As a result, the guards were Mizrahi Jews, whose characters allow the film to explore the unusual intersection of the Holocaust and Mizrahi identity. Paltrow denies Eichmann any screen time — we never see his face or even his body in full. He is very deliberately not a character. The character of David, though, will stay with you.

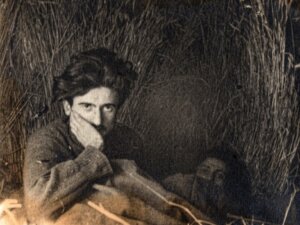

“The Partisan with the Leica Camera,” a documentary directed by Ruth Walk, takes a very different approach to history. It’s the story of Mundek Lukawiecki and his wife Hannah Bern, two of the very few Jews who fought in the Armia Krajowa, the Polish underground army killing Nazis and Polish collaborators.

Lukawiecki was assimilated, athletic and good-looking. Bern was from an Orthodox family. Nazi violence brings them together. When Bern, at 16, is raped by the Ukrainian police in the ghetto, her father pays Lukawiecki to take her with him to the forest. Bern undergoes transformation in a partisan camp. Fighting along with some 40 partisans, she faces sexual violence from them, too. She learns to kill. After the war, Lukawiecki and Bern arrive in newly-founded Israel and form a seemingly normal family. But the violence doesn’t leave them — the neighbors remember his screaming and her crying, a soundtrack of violated life.

We learn this story not only from recollections, but from Lukawiecki’s photographs — he picked up a camera when he was a young man and never put it down, even when documenting underground fighting was potentially deadly. His extraordinary photographs are overlaid with footage of the forest in motion. The characters in the photos gradually dissolve, becoming ghostly presences, and then disappear completely. The images linger in our memory long after.

Hot topics

A number of festival films this year explored social issues such as #MeToo, race relations and police violence. “Barren,” directed by Orthodox filmmaker Mordechai Vardi, has all the elements of recent Haredi dramas: a childless couple desperate for good news, an overbearing mother, a devout father. And yet, the film veers into unusual territory.

When a young husband travels to Uman, he leaves his wife Feige with his parents. Her in-laws welcome to the house a saintly man, a miracle-worker with a shofar. Things get uncomfortable very soon, when the guest suggests that Feige hold his shofar: “Feel it,” he orders.

The shofar is enormous, its phallic power obvious and repulsive. When the “tikkun” doesn’t work, the man steals into Feige’s bedroom at night to try other means. What unfolds in the aftermath of the assault is a nuanced drama, challenging both the family dynamic and religious institutions. Mili Eshet, as Feige, steals the show: her eyes are luminous; her elfin figure expresses shame, pain, and ultimately, hope.

“All I Can Do,” by Shiri Nevo Fridental, focuses on the legal aspects of sexual violence. A young woman, Efrat (Sharon Stribman), sues a man who sexually assaulted her when she was a teen. Reut (Ania Bukstein) is a public prosecutor on her case. The case is old and relies solely on testimony and character, a fact exploited by a manipulative defense.

It goes as expected: Efrat is rebellious but unstable. Reut is reserved at first, but then gets emotionally involved, as she discovers her own vulnerabilities and family secrets. Despite being predictable, the film is worth watching. The acting is superb and the court scenes feel authentic — not surprising because Fridental was a lawyer before she turned to film.

“Concerned Citizen” by Idan Haguel contends with gentrification, police brutality and liberal guilt in a way that feels fresh and uncompromising. A gay yuppie couple moves into southern Tel Aviv, a neighborhood of migrant workers and African refugees. Ben (Shlomi Bertonov) tries to do good. He cleans up human feces in his entrance hall, heads the housing committee, and even plants a tree next to his building. But when police responding to Ben’s call beat an Eritrean migrant to death, Ben fails to act. Instead, he goes on a guilt trip, taking us with him, and ultimately arrives at the place where he can forgive himself — but we can’t.

The story is told in a series of scenes, many of them darkly funny. But Haguel cuts away from them abruptly before sarcasm turns into comedy. He keeps landing us on a blank screen to remind us that we are watching his film, and that once it’s over we have to face our own moral choices, not just feel superior to Ben’s.

Perspective on America

While not an “issue film,” Ofir Raul Graizer’s “America” also engages with charged themes of violence and racism. The film opens with Eli (Michael Moshonov) living in the U.S., to which he escaped after his ex-cop father killed his mother. Now the father has died and Eli returns to Israel for the inheritance. The plot springs into action when he meets with his childhood friend Yotam and Yotam’s fiancee Iris (a revelatory Oshrat Ingedashet), and a freak accident changes the course of their lives.

What follows is a melodrama with a love triangle, entangled histories and unhealed traumas. Without being political, “America” quietly touches on the difficult realities of life in Israel. Eli’s story explores toxic militarist masculinity. Iris is an Ethiopian Israeli and the racism she encounters becomes part of her story.

Aside from its stirring plot, this film’s biggest achievement is its expressive cinematography. Eli’s lonely life in Chicago is filmed in blue and indigo. The palette changes to grey and brown once he enters the oppressive atmosphere of his father’s house. The screen bursts with colors in the house of Iris and Yotam, awash in yellow and red, and in their flower shop overflowing with green, pink, and purple. With its precise attention to textures and colors, “America” is a feast for the eyes.

The festival’s biggest revelation

“The Soldier’s Opinion,” by Assaf Banitt, based on the book by Shay Hazkani, is a documentary about military censorship in Israel. For 50 years, from 1948 to 1998, the IDF maintained a special department tasked with perusing every single letter sent by every single soldier — ostensibly, to monitor for military secrets, but in reality, as the censors themselves admit, as a means of mind control.

The censors wrote detailed reports on soldiers’ opinions, which, at times, influenced policies. More often, these reports provided to higher ups intelligence on private infringements, including homosexuality (which was criminalized), drug abuse, health issues and moral quandaries. What emerges in the reports are doubts about the morality of Israel’s wars, accounts of plundering, even parallels between the Nazi treatment of Jews and the IDF’s treatment of the Palestinians.

The film generously quotes the soldiers’ letters, on which the reports are based, revealing an honest and painful commentary on Israel’s wars. In a mere 55 minutes, the film succeeds in bringing together the letters and reports illustrated using rare archival footage, interviews with the censors, talking heads of scholars, and even a reconciliation between a former soldier and a former censor.

Today, even as cell phones put an end to letter writing, the censorship continues. IDF censors monitor soldiers’ minds and hearts via social media. This eye-opening film, at times moving and at times devastating, is a must-see.