The Jewish afterlife: How New York preserves memories across generations

How a great-uncle’s death and an ice cream flavor got me thinking about the phrase ‘may their memory be for a blessing’

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

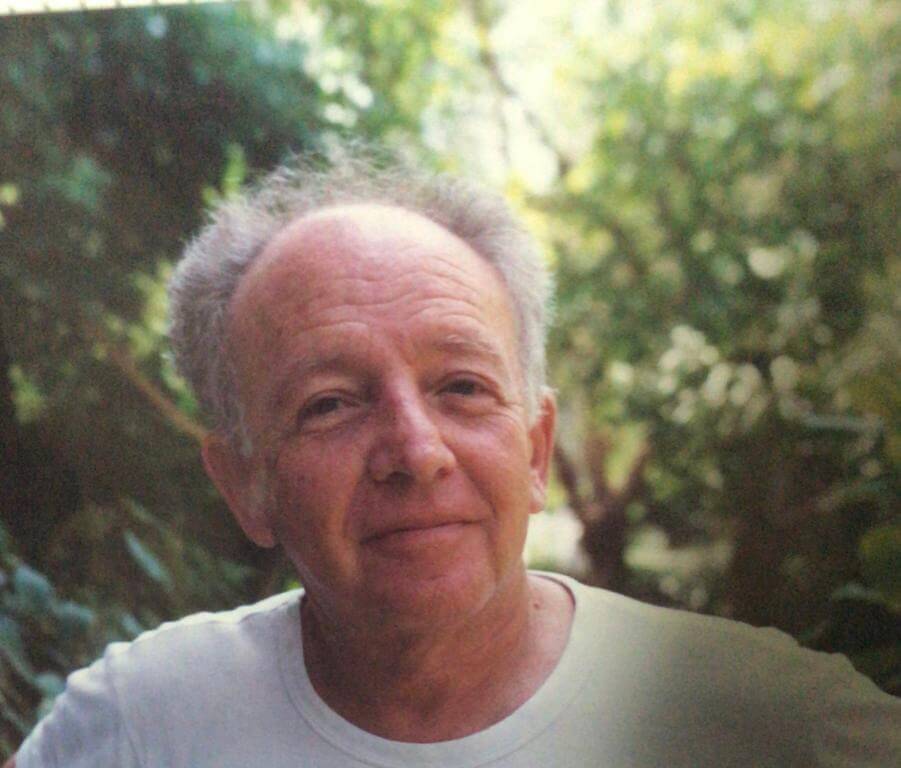

The news of my great-uncle Archie’s death broke on our family WhatsApp group a few weeks back. He was 91 years old, a geochemist for the Weitzman Institute of Science in Israel, and the last living member of a fierce foursome that made up the first generation of my family in the United States on my father’s side.

Archie was the youngest of the four: Betty, the next youngest, was a bookkeeper and died at 70; then Ben — my grandfather — a pharmacist who passed in 2004 at 77; and Harry, the eldest, who was a postman, and died in 1992 at 79. Kaufmans around the country posted a flurry of condolences on WhatsApp, remembering Archie with fondness. The most common refrain was “May his memory be for a blessing.”

I had never thought much about that phrase before, though it is perhaps the most common Jewish response to someone’s death. Now, with the stark reality of a generation gone, I find myself pondering its poignancy.

May his memory be for a blessing. It’s often abbreviated on gravestones as Z”L, for the Hebrew zikhrono or zikhronah livrakha, meaning “of blessed memory.” It dates to the Talmud and is a traditional way of signaling that those who have gone can live on inside of us.

It hints at an afterlife — not in the religious sense of a world to come, but in a real sense of something lingering after death. In some ways, I’ve been living this generation’s afterlife since I moved to New York City in 2017.

My family has a quintessential Jewish New York story. My great-grandfather Israel moved to Lower Manhattan from Russia in August 1913 and became a garment worker. He was followed nine years later by his wife, Stishe, and their eldest son, Harry, who was 12 at the time. The other three were born here. Stishe’s Hebrew name was Channe, as is mine.

Harry stayed in New York the longest, raising two daughters in a Bronx household that he kept strictly kosher. His daughter Fran was my welcome committee when I arrived in the city for college. My grandfather Ben, born the year Stishe arrived in New York — they called him the reunion baby — served in the Navy during World War II and moved out to California in 1965.

Betty, who my father describes as almost comically loving, had two daughters, eventually moving to Las Vegas.

Archie, the baby of the group, took the family history seriously, compiling poetry written by his father for future generations. He moved to Israel in the mid-1960s and had four children, who carry on the tradition of a tight-knit Kaufman clan.

I was at Essex Market recently to get ice cream with a friend and noticed they were serving a special flavor called “L’chaim.” The placard described it as “a celebration of the diverse and resilient people who immigrated to the Lower East Side at the turn of the century, the people who crowded into tenements and started family businesses and brands we are still enjoying today.”

The flavor was dirty chai mixed with coffee, tea and spices from the local Porto Rico coffee company. I ordered it, thinking of Archie’s father, Israel, himself one of these immigrants, hoping he might crack a smile at the poetic longevity of the choices he made so long ago.

Some people say New York isn’t as Jewish as it used to be, but for me its streets are populated by all the ghosts of generations past — their memories blessing the concrete.

The phantom spirit of the garment workers who thoughtfully sewed our culture into the fabric of this city lives on, their bagel shops and bravado serving as defining features of our neighborhoods still.

And so the phrase gives birth to a tangible afterlife. May his memory be for a blessing. May your ancestors walk alongside you, their wisdom becoming your own, and may the many blessings they left weave into your daily life without notice.

L’chaim — to life, or to their lives, perhaps it’s better said. Archie, Betty, Harry, and Ben. Bestowers of the wisecrack and of curls that thicken in the New York humidity, of this city suspended in time, blessed and made mine by their memories, passed from one generation to the next.